By Paweł Mizgalewicz

„This is not a film about Covid”, the director Mihir Fadnavis greeted the audience in Rotterdam. “It's a film about what Covid exposed”.

Such a statement could likely be made about any country – in Netherlands, Covid restrictions led to biggest protests in the country's post-war history, displaying how many people felt general anger at the government and distrust in the central media, even in this relatively peaceful piece of Earth. Now, India is a much larger country, and thus the problems exposed were also on a whole different scale. It's a movie that can make Europeans appreciate the level of life they've been taking for granted. To summarize, the problems might not go against the common stereotype of India seen from the West – there's an extreme amount of poor people there, and their living conditions are extremely difficult. And yet – it's one thing to summarize, and another to experience it. Fadnavis' documentary is one that doesn't waste too much time talking, and instead uses the director's powerful cinematic skills to allow us to live through the humanitarian crisis. “I wanted to make a thriller, like Contagion”, the director says, and the big achievement of “Lords of Lockdown” is that he reached that very goal without cheapening the actual tragic stories of the society in disarray, nor did he soften the film's loud populist voice, calling out the national government's disturbing inaction – both about Covid and about the state of India period.

Lords of Lockdown is screening at International Film Festival Rotterdam

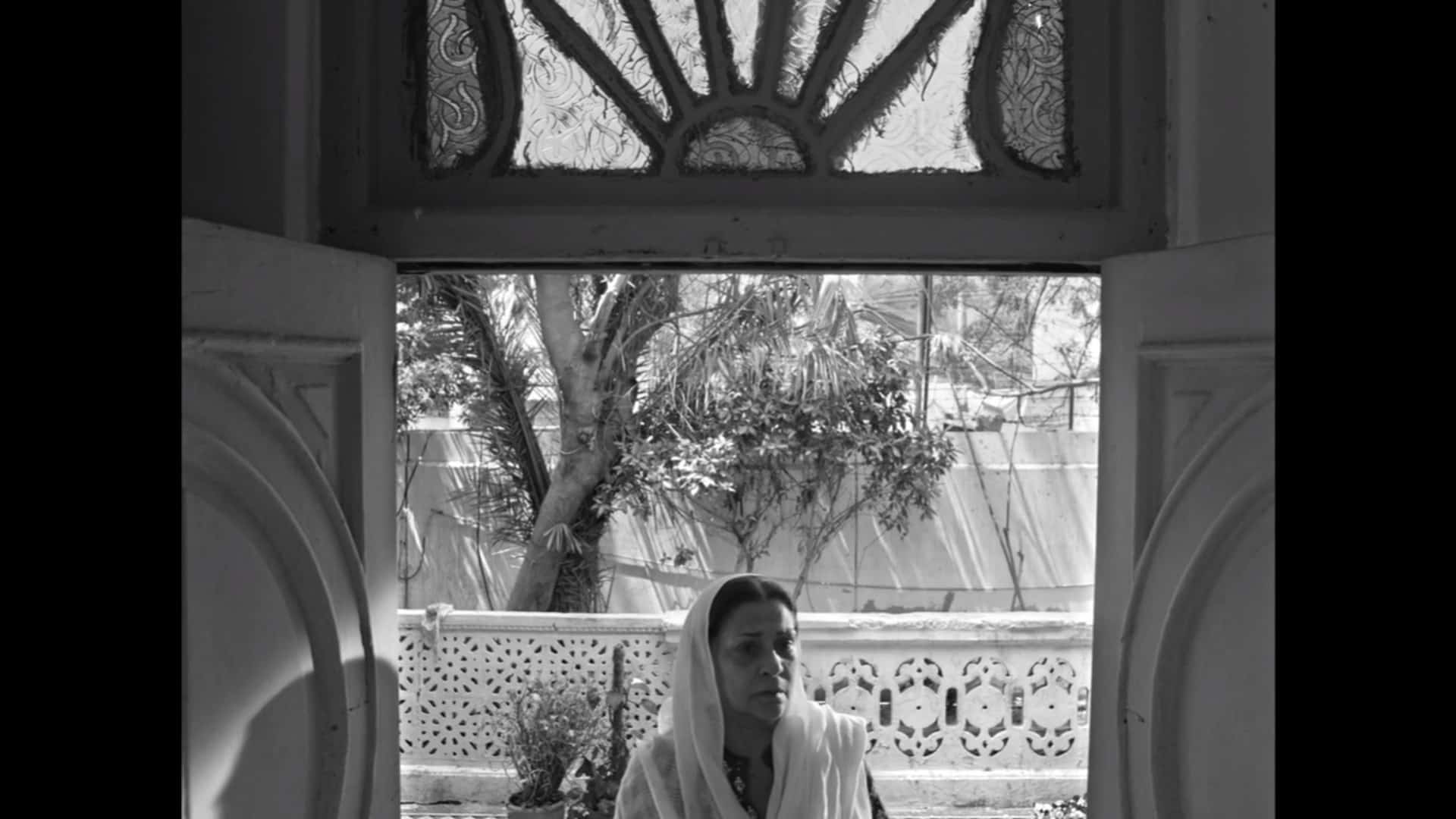

For Fadnavis, a big-scale crisis deserves a big-scale picture, and this is one that is best experienced in a movie theater conditions, impressive and fully immersive despite having been generally shot by a 2-man crew of the director and his DP. Many famous documentary films illuminate an important subject while really making us none the wiser than an ordinary press article would – “Lords…” are not one of those. From the very first to the very last scene, the film strikes us with overwhelming vistas of Mumbai, ones we would expect in an opening of a Western post-apocalyptic superproduction. The streets of Mumbai haunt us with their emptiness, we can almost see the ghosts of the crowds that would naturally fill it day and night. Houses, stores, train stations, beautiful architecture and residential areas, roads and sideways – all locked, all empty. And then the crowds of migrant-worker-filled slums of Dharavi hits us in the face with the sheer amount of human