If you're a cinephile in Singapore, you've probably heard of Mark Chua and Lam Li Shuen. Also known as Emoumie, the artist-musician-filmmaker duo have a widespread practice that mixes all of the above. Their groovy features, “Revolution Launderette” and “Cannonball” and surreal shorts “The Cup” and “A Man Trembles” have all been screened internationally, including at BFI London Film Festival, Singapore International Film Festival (SGIFF) and Asian Film Festival Barcelona (AFFB). Their newest short “Chomp it!” enjoyed a recent world premiere at the International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR).

From steampunk coffee-making humanoids to carnivorous washing machines, Chua's and Lam's imaginative tales may be best described as distressfully exciting, told from little sunny Singapore. Wanting to know more, we sat down over coffee and chatted about the duo's works, what inspired their unique style, the challenges of creating local cinema, and more.

“Chomp It!” screened at International Film Festival Rotterdam

To start, tell me more about your new film “Chomp it!”

Li Shuen (LS): Mainly, the film came out of our desire to express the sense of fatalism under the skin of Singapore life.

Mark (MC): And we got this bizarre idea of crocodilian men in a swimming pool.

LS: To us it was a way to express what the Singaporean way feels like. To both laugh, but also cry at the cruelly funny nature of that Singaporean way. Thinking about that, and visualizing it as a state of relations that, for us, is very much based on things like utility and value. Even surviving it makes one as absurd as the rest. That's what was going through our minds when we were making the film.

In your previous shorts: “A Man Trembles”, “The Cup”, and perhaps also “Chomp it!”, I and many others have enjoyed your joint surreal, otherworldly take on everyday life. How did that arise between the two of you?

MC: I think with every film, we're trying to look under the surface of life in Singapore. Try to look at our madness, our desires, our drives.

LS: To us, what that looks like on screen is something very curious and fantastic. Thinking about histories of places, the kind of languages we speak, that surrounds us. The spiritual, and also the existential reflections that can be teased out between all of this. That's what brought us to absurdist imagery, and more humoristic leaning perspectives.

At the same time, something (Mark and I) always talk about is this idea of the human animal. Looking at the human animal, but with some courage.

MC: Or making the films sort of, gives us courage to look at the human animal. That's why (the films) all come out like that.

Courtesy of Emoumie Pictures.

I'm curious. Why crocodiles? We hardly see them in Singapore, except for the one or two mysterious sightings.

MC: That's the thing. Actually, it's one of our native animals, this estuarine crocodile. Like the saltwater crocodile. We felt it was the perfect image to encapsulate that kind of… state of relation between each other. Because sometimes, we are out there in the city, and everyone's a bit cold-blooded to each other. A bit like mercenaries.

Were there any inspirations?

LS: Maybe for us, inspiration is more about looking at place, history and the times and conditions. That's generally where we like to dive in.

MC: But just taking it with a bit of humor as well. I think that's where this started.

LS: Yes, for example with “A Man Trembles” it was looking at Sentosa. The history of that land, and some of the conflicts in that history. It's mainly what we're drawn to, and what we try to explore more.

With that, how would you two define your own internal experiences of being Singaporean?

MC: It's something we feel really needs to be unpacked, because we want to understand our nightmares, and our fantasies more. But overall, the experience has been rather absurd and fun at the same time. Which is something we want to make more sense of as we go along. I think there's still so many films, not just from us but in Singapore. There are still so many films to make.

LS: For us, each film is our effort to peel back the layers. Another thing quite important to us is trying to think beyond some generalized, prescribed ideas of what Singapore is, or what Singapore is accepted to be. Out in the world, today.

I think we've come far enough that in our films, we don't need to mask how we speak, or play to Asian values. We don't need to play the foreign language card. That's something quite exciting for us. To show the rest of the world what we (Singapore) are about, and not what the world wants to see of us.

You two might have already answered this question, but do you think local filmmakers are still heavily concerned with unpacking our national identity? Do you think this concern will ever fade away?

LS: The unpacking is always an evolving thing. Evolving to our times, and conditions that's always changing. I think that's why it's a never ending effort.

MC: The different forms that this representation can take is very exciting for us.

LS: When we're representing Singapore onscreen, sometimes there's this idea of what the world understands about Singapore, or what the world expects to understand of Singapore. So it's exciting for us that as we're moving forward, we are starting more and more to…

MS: Say it how we want to say it. Maybe there's something quite radical with pushing that out. And together with other filmmakers here too.

Congratulations on “Chomp it!”'s recent premiere at Rotterdam 2023! How was the festival experience there? Was it what you expected?

LS: It was more than our expectations, especially in terms of the (audience) reception. The audience was having very different reactions, very good reactions. The DP/cinematographer Lincoln Yeo was also in Rotterdam with us, he was very happy because people were saying that they could see the humidity in the image. Because he had to handle that mechanical Bolex for the whole process of filming. So we're very happy with the way people responded to the images, and the idea of the Singaporean madness in the film.

