Graduating as Ozu's assistant with his debut feature-length at Shochiku in 1960, Masahiro Shinoda (b. 1931) saw the dawn of the Japanese New Wave and rose to prominence alongside the likes of Nagisa Oshima, Yasuzo Masumura, Koreyoshi Kurahara, and Shohei Imamura among a whole host of others. Though he would spend most of his career reinterpreting and reimagining whole genres including the yakuza film and jidaigeki, the films across his four-decade-long career would predominantly be united by a re-examination of Japanese historical, societal, and national identity, complete with a focus on alienation, mythologies, and religious and moral turmoil. Frequently coupled with composer Toru Takemitsu, cinematographers Masao Kosugi and Tatsuo Suzuki, and actress Shima Iwashita (whom he would go on to marry), Shinoda's films grapple with man's perturbing darkness and its effect on the personal and national conscience. Like most of his Nūberu Bāgu compatriots, Shinoda frequently negated cinematic and narrative traditions, and instead toyed and played with aestheticism, style, sound, and folklore to bring his visions to life.

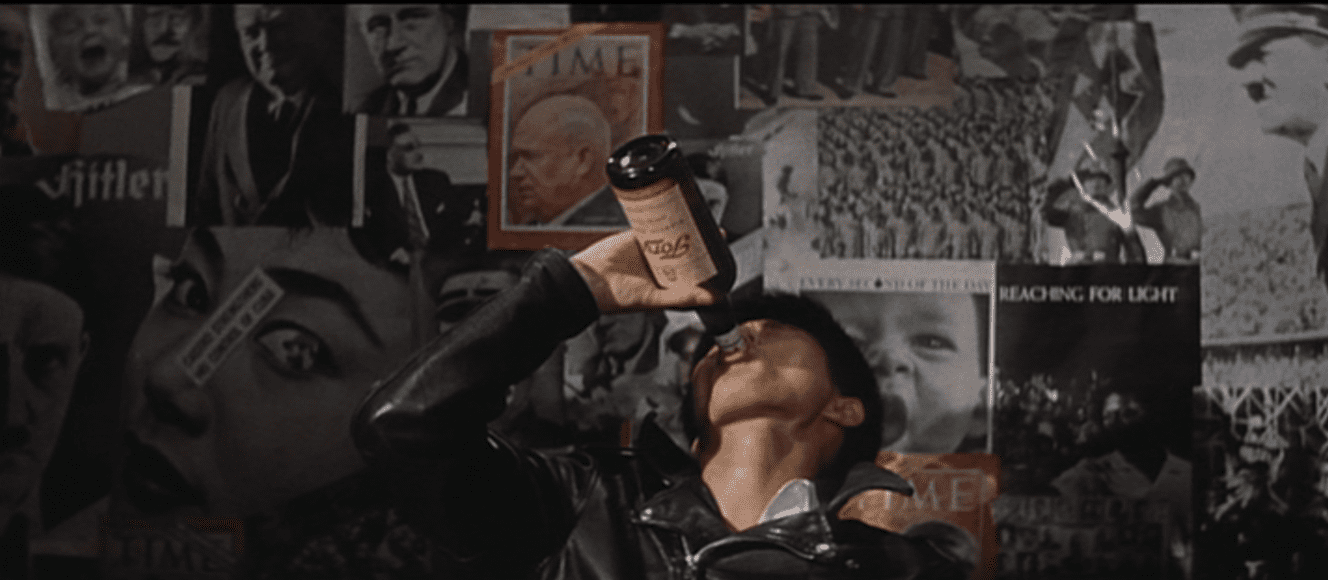

1. Youth in Fury (1960)

A rambunctious furor of hedonistic violence with its finger on a hair trigger, Shinoda's second feature of 1960 is as ingrained in the national sentiment at the time as much as it is in the rebellious taiyozoku subculture. With its anger pointed at a State it deems defeated, corrupt officials, and alienation, “Youth In Fury” is armed to the teeth with pulsating jazz and a nihilistic attitude at a constant boiling point. Frequently twinned with Oshima's “Cruel Story of Youth”, Shinoda lays the foundation not just for his avant-garde trajectory into the Nūberu Bāgu but also his relationship with Takemitsu and Iwashita, as well as cementing the already-established twinning with Kosugi.