bodies moving on every square meter of the slums, multiple dramas in every part of the frame. If the intensity of those scenes could even recall “Slumdog Millionaire”, the tone and the color do the complete opposite of that. Fadnavis says that he mostly just tried to accurately render what Mumbai actually feels like – “it looks post-apocalyptic even on a good day” – and yet even an experienced cinema-goer can be left in awe of the picture. What is equally imposing to the shots is the color palette – consistently dusty, sun-bleached, washed-off and tired in every scene, it plays a big part in how the film makes us feel. That's the reason why “Lords of Lockdown” are such a strong depiction of an industrial metropolis begging for fresh air to be able to catch a breath.

This is not a film about bleakness and exhaustion, though, on the contrary. It's brimming with powerful characters who really deserve to be called the heroes of the story. They are the focus of the film, the millions suffering being the background to their optimistic, if Sisyphean, struggle. In the center – the Khaana Chahiye organization, an NGO which quickly noticed the growing epidemy of hunger hitting the population of migrant workers. Millions left without a job overnight, with no support and no information of what to possibly expect now – that's a scenario of horror. Khaana Chahiye sees the drama of people starving to death, a fate that concerns them even more than possible infection with Covid. We see them as earnest people of good will, who volunteer and organize effectively to give out massive amount of food to sustain the starving. Those left with no help are noticed, listened to and actively helped by the NGO, hopefully surviving on basis of the rudimentary dishes distributed daily to the crowds. Minor threads of the movie are focused on a female gynecologist organizing medical help for tens of thousands of pregnant women, a renowned journalist organizing a grassroots group of support to the starving, and a railways inspector organizing a safe passage of the migrants trying to flee the country to their homelands. They are all depicted as beautiful people, the ones that make you gain some faith in humanity, as they say – in a work of fiction, we might even feel their characters be made up as a bit too brilliant, but “Lords of Lockdown” documents true acts of selfless charity in such detail that it's easy to just go with the flow and admit: maybe there are angels in this world. That message of belief in the morality of Indian society is the main focus of the film's story.

