by Paweł Mizgalewicz

Are we but animals? The teachings of Islam would oppose, but any melodrama fan knows that sometimes heart begs to differ. The irresistible allure of nature-calling fuels the new production of the renowned director Sarmad Sultan Khoosat – one that could be crudely described as “Pakistani cinema attempt at Bollywood”, but in fact brings several own spins on both. Let's mention, for example, that the movie kicks off with some gorgeous views of Pakistani nature, our eyes treated to clear azure water amid lush forest, sights that overwhelmed the director himself. “Normally, Pakistan is not too good with maintaining nature…or history… not really”, laughed Khoosat in his passionate Q&A performance, “but here I needed to focus to not become lost in the scenery and not make the story all about it”. The actual focus on the movie is thus another beauty, namely the character of Hina played by the national superstar Saba Qamar. No doubt is left that Hina's a stunner, as in several opening scenes we observe her just laying down poetically, so invariably gorgeous she even goes to sleep in makeup, despite the fact that she lives a solitary and basically male-free life after her husband disappeared mysteriously many years ago.

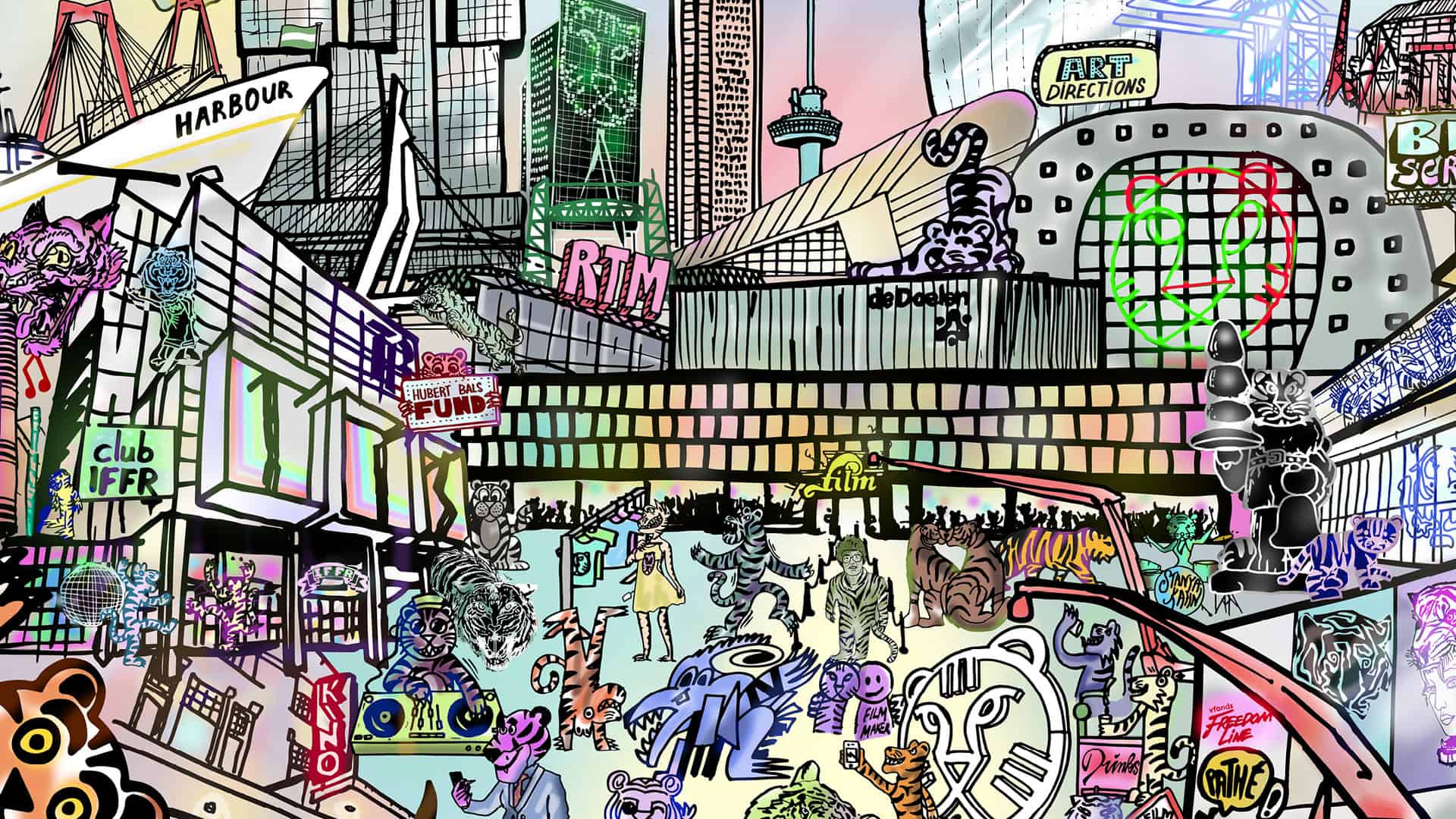

Kamli screened at International Film Festival Rotterdam

The hook is, intentionally, very Bollywoody (“we are big-time consumers of Bollywood in Pakistan”, said Khoosat, “and we tried to attract the audience with these images”) – when Hina starts to drown in a secluded lake in the middle of nowhere, a stranger randomly appears to save her. Strong-armed, with luscious hair and beard, he is one you would love to be saved by. Now, Hina is officially a still married woman, so she tries to act coy and escape her fate, but, obviously – heart begs to differ, and the magnetism on the screen is so in-your-face you might justifiably start kissing the random stranger next to you. For some reason, the handsome Amaltas seems to be living in the forest, presumably to photograph the birds and stuff, and always appears busy with some manly tasks displaying how much he is one with the nature, be it climbing trees, woodwork, or just sitting alone by the fire in the middle of the night. All the more convenient, as Hina is then always able to escape to him and engage in courtship made of deep, vague conversations and meticulously choreographed hare-and-hounds, always with another of the movie's romantic songs as the background and the foreground. Amaltas might, for example, gaze wisely into distance and describe to his lover how he admires a lion for honestly chasing a deer. His lines are straight out of a Harlequin romance; he's the one to ask you: “Shall we elope?”.

As unsubtly as the characters flirt with each other, Kamli flirts with the melodrama cliché, then – a lot of joy to be had with that, along with some traditional pitfalls of, for example, all the climactic dramatic plot threads being actually based on far-fetched acts of characters failing to communicate basic important facts to each other at the moment when it would be obvious. Not that it matters much, in the end, in a movie as focused on emotions as this. Follow them, too, and you will find what makes Kamli such a thrilling watch in the end, with the melodrama tools not only used, but also played with, just enough to give us a profound cinematic experience to have a crush on.