MC: We also met a lot of other Asian filmmakers, Southeast Asian filmmakers. We already knew each other but we finally got to meet and hang out with Burmese filmmaker Lin Htet Aung.

LS: We actually had a chance to do a radio show with him at this art space called WORM. We presented Southeast Asian and East Asian music, mostly by our friends that we met through making films. During the show we did a live sound and poetry piece with Lin Htet. That was really nice for us.

Did you two manage to see the other Singaporean films at IFFR 2023?

LS: We saw the Rajendra Gour programme, and we met most of the Singaporean filmmakers.

MC: All the films were quite totally different from each other. So it was quite a broad range, and all the responses were actually quite good. Different perspectives of Singapore, where we're all from. No matter what time of day the screenings were on, all of them were very… Actually quite a few of them were sold out. Ours as well. There were like 3 screenings sold out. It's an interesting experience to see that receptivity to these different styles, that are all from the same region.

It's surprising to see such a huge landscape, with Boi Kwong's “Geylang”, your “Chomp it!” and Charlotte Hong's “SMRT Piece”…

MC: And these restoration pieces from so long ago.

LS: So it's over different time periods, and through many different lenses. It was nice because any other country's film culture has such a diversity, and I guess they also have to think about regionalism. But we don't really have this question of regional cinema. I think that diversity comes out in other ways for us.

There have been many Singaporean films, and perhaps by extension, many Singapores. What do you think the general constructed Singapore looks like? But also, what does your Singapore look like?

MC: I think we are always quite obsessed with, like what we discussed a little just now, how we go mad. What we are driven by, what those feelings and drives look like. It doesn't quite look the way we see things as we walk around, that it's something that other Singaporeans also attest to when they see it… It's really bizarre. There's some kind of subconscious layer of our life, right?

But on the other hand, there are these different ‘stock' versions that we find, that are more concerned with things like getting a paycheck for validating a certain version of what things are, and in that sense we are very drawn to the mode of independent, more DIY ways. Where you're actually more irresponsible. And by doing so, we almost feel like that irresponsibility is actually necessary to finding a sense of things that feel right. Or feel like it captures that layer of Singapore we are getting at.

An irresponsibility to…

MC: Okay it sounds weird but, irresponsibility to our society. Feels like we can find how our society feels.

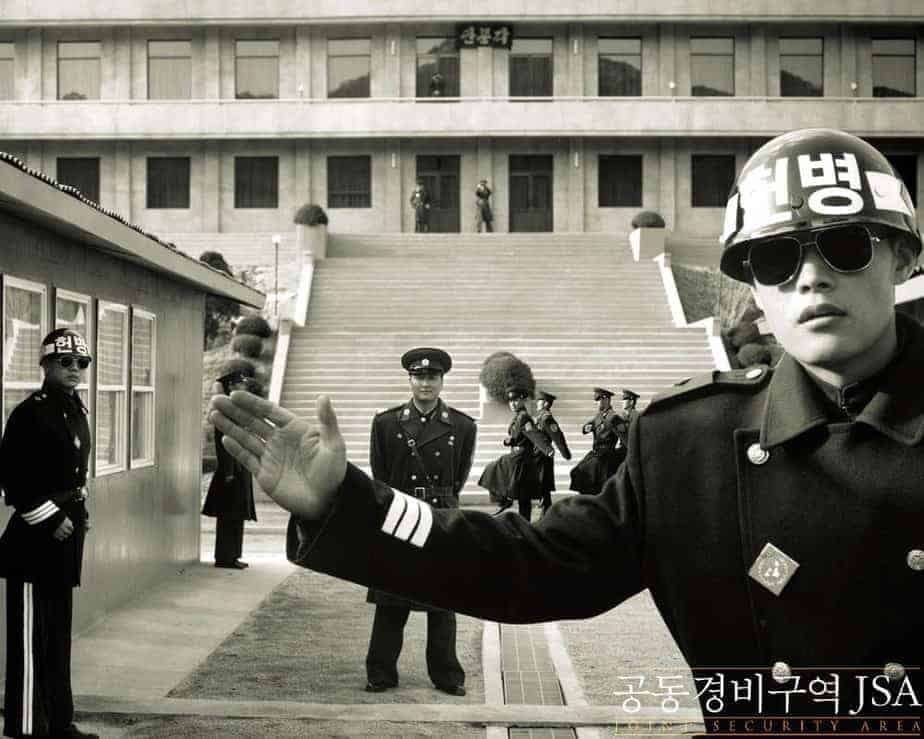

Courtesy of Emoumie Pictures.

How have non-Singaporean audiences reacted to your films so far? Does it go against their ideas of Singapore?

LS: I think most of the time it goes against. And one important aspect is the language. A lot of people are very surprised at the way that Singaporeans use language. Whether using Singlish, or a mix of languages. But just not that perfect idea of what a piece of ‘world cinema' should be.

MC: Based on their preconceived notions, I think they get a bit shocked. Like “Oh my God, why are you projecting this messed up English?” But that's just like… how I speak. I think in some places, they might be like “Please stop speaking your broken English.”

