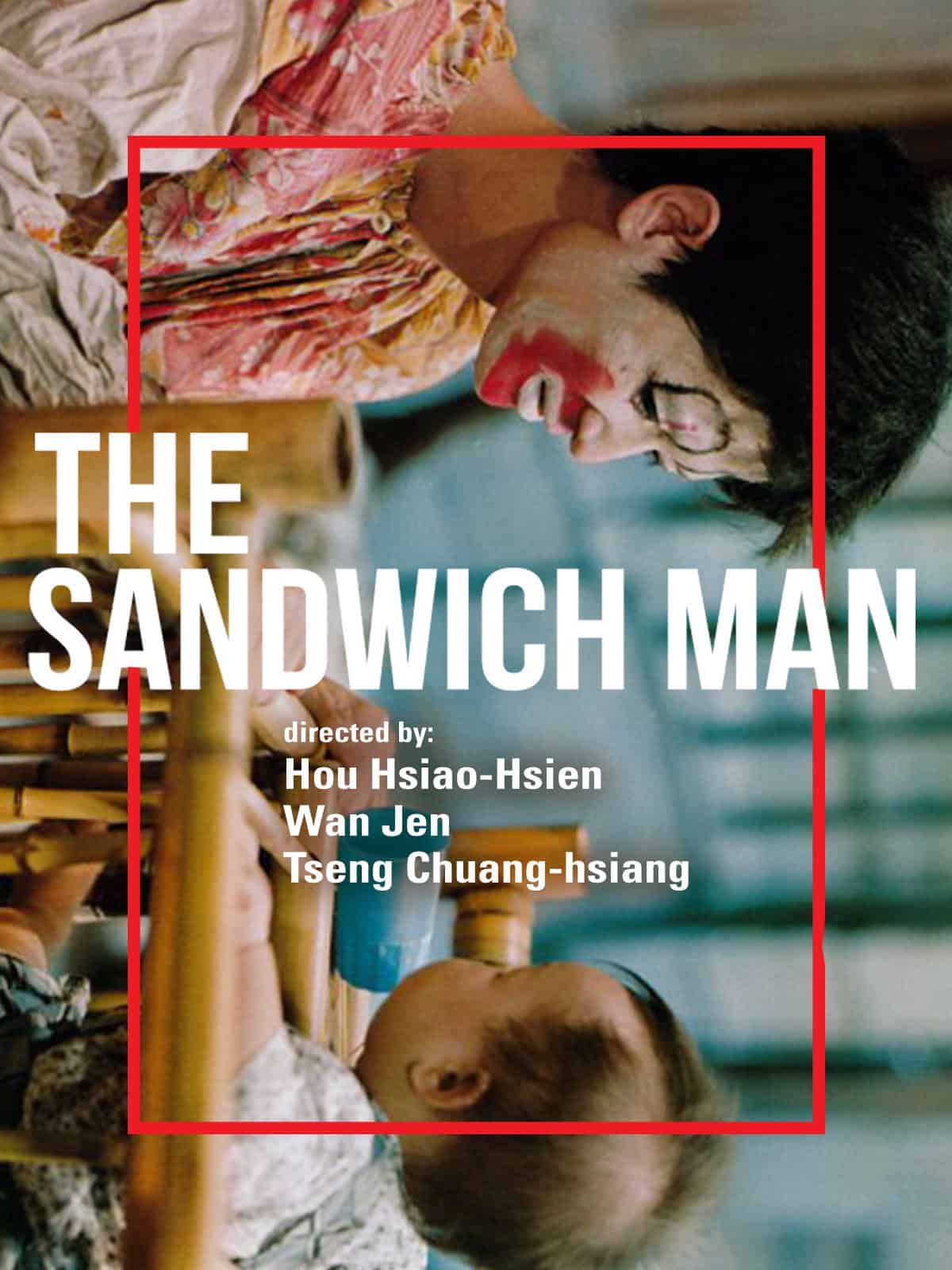

Considered one of the most distinct samples of Taiwanese New Cinema, “The Sandwich Man” is an omnibus of three short films based on stories by Huang Chunming, which deal with the working class in Taiwan during the 60s.