As Robert Altman would like it, 3 Women are in the center of it, all of them another dimension of the same experience, with the central motive of the movie being cases of a disappearing man. Like all the characters of Kamli, the women can't get over how beautiful Hina is, obviously. The aging paintress portrayed by Nimra Bucha uses Hina as a model, and stares at her like a hungry dog, longing like a vampire for the youth, beauty and virility that she embodies, seemingly both in love and in hate with her. The paintress' husband looms around as a scary presence – a suit-wearing, English-speaking, detached silver fox that seems to shame the wife's aging purely by his existence. When one of the models gifts the paintress fertility medication, we can already laugh – just by the way she reacts when the husband enters the room we know all too well that this is not a couple that's slept together anytime recently. Perhaps the husband creeps at the younger Hina, too – not that we really see that, but that's what the women assume. He's a man, after all. The third main character is Hina's sister-in-law, who is blind, and yet, in her own way, just as obsessed with image. Despite passing years, she's still wallowing in sorrow after her brother's disappearance, her vision of spirituality all based on strict religious orthodoxy and a sense of vanitas guiding her to regard all the physical needs as shallow and immoral. “It is all the fault of your body”, she decries the indecency happening around Hina.

The scenes between the three are genuinely exciting to watch, flirting with violence in various ways and brimming with kinetic energy just as the romantic dances do, all bringing some interesting untold perspectives on the positions of power in the moment and various kinds of yearnings that humans might feel. Crucially, they are very well-acted – sure, Qamar's dreamy doe eyes or Bucha's sour stare are maybe more intense than needed, but when all is said and done and we learn of every character's place in the whole plot, it fits the film well that the characters here are presented as larger-than-life stereotype. It's not only about making the dance scenes fresh and fun, but the camera's eye for the spectacle belies the movie's compact, two-people-talking scene setting in most of the scenes. By and large, the director succeeds in his goal and it's not the scenery but the people that are the most eye-catching in “Kamli”.

How much of this mixture of a musical romance and more complex psychological tale will speak to you – that's up to your taste, but the film proves that Khoosat is an impressively skilled and versatile director, one that we are lucky to welcome back in the wider festival circle after his previous film “Circus of Life” was accused of blasphemy in Pakistan and banned from the cinemas. Here, the director combines spiciness and humbleness in a way that just allowed him to sneak past the censors while still delivering a show provocative in several ways. It's also Khoosat's coup to have directed such a convincing female-centered film, although that's been achieved with a big support of women engaged in creating “Kamli”, from the creator of the original story to the actresses and the crew.

During the QA, Khoosat stressed out that he tried not to impose his personal perspective on the women's story and to respect the original material, while also using all the experience of women around him in his family and work to stay true to the story's core strength. It worked out, and “Kamli” still feels mostly like a film by women, about women, for women. “You're one of us now”, said Bucha to the director at the stage.