Combining the horrific with the grotesque and the sensual in order to both entertain and to present various comments in extreme fashion has always been one of the knacks of Japanese cinema, with filmmakers like Takashi Miike, Sion Sono and Tetsuya Mariko among others having thrived in this approach repeatedly. Noboru Iguchi proves that he is also a member of the “group”, with his latest work “Tales of Bliss and Heresy” an omnibus of three different parts.

“Tales of Bliss and Heresy” review is part of the Submit Your Film Initiative

The first one is titled “Painful Shadows” and focuses on the interactions between two office workers, a man and a woman, with the former being the higher up. His behavior, however, is creepy to say the least, since he peeks on his colleague, makes snide comments about her writing, and even teases her regarding food. It turns out, though, that the girl has a secret ally in the face of a plumb ghost, and the tables are soon turned, as the foot scene eloquently highlights.

The hardships women have to face in the working environment take a rather extreme turn here, with the way the upper hand changes being one of the most intriguing aspects of the segment. Furthemore, the combination of horror and sensualism, as in the depiction of the girl's legs, the perverse voyeurism and the crime and punishment aspect works excellently here, in a part that is as intriguing as it is economical, as the almost complete lack of dialogue showcases.

Kohei Matsubara's cinematography, along with Yasuhiko Fukuda's music add intensely to the sense of creepiness, while the presentation of the ghost is exceptional. The acting is also on a high level, with both actors exhibiting impressive transformations, while Airi Yamamoto's expressions in the role of the woman are truly exceptional and Daisuke Ono is quite convincing in the role of the creepy boss.