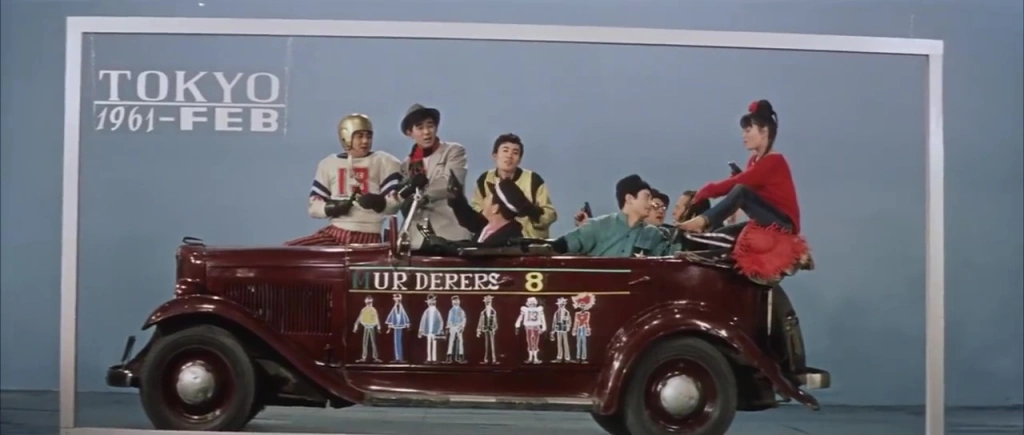

2. Killers on Parade (1961)

Returning the following year with a picture so tonally opposite from “Youth in Fury” it verges on the inconceivable, Shinoda and writer/poet Shuji Terayama strike satirical gold with their musical caper centered on a group of hired guns tasked to kill Shima Iwashita's Arisaka, secretary to a trade paper bent on bringing down the Mizuta Construction Company, until Yusuke Kawazu's cocky yet charming Ishida is given the job. Though its aloof, camp style pops with vibrancy, the film doesn't shy away from the shadiness of its no-gooders, brushing its villainy cartoonish only elevates the heinousness of corruption out of the shadows; this leaves “Killers on Parade” an off-kilter romp whose playfulness Shinoda (and editor Yoshi Sugihara) would continue to hone.

3. Pale Flower (1964)

Masahiro Shinoda directs a title that thrives on one of the most impressive noir atmospheres ever to be presented on film. To achieve this level, Shinoda implements all kinds of cinematic aspects, particularly during the gambling scenes, which emerge as the most impressive in the movie. The Ozu-esque visual approach (Shinoda worked as his assistant after all) is enriched with a number of panoramic shots and an approach towards the introductions of each character through the view of the rest of the people on each scene, which works wonders for their individual sketching. Particularly the ways the protagonists are made to stand out, and especially Saeko's difference from the rest of the “inhabitants” are highlighted in the most impressive fashion, in a testament to Masao Kosugi's work in the cinematography, which also thrives on his distinctly noir use of shadows. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

4. Assassination (1964)

Tales and myth are abound, circling Tetsuro Tamba's Hachiro Kiyakawa, a masterless samurai with questionable allegiances at a time of the nation's greatest upheaval in over three centuries. But which ones are to be believed? Employing the trickeries “Rashomon” so masterfully executed, Shinoda's debut jidaigeki is as far removed from the heroic ideals portrayed in the genre as one could get. Instead, “Assassination” fixates on instability – of narrative and truth – in its teetering role in historical remembrance. Here, Kosugi beautifully enshrines light and shadow as principal components in this brooding and iconoclastic reexamination of the Japanese story.

