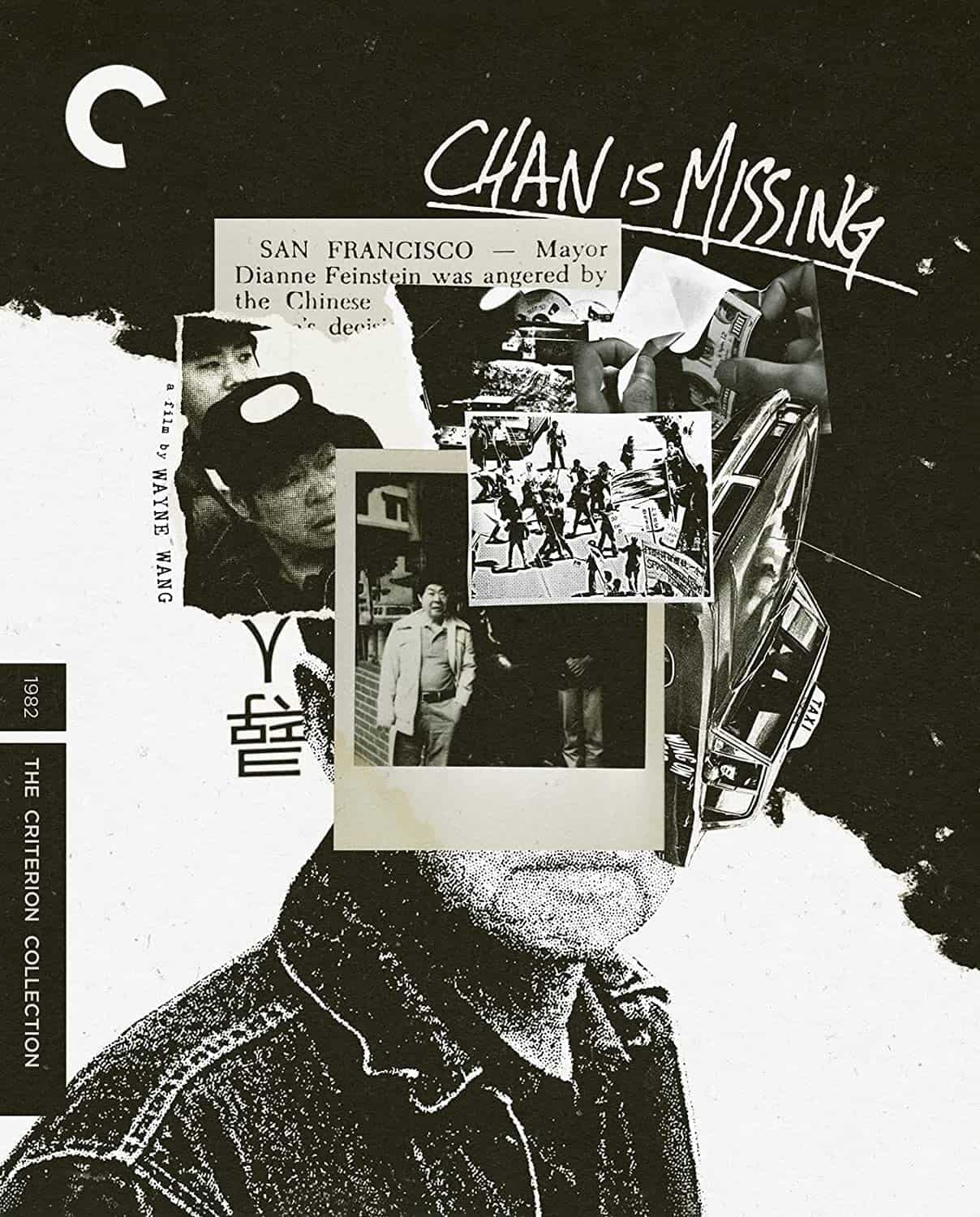

Wayne Wang's iconic 1982 film “Chan is Missing” is a staple of film studies and ethnic studies' screening lists across American universities, but each casual yet multi-layered second of its 76-minute runtime is replete with enough material to ponder for a lifetime. The director blends fiction with non-fiction in the depiction of a very real San Francisco Chinatown and parody with noir in its shifts between references to the Charlie Chan series and embrace of the detective style.