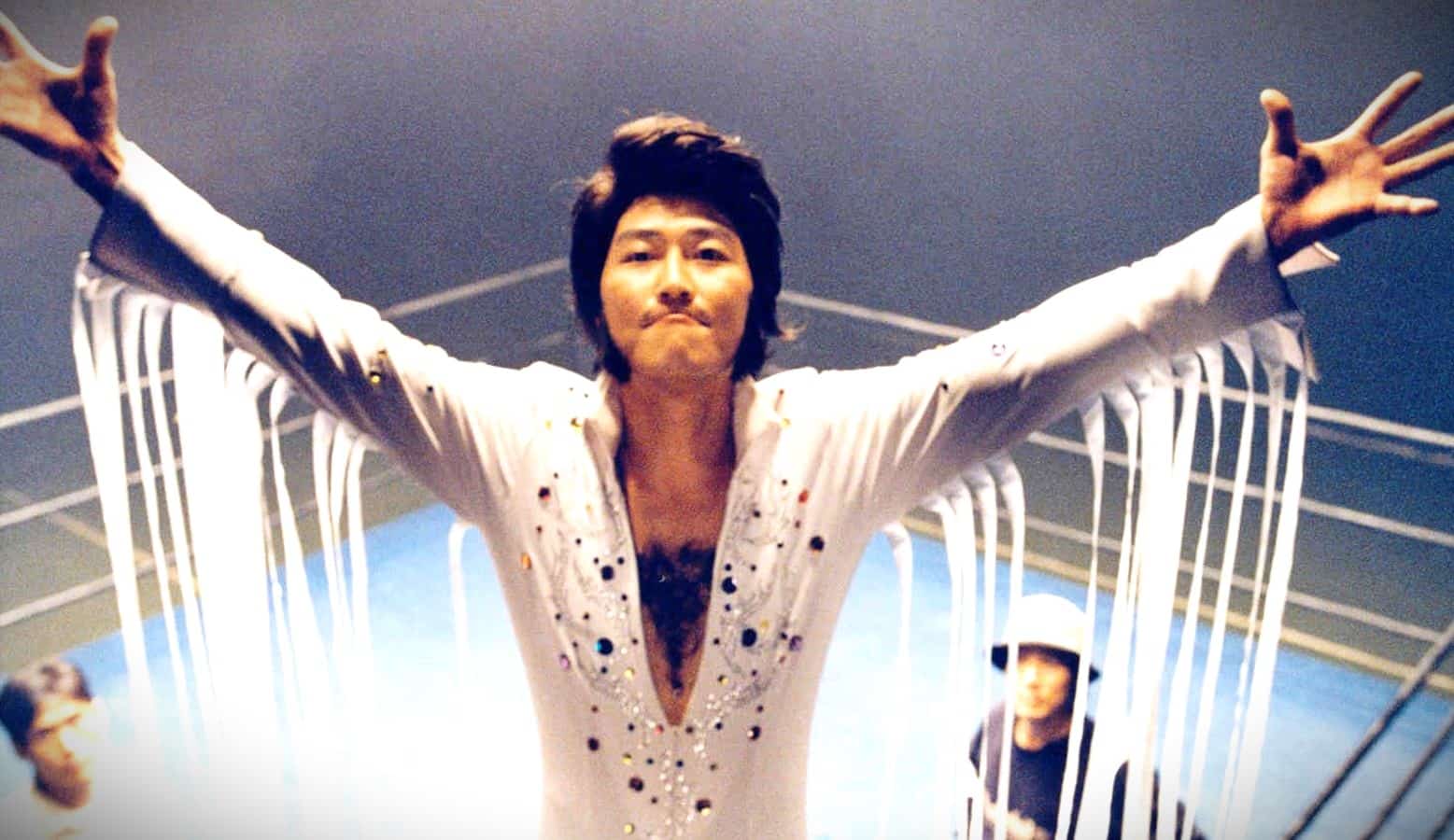

The second story, titled “The One Armed Flower” revolves around Yusuke, a timid, junior highschool boy, who is being bullied by two delinquent girls from his school, who even threaten to hurt his beloved older sister, with whom he lives with. His meeting with a woman with a mutilated left hand changes his perspective and overall demeanor completely, but the presence of his sister's boyfriend complicates things even more.

Moving somewhere between the nightmare, the dream and reality, the segment focuses on the concept of bullying, and how the lack or presence of parents can shape youth. At the same time, the notes of fetishization and perverse sensualism revolving around sadomasochistic tendencies are among the most intriguing aspects here, along with the role reversal of a boy being bullied by girls.

Minase Yashiro gives a great performance in the role of the mysterious woman, while Keita Okada is quite convincing as the victim. The cinematography here finds its apogee in the various exploitation scenes, which are also the most entertaining aspect of the part.

The last part, titled “The Table of Bataille” (Iguchi also showed his love for the French author in “The Flowers of Evil”) moves into more “disgusting” territory. Tsuyoshi is an androgynous-looking young man who feels guilty about eating and going to the bathroom due to a childhood trauma. He has found some solace in photography, and it is this hobby that allows him to begin interacting with Tamako, a waitress at a coffee shop, whom, to his surprise eventually even invites him to dinner. She, however, is revealed to have an even bigger trauma having to do with her defecating. The two are soon connected through their traumas, but their relationship takes an even more perverse turn eventually.

One could say that Iguchi goes somewhat too far in this segment, with a number of scatological elements being occasionally quite difficult to watch. At the same time, though, the main comment of all the film actually, of how love can be found even in relationships that the world deems perverse, finds its apogee here, while the concepts of shame and alienation conclude the rich context of the segment.

Kokonoha Benio as Tsuyoshi and Nakamura Arisa as Tamako give nice performances here, with their chemistry being among the best parts of the part.

The two main themes of the omnibus emerge as quite interesting, with Iguchi focusing on a type of love that is characterized by utter sincerity and the revealing of all those secrets everyone of us fosters. His comment comes through excessiveness, but in the end, if one looks beyond the extreme elements here, the comment is as clear as it is thought provoking. On a second level, and also equally interestingly, Iguchi focuses on a body part for each segment, with the first dealing with legs, the second with hands, and the last with butts, in an element that is quite smart and also works quite well in terms of visuals.

“Tales of Bliss and Heresy” is not a film for everyone, and the truth is that particularly the last part is not exactly for the faint-hearted. Underneath the extremity, however, lies a rather rich context and a number of very interesting comments, that show that extreme cinema can also be implemented in such a way, in a trait that is both of Iguchi himself and Japanese cinema as a whole.