LS: They see it as broken. Even after learning the culture or context, maybe they feel that the broken English is not beautiful. It's something we find curious and interesting to prod and provoke, the more we find such responses.

MC: Yes, but there's also good responses. Some places we've been to, they get to find out more about where we're coming from, what we're thinking about. And sometimes there are… similarities?

LS: Like commonalities. And that's also something we cherish very much. Because having this collective experience in cinema is quite powerful.

Everytime there's a discussion about Singaporean film, language comes into the picture. It's so unavoidable: How do you want to speak English? How do you want it to sound? How has this affected both your script writing processes?

MC: In a weird way, we just always have to keep in mind to ignore it, and put it out as it is, write it how we want to write. Because of all this discussion, there is always this layer that the Singaporean filmmaker thinks about: Should I render this through a different, more foreign sounding language, so it can help me be more understood or something.

LS: That's just one of the issues of smaller countries, or younger film culture. We are always looking outside, and looking inside and it's always that negotiation.

MC: So how do you deal with it? Just turn it off everyday.

LS: Yeah, I think you have to find a way to turn it off. If not, the path of least resistance is always to go to something that doesn't feel like something you've actually lived through, or is more real to your experience. It's a very strange conflict and dilemma in Singaporean filmmaking. The inside, and outside. You have to just turn it off, and don't care.

When we write scripts in Singapore, the dialogue can be colloquial, but the scene description is always fixed to perfect English. Which is interesting because, do you think in perfect English? Or are your thoughts actually in Singlish too?

LS: I guess people don't really know what to call (Singlish), but maybe we can call it a kind of creole. To us, it's its own system. And within this own system, there are certain nuances and subtleties that only that system can produce. The nuances of Singlish is something internally understood by Singaporeans.

MC: So when we make a film, I guess there is the thing you're saying, where the scene description is like, “Here is a coffee shop, and blah blah blah” but the dialogue is in Singlish, right? But the negotiation there is that everytime we're discussing the film outside of the script, it's usually just ourselves, so it's usually just in Singlish. Which is the same when we are discussing with crew and all that. I think that process creates the negotiation between that authentic representation and the more formal scripting language.

Courtesy of Emoumie Pictures.

Besides the Singaporean experience, were there other themes that you two hoped to explore in your previous films?

MC: As much as it comes from the Singaporean context or perspective, it's also always considering that human animal and its conditions. Wanting to present what we human animals are. It's something quite important to capture. Our experience overall, being in the world today. In these times where it's quite… As it's always been. It's always been tricky and testing but…

LS: In all our films, something we think about is how to push back at the sense of fatalism. It's something that's prevalent in today's times, all over the world. But of course when we present it, it's from our Singaporean perspective.

How does this then segment with your feature film “Revolution Launderette”? Because there's something cross-cultural there. It's set in Japan, and Singapore is also there, but not really.

MC: We knew a lot of the artists and musicians in that film, who make up most of the cast. Through our music (practice), and having interacted with them through music events and gigs. It was also our feeling that sometimes making a film can just be a collective expression with what we're all struggling against. There was sort of that commonality with our friends in Japan, trying to survive and make their art, their music. It just felt right at the time to make this thing together. But from a film perspective, for us it was, how do we create that as Singaporean filmmakers, instead of just making a Japanese film because we went to Japan. We wanted to make it with some Singaporean expression.

That's how we ‘perspectivised' it, and the connections between the people involved, some who we met on other travels. And their work intersected with how we were trying to express this film. I guess in that way, it's quite DIY and organic again, working on something together. But the timing was just right as COVID happened after that. We had that freedom to travel, why not we seize it and make something with the people around us?

Courtesy of Emoumie Pictures.

Something incredibly memorable for me in “Revolution Launderette” was the exercise book that the protagonists flip through and bring around.

MC: Yes, that was from my father. He created that book when he was twelve, in a kampong.

LS: Yes, in the 70s. So it wasn't a prop, it was actually an object that we found.

MC: (My father)'s crazy about football, so that was literally his sort of proto football news report on the World Cup.

LS: It's just that at the back of each newspaper clipping, there's all sorts of stuff about what was going on in the world at the time, and in Singapore as well. So that was interesting.

So what's next for Emoumie?

LS: We are now working on our next feature. It will be set in the 11th century in Temasek, weaving elements of folk horror, fantasy.

MC: It's a kind of anti-myth film, inspired by the way our region's history was told through myth.

LS: Through this absurdist lens. So that's currently what we're working on. We are also going to bring “Chomp it!” to the next festival, which is New Directors/New Films in New York, in April. And we are going to screen our previous film “Cannonball” at Asian Film Archive (AFA) as part of their Off the Catalogue programme in April.

Was it always on your mind, this myth of Singapore? It's always been Sang Nila Utama or Raffles, so I think there's this fascination with what was before.

LS: Yes, I mean something must have existed at that time. There's this almost blank space in history, where it's so interesting to see the possibilities.

MC: To look at the contemporary, through the lens of the past.