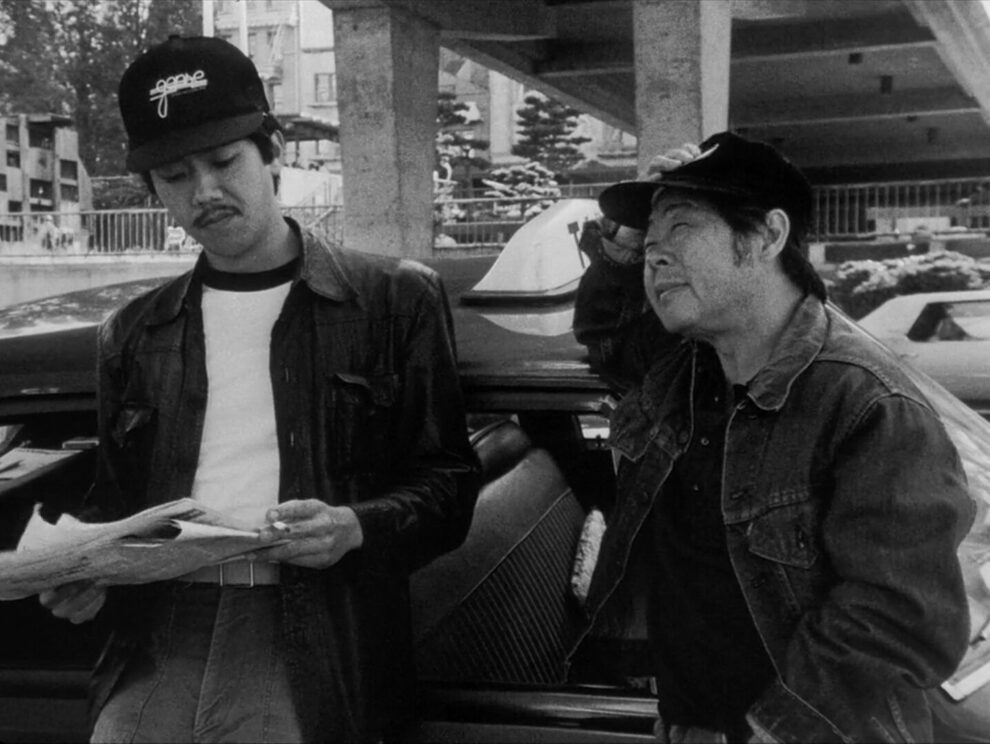

Chinese American taxi driver Jo (Wood Moy) and his nephew, Steve (Marc Hayashi), begin a search for the missing Chan Hung in San Francisco's Chinatown, to whom they had given 4000 dollars for a cab license. Their pursuit leads them to all corners of the neighborhood and into encounters with a variety of different characters, all of whom describe different portraits of Chan. Jo quietly narrates the film and the search, ruminating upon what they find and don't find while they search for this MacGuffin. What unfolds across the film becomes a beautiful depiction of the heterogeneity of Chinatown, questions about the innate tensions that exist within the community, and an interrogation of identity beyond what it “means” to be Chinese in the United States.

Although it is impossible to explore every unitary nuance embedded in “Chan is Missing,” a few elements stand out. In particular, the movie's intimacies are revealed in accents, linguistic choices, and how they pronounce names. The light tonal shifts in Jo's words juxtaposed is different from Steve's archetypically American lilt, just as they are both different from cook Henry's (Peter Wang) raging mainland Chinese accent when speaking in Chinese and his natural tendency to bilingually blend Chinese and English. Although they can understand each other, they can't always understand each other. This very difference alludes to the untranslatability between generations, lost in the subtleties that floated away with the decaying transmittance of accent and language between kin. The comfort in which characters navigate the hazy Chinatown restaurants normalizes a world in which they breathe a life that them and their ancestors have together created, a nod to Henry's comment that the Chinese have been in the United States for over a century, yet are still grappling with this seemingly superficial issue of identity thrust upon them.

From here, Wang shows that identity imposed upon a “Chinese American” by the external community is more than a matter of Chinese versus Taiwanese or American-born versus overseas-born. Jo and Steve search is vain for the elusive Chan, just as they are told to “look in the puddle” — a reflection — for him. Whether he is read as just a symbol of their own chase to understand themselves in a world that forces themselves to misunderstand or an actual person, is neither the point nor the ultimate question. Perhaps Wang refuses to even pose a question at all, a marked rebellion against viewership that insists upon reading from the film an issue to be solved or a crisis to be interpreted in non-white American communities.

In a delightful directorial choice, the film is nearly dearly devoid of white actors and characters — and those who are present are relegated to the status of clueless, passing extra. They are almost out of place, caught in a Chinatown world to which they don't belong, yet seamlessly so, as if they were never meant to inhabit that space at all. While Wood Moy as Jo is the film's measured hero and narrator, Marc Hayashi stands out as the ebullient young Chinese American Steve, who dutifully follows his uncle while posturing his way through every interaction, acting every inch the young American man of 80s filmography. The brash authenticity of his portrayal perhaps makes one wonder about his time in the extraordinarily influential Asian American Theater Company, through which the blossoming landscape of today's Asian American film and theater talent can easily be traced.

The music by Robert Kikuchi-Yngojo reflects and matches the film's generic evasiveness, switching between English-language classics and Chinese-language pop tunes of the era, and, of course, a classic noir score. With still images and montage, Wang — as editor — plays with pacing between different sequences, sometimes embracing a classical family home scenario while, in other moments, going full mystery. Sets oscillate between intimate environment and traceable spots within San Francisco, sprinkling an element of historical fiction within the movie simply through the locations.

The genuine charm of “Chan is Missing” makes its multilayered detective premise endlessly rewatchable. Wang's work is genre-defying in that he simply chooses to ignore conventional bounds altogether, instead creating a film that acts as geopolitical primer, a delicate portrait of a community, and meditation on identity politics and border anxieties in contemporary America, all in one.