Rarely, we see captions announce an actual number of people concerned: millions of migrant workers, millions of meals shared. We are both shocked – by the amount of work it must have taken to replicate these actions in such amount, and somehow – not surprised, as the camerawork leaves us in no doubt that while the focal points are limited to a few strong characters, the city of Mumbai alone is filled with stories and people just like those.

In fact, it's a movie that you can understand without the knowledge of any language used, such is the convincing power of the picture, sometimes reminding us of techniques used in advertisements. We don't need words to see what an empty street means and what had happened there. Nor do we need to hear our heroes' words when we see them standing in a circle, talking and gesticulating widely, shirts' sleeves pulled up, with the city panorama in their background and camera swirling – clearly they are inspired men of action, working out some active plan. No commentary is needed when we see them rushing and reaching out to hand out food to the malnourished poor, nor when we see them sitting down and listening to an old lady, with concern on their face. It's a movie of simple heart, determined to send a message that will resonate on every continent.

The documentary's simplicity was not entirely planned by the creators, but the fact is the characters we'd most like to hear have chosen not to speak on the subject at all. The film's narrative about India could be described as one-sided, as the national government is absolutely absent from the whole story. The government's lack of information, effective support or any kind of guidance is only mentioned by all the characters, painting a picture of a depressingly incompetent leadership, universally disliked by the people portrayed. It's an image of a government apparatus that stays silent about the millions suffering, and uses media to divert attention from poverty and hunger to shallow cultural issues. The film chooses not to dwell on those. We can easily imagine the story being made into a commentary on the religious and class conflicts tearing India's culture currently (especially as we spend screen time with Rana Ayyub, a journalist famous for tackling head-on the brutal treatment Indian Muslims are facing), but Fadnavis' crew edited out a film in which the only message about religion is that in face of life-threatening issues, it's not as important. Where the government seems to be creating divisions, the filmmakers seek unity.

Are they perhaps unfair in their critical image of the government? Here we are facing perhaps the most telling fact that I heard from the producer Momita Jaisi after the screening. It turns out that the creators did ask the government for a commentary several times, yet there was no response. In light of revealed facts, it might shock. Especially as Jaisi also underlined that the first audience that got to see the film in India was even more appalled then those in the West. “I had no idea this was happening”, “it opened my eyes to the scale of poverty and hunger” were apparently the common replies. This creates another layer in the film's meaning – if such events can really go unnoticed to the country's middle and upper class, then perhaps we really are in the heart of darkness, and we're just starting to sink in.

The conclusion of “Lords of Lockdown” is thus disturbingly ambiguous. While the film narrative presents us an inspiring tale, some captions and our off-screen knowledge quickly bring a crushing realization that the crisis presented on the screen is not over, and actually hasn't even hit its peak at the time of filming. While the lockdown restrictions have largely been lifted since, and migrant workers came back to Mumbai, they're facing prices enormously inflated in comparison to pre-Covid times. “Hunger is an endemic condition in India”, said the creators during Q&A.“We haven't learned any lesson”.

The European premiere of “Lords of Lockdown” happens to have place just one week after the BBC Documentary “India: The Modi Question” made a splash in the country and abroad, with the authorities working hard on restricting the film's screenings in Indian cities and punishing the ones attempting to air it. “Lords of Lockdown” are not the only film on IFFR 2023 critical about Modi's government – and not even the most accusatory one, which paints a portrait of a country still in fight for a breath of fresh air. “Journalism is being curtailed”, said Fadnavis after the screening, dedicating his film to all the journalists exposing the truth. Maybe the country hasn't “learned the lesson” yet, but we can see that the lessons will not stop coming.