Buy This Title

on Amazon by clicking on the image below

The first segment, titled “The Sandwich Man” (alternatively “The Son's Big Doll”) is directed by Hou Hsiao-hsien and takes place during 1962. Kun Shu is an illiterate young man who works as a “sandwich man”, wearing clown make up, and advertising billboards back and forth and roaming the streets, in order to provide for his wife and child, while she is waiting for a second one, which is what led him to take up the particular job in the first place. Kun Shu is frequently ridiculed, pranked, his father repeatedly tells him that he is ashamed of him, while his boss treats him as a necessary evil. Having no one “under him” in the social hierarchy, he frequently channels his anger towards his wife, the only person he can actually bully. The true irony, however, comes from his baby son, who seems to only recognize him when he is painted as a sandwich man.

Hou makes a direct comment about the impact of progress on people such as the protagonist, who were not equipped to follow it, thus barely making a living, essentially in disgrace. That Kun Shu begs the owner of a theater to, essentially, be a clown in order to support his family is indicative of his situation. There is a sense of tragic humor and irony permeating the whole segment, which is cemented in the aforementioned last part. At the same time, that in the end, the family survives and even have kids, does come across as an optimistic message, in an otherwise quite dramatic and pessimistic story, which does echo, though, as rather realistic and indicative of the times. Chen Bozheng, who plays, Kun Shu, gives the most memorable performance in the whole film.

The complicated and minimalistic structure and the flashbacks that are not presented in chronological order are some of the elements that would later characterize Hou's style, and were initially used in this particular film. The movie is considered one of the most distinct samples of New Cinema, and was his first work that was screened outside Taiwan, specifically in Japan

The second segment is directed by Tseng Chuang-hsiang and is titled “Vicki's Hat”. The story takes place in 1964 and revolves around two salesmen who are trying to sell imported Japanese pressure cookers to the villagers of Bu-dai in Jia-yi, a fishing village in central Taiwan. Despite the fact that the appliance is obviously dangerous, the two keep at it as their sole source of income, for their own reasons. 30-year-old Lin Zai-fa in order to raise money to support himself and his pregnant wife, and 20-year-old Wang Wuxiong in order to get away from his home and find a wife, after being dismissed from the army. The latter eventually also starts exhibiting an attraction towards Vicki, an elementary school girl who passes from the house they rented and always has her school hat on.

The accusation towards the Japanese penetration in Taiwanese society, which is presented here through the whole pressure cooker concept, is as evident as possible, with the drama that eventually ensues being quite harsh in that fashion. Again, the extremes the members of the lower working class had to reach in order to make a living is highlighted throughout, not just through the particular type of selling, but also for the way they had to live during their “excursions” in the country. The act of defiance during the end cements this approach in the most eloquent and also cinematic way. The ‘romance' with the elementary school girl is as intriguing as it is unusual in its presentation for the time, but is also quite disconnected from the main narrative, and perhaps it should be interpreted as a metaphor for the corruption of the new generation.

The third is directed by Wan Jen and is titled “The Taste of Apple”. It takes place in 1969 and concerns the story of Jiang Afa, a poor day laborer who is the father of five children, one of which a mentally handicapped girl. When he is hit by a car driven by Colonel Gray, an officer of the U.S. Marine Corps stationed in Taiwan, he ends up with broken legs and having to stay in the US Naval Hospital for months in order to recuperate. Inevitably, his whole family eventually moves into the hospital.

Evidently, the most humorous segment of all, Wan Jen's part follows an episodic narrative, which aims at highlighting the impact of Westernization and the difference between Asians and westerners. The episode with the toilette is indicative and definitely the most hilarious in the whole omnibus. Although the approach is comedic, the ending comment is actually quite harsh, as indicated by Colonel's Gray attitude throughout the story. Initially we seen him stupefied by how inorganized and poor Taiwan is, which leads him in the end, to take the role of the benefactor, giving a significant amount of money to the family as compensation. The irony, however, is that before doing so, he almost killed the man with his speeding car, with the message here, although subtle, being quite clear and pointed.

Despite the differences in cinematic quality, which actually deteriorates as the segments progress, the context through the three parts of “The Sandwich Man” is rather rich and quite smart in its presentation. The three filmmakers induce their films with irony, humor and drama in order to present their comments, occasionally through metaphor, while still entertaining their audiences. At the same time, the blights of urbanization and westernization (and Japanisation) as much as the rather bleak financial circumstances the country experienced at the time, along with the lack of technological progress, are highlighted quite eloquently, on par with the general style of Taiwan New Cinema, which focused on the realistic depiction of the lives of common people.