5. Captive's Island (1966)

The sound of cracking whips is as striking as the lashing waves and deafening silence of memories in Shinoda's tense yet concise revenge flick, his first independent feature after leaving Shochiku. This raw, strikingly brutal tale of a man hellbent on striking vengeance on his reform school torturer is as layered with deception as any other film in the director's entire filmography; what it lacks in exuberance, “Captive's Island” makes up for in its intricate storytelling as well as Shinoda's and cinematographer Tatsuo Suzuki's knack for rendering an island of pristine beauty a nightmarish domain where traumatic memories have taken up permanent residence.

6. Double Suicide (1969)

Shinoda's exploration of free will, love, lust, and death is a tragic tale, a sad downward spiral towards an inevitable conclusion where false hope occasionally pops up only to be knocked down immediately by a cruel twist of fate. “Double Suicide” mercilessly builds up towards the tragic titular shinju while the characters struggle in vain to avert the grim end the universe has written out for them. It's a fantastic retelling of the old story and displays Shinoda's ability to balance avant-garde impulses with more traditional storytelling. Captivating, sorrowful and surely even more rewarding upon multiple viewings. (Fred Barrett)

Buy This Title

on Amazon

7. The Petrified Forest (1973)

While “Youth in Fury” showcased for nihilism at the start of his career, “The Petrified Forest” finds Shinoda at his most abyssal, a film riddled with claustrophobic paranoia and a discombobulating score from long-time collaborator Takemitsu. A glimpse at the bleak state of the nation which its director envisioned, this take on the Shintaro Ishihara novel in which a med student becomes embroiled in a poisonous affair with an old friend, a beautician, after they murder her boss – as well as the barbed relationship with his mother – is a disturbing, almost soul-destroying experience. Never one to skirt the dark underbelly of humanity, Shinoda drags both his leads and his audience through this quagmire of desperation and leaves none unscathed, completing what he set out to achieve with 1971's adaptation of Silence

8. Himiko (1974)

Within the triumvirate of “Pale Flower”, “Double Suicide”, and “Himiko” – oft-cited as Shinoda's greatest accomplishments – it is no doubt the latter which deftly defies explanation. Cinema and theatre disassembled and reconstructed seemingly multiple times over, 1974's “Himiko” is the very definition of sensory bamboozlement akin to Jodorowsky's “The Holy Mountain”; exploring and unpacking its taboos of forbidden love and Machiavellism within a meticulously grandiose yet paradoxically minimalist stage design, this intoxicating reimagining of the shaman queen is at once psychedelic and ethereal. A deluge of prophetic shrieks, primordial howls, and stupefying visuals, this is Shinoda at his most experimental and, more importantly, transcendental.

9. Under the Blossoming Cherry Trees (1975)

There is nothing but sly cunning in Iwashita's smile as she demands Tomisaburo Wakayama's Mountain Man carry her up to his home then kill his many ex-wives after he's killed her husband claiming her for himself, betwixt by her beauty. What follows can be best described as a Sisyphean nightmare: an absurdist monotonous hell becoming increasingly more deranged the longer “Under the Blossoming Cherry Trees” continues. Unhinged and bloodthirsty, both Shinoda and Iwashita are at play here, albeit a cruel, sadistic pleasure at the expense of both its lead and audience. It is debauched for sure, but a fine example of how Shinoda continued to metaphorically flip his own script several times over.

10. Ballad of Orin (1977)

Shinoda's Japan has always been at odds with itself – one in a constant state of flux and re-examination (at times verging flippantly towards the postmodern) – and its character frequently brought into question. In his penultimate film from the 1970s, the luring spectre of modernisation lingers in the periphery, daringly, whilst its titular goze is tossed around both by men and the relentless march of progress and empire. Imbued by one of Iwashita's most complex performances, Orin's loneliness is fraught with harrowing, wretched inevitability, one which too many women have known all too well. Exemplifying the vulnerability of women and social outcasts through the country's imperishable history, “Ballad of Orin” can be tough to stomach but is pure, forlorn poetry in motion.