Jizo statues are a fascinating part of Japanese folklore. Often sighted near Buddhist temples, graveyards and sometimes on roadsides, they provide protection to travelers and the souls of children and unborn babies. They can be small and unassuming, with friendly faces like a classic Buddha, but sculpted more in the shape of a garden gnome. One such statue can be found in Sayama City on a small modern-day intersection; the statue and adjoining temple have been there for over 300 years, standing as a preserved relic of the Edo era, but the world around it has changed drastically. It sits awkwardly in the road, like a chunky doorstop that wedges open a portal between the past and present; Sayama resident and director Mitsuo Kurihara has built a strange, whimsical story around that very idea with his extravagantly-titled micro-budget feature film, “The Haunted Jizo of Shimo-Mizuno, Sayama City”.

“The Haunted Jizo of Shimo-Mizuno, Sayama City” review is part of the Submit Your Film Initiative

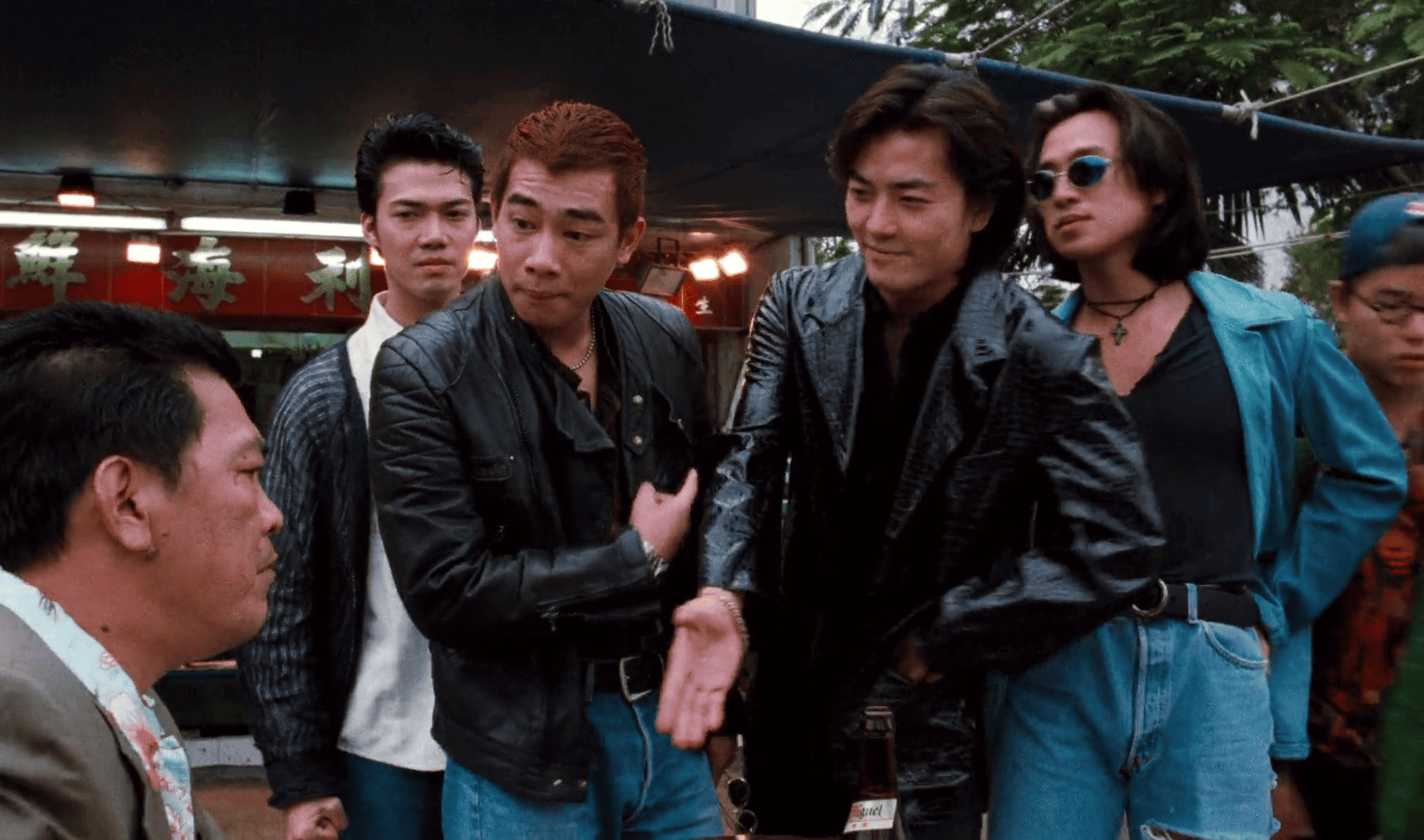

The title screams ominous, and its mysterious synopsis deepens the intrigue: “An evil ghost is eliminated by the power of the Haunted Jizo.” It's clear that Kurihara is a filmmaker who wants to keep his cards close to his chest at every turn, because the opening act of this fascinating but baffling work is a seriously weird blend of docu-drama, psychological thriller and, yes, a musical. The voice of local woman Yukie (Chisa Hasegawa) sets the scene well, clueing us in to the history of Sayama's jizo and the prosperity it helped