by Iain Mitchell

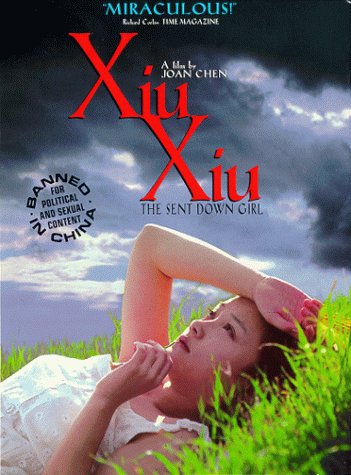

This year marks the 25th anniversary of Joan Chen's directorial debut, “Xiu Xiu: The Sent Down Girl”. It's a film that despite the star power of its director and visible cultural impact (its title is now likely more associated with the American experimental rock band who took their name from it) feels curiously under-seen these days.

Given the still ubiquitous debate about Asian representation in Hollywood, there's a sad irony that Chen, probably best known for her turn as Josie Packard in the original series of “Twin Peaks”, came to direct “Xiu Xiu” in part due to lack of opportunities afforded to her that weren't tired ‘Dragon lady' stereotypes. Even in Chen's highly positive experience of making Bernardo Bertolucci's “The Last Emperor” she noted in an interview with NPR that the film's producers were initially dissatisfied with her persona as a modern woman borne from Communist China; forcing Chen to augment herself to assume the “Western version of Chinese-ness” that was required for the role. In directing “Xiu Xiu” she had the opportunity to tell an authentically Chinese story, not borne from Western exoticism but real history. But it came at a great personal cost.

Based on a short story by Chen's friend Geling Yan, the film is set in 1975 during the post-Cultural Revolution movement known as ‘Educated Youth go up to the mountains and down to the countryside'. This was a program which ostensibly aimed to eliminate economic and social disparity between rural and urban areas and which, as the film's opening text tells us, “was intended to symbolize the powerful ideals of Communism.” As the film begins, our heroine, fifteen year old Xiu Xiu (the wonderful Li Xiaolu), is preparing to depart her hometown of Chengdu for the plains of Tibet.

We return to Xiu Xiu after she has spent half a year laboring in a rural factory. An exemplary performance report sees her recommended for deployment to an even remoter region to learn horse herding, with the promise of a prestigious post upon her return after six months. Her new station in a lonely Tibetan valley makes Xiu Xiu desperately unhappy; she feels bored and useless, has no water to wash with and is forced to share a small tent with her herding mentor, a kindly eunuch named Lao Jin (Lopsang). Before long, however, the pair form an unlikely bond. A turning point in the film comes when Lao Jin surprises his young charge with an outdoor bath he has built for her. When some rowdy officials descend upon the plains and nearly see Xiu Xiu bathing, Lao Jin threatens them away with gunfire. Xiu Xiu laughs joyfully as they flee on horseback, but the scene has ill portents.

The six months advertised for Xiu Xiu's deployment come and go, and no one from HQ arrives to fetch her. Eventually an official arrives and insinuates he can fast track her return home in exchange for sexual favors, and before long, other men from the Party are regularly descending upon the tent to have their way with her. Lao Jin can only look on in despair, reticent to intervene knowing that doing so would only destroy Xiu Xiu's illusion of recourse. In truth, the girl's fate is already sealed. Those in power have no interest in her beyond rape, and without an official endorsement, it is impossible for her to return to her hometown with any legitimacy. The latter half of the film, which sees Xiu Xiu's despair and degradation coalesce as her hope dissolves, is a difficult watch. We know that the story can only end in tragedy.

The incontrovertibly of Xiu Xiu's fate lends the film the tenor of a dark fairytale or fable, but in its clear indictment of the edicts and stooges of 1970s China, it can also be considered part of the ‘Scar cinema' movement which arose following Mao's death, seeking to process the cruelty that arose in the wake of the Revolution by focusing on “individual tragedies as microscopic representations of massive societal trauma”. Xiu Xiu is exactly the kind of girl to be prized and valued by the aims of the Cultural Revolution, but the disgusting abuses she suffers reveals the wretched self-servingness masquerading as service to “the powerful ideals of Communism”.

Chen's experience of making “Xiu Xiu” under Chinese jurisdiction without a government permit could almost warrant a whole film of its own. On location filming in a remote region of Tibet saw the cast and crew enduring a month of privation, before the interior shots in Shanghai had to be rushed to completion when Beijing officials became suspicious. There was also a significant chance that the work would be for nothing, were it not for the success of Chen's parents, tasked with smuggling the footage out of mainland China in a suitcase.

Needless to say the film was blacklisted by the Chinese authorities, and subsequently marketed in the West with the tagline ‘Banned in China for political and sexual content'. This tackiness was to Chen's chagrin; fundamentally because she did not intend “Xiu Xiu” to be a political film. For Chen, who was almost the same age as her heroine in 1975 and only escaped being ‘Sent Down' herself by virtue of being discovered by the Shanghai film studios (some sources say by Madame Mao herself), the film both represents what her life could have been, and in Xiu Xiu's microcosm, the trauma of those forgotten youths whose dreams were trampled underfoot.

“I didn't mean to make a political film,” she explained to Filmmaker magazine, “I wanted to make a film about my generation, our collective longing, our collective nightmares… I wanted to make a piece of cinema.” “Xiu Xiu” is most certainly a piece of cinema, and one that deserves to be seen.