cultivate through good crops in the Edo period. The film then immediately shifts gears and introduces the viewer to its choric characters: two guitar-playing school girls (Chiyuri Ito and Ami Ryu) who jauntily score the action and intrigue of the story going forward. Ito and Ryu provide frequent interludes to Yukie's unfortunate plight: her sham marriage to the boorish, abusive Joichiro (Takahiro Ono) takes a turn when he disappears, only for him to return after seven years, one day before he is legally allowed to be declared dead and she can get a divorce. But Joichiro returns a changed man; he has amnesia, and suddenly, he's very kind and affable. A future begins to blossom for the couple, yet the dark shadow of his mysterious disappearance begins to grow in the background.

The exploration of these grounded central relationships is where the film works best. There's a warmth and empathy in the early scenes between Yukie and her in-laws (Hibiki Murayama and Emi Mori), and in the absence of their irritating son, they adopt Yukie as the model child they never had. When Joichiro returns, Ono and Hasegawa have a gentle chemistry that works against the grain of the story and takes it to fresher, more involving places, and when Kurihara allows the drama to settle into this register, it's a good example of the humanity found in independent Japanese cinema. It's clearly where Kurihara's vision feels most at home, patiently observing the quiet tensions of a dysfunctional family who were torn apart by bizarre circumstance and reconnected years later for the better.

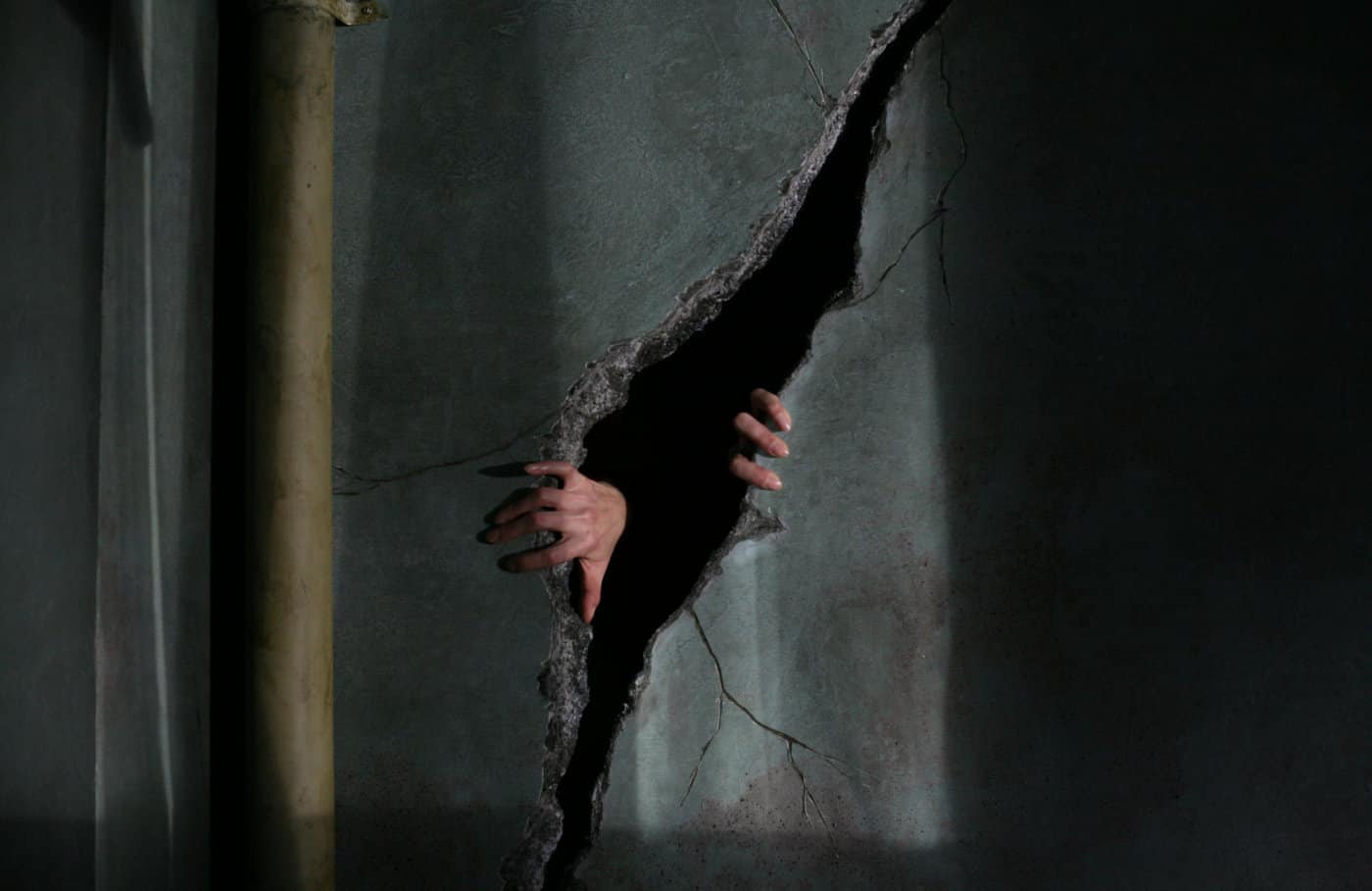

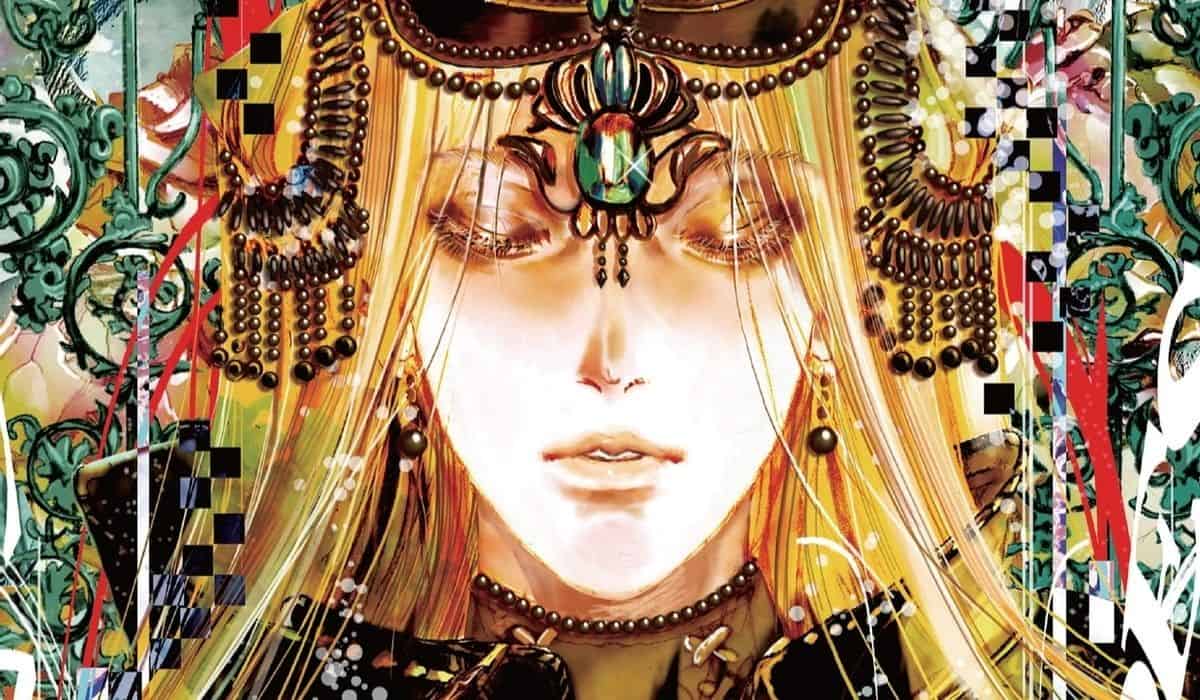

Unfortunately, the constraints of its budget really do show when it tries to branch out into different genres. The film's visual imagination is limited, particularly struggling to establish the sense of atmosphere around the central statue that it desperately needs. The jizo is barely featured on-screen, feeling like an afterthought when its title otherwise places so much emphasis on its narrative importance. There is admittedly one bone-chilling scene later on that shifts gears successfully into horror, conjuring an eerie image that mixes the stylish make-up and costuming of “Kwaidan” with the slow, creeping dread of Kiyoshi Kurosawa. That being in here shows that Kurihara has an interest in drawing out the spookiness of his material, but when aligned with the rest of the film's underlit interiors and overexposed exteriors, it shows the flaws of the work all the more glaringly.

The rest of “Haunted Jizo”‘s entertainment value comes from the music grafted onto the story through its choric characters. There's perhaps a better, more adventurous work to be found in a full-on musical about the weird happenings around the eponymous statue, and the collaboration between musician Ryota Komiya and lyricist Kenichi Nishio creates some catchy songs that are enthusiastically performed by Ito and Ryu. Anyone familiar with the role of shrine maidens in Japanese culture will find their presence intriguing; whether they are featured simply to narrate the story or provide protection to the ancient site is up for debate, but the harmonious guitarists are a quirky and enjoyable addition to a film that veers inconsistently between low-budget horror and low-key drama.

The overall picture becomes slightly muddled when the story takes a turn towards resolving its central mystery. Watchful spirits and malevolent ghosts haunt Joichiro's reappearance, and the visual register does not alter enough to pull off this drastic shift. As it stumbles away from the humanity of Yukie and Joichiro's relationship, its emotional pull lessens and the finale is a flop, relying on a series of amusing end titles that tie the story up in a jokey anti-climax. The impression left by the ending is a cloudy one, caught in between being humorously irreverent and disappointingly stilted.

Kurihara's ultimate mission as a director is to represent Sayama in an interesting light. It's his hometown, and he is clearly drawn to its quirky aspects and the sleepy rhythms of everyday life that can be found on every street. Taking all that into consideration, “The Haunted Jizo” is an affectionate and singular drama that tries to combine darkness and light, and the real and the unreal. What it lacks in refinement, it makes up for in originality, as it is unbound to standard generic modes and structures. One never knows where “The Haunted Jizo” could go next, and its unpredictability gives it an intriguing energy, even when the complete picture is frustratingly inconsistent.