Despite some controversy from the 1999 Cannes Film Festival, which eventually led Zhang to withdraw both of his films from the program, “Not One Less” became another international success, netting four awards from the Venice Film Festival, including the Golden Lion. The script is adapted from Shi Xiangsheng's 1997 story “A Sun in the Sky',' and takes place during the particular decade, when primary education reform had become one of the top priorities in the People's Republic of China. About 160 million Chinese people had missed all or part of their education because of the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and in 1986 the National People's Congress enacted a law calling for nine years of compulsory education. By 1993, it was clear that much of the country was making little progress on implementing nine-year compulsory education, so the 1993–2000 seven-year plan focused on this goal. One of the major challenges educators faced was the large number of rural school children dropping out to pursue work.Another issue was a large urban–rural divide: funding and teacher quality were far better in urban schools than rural, and urban students stayed in school longer.

Buy This Title

by clicking on the image below

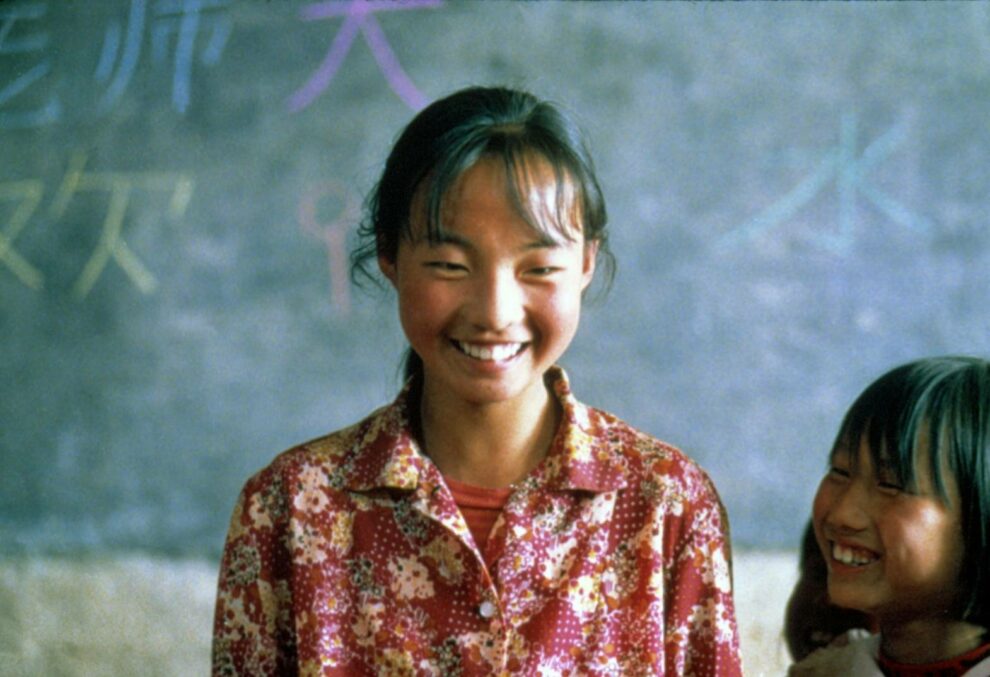

In this particular setting, 13-year-old Wei Minzhi arrives in Shiquan village to substitute for the only teacher there, Gao, who is about to take a month's leave to take care of his ill mother. As the phenomenon of children leaving school to go to work in factories has become a major issue for the village, Gao promises Wei to give her 10 yuan, on top of the 60 she is to receive from Mayor Tian Zhenda, if no student has abandoned school by his return. However, when one of the students, troublemaker Zhang Huike leaves for the city, Wei tries to bring him back, and is willing to go to extremes to accomplish that.

Zhang directs a tender and very moving film that focuses on presenting a number of faults of the Chinese system and the overall bureaucracy that dominated the country, in contrast to the benefits of patience and persistence of the individual. The critique essentially starts from the beginning of the film, with the poorness dominating the rural setting the first part of the movie takes place in being quite eloquently portrayed, and the fact that the substitute is a 13-year-old bordering on the absurd. Expectedly, with the financial and educational level being so low, and her being as inexperienced as possible, Minzhi faces intense problems not only teaching, but even implementing discipline in the classroom, with Zhang Huike being the main problem in that regard. The fact that she goes to all this trouble to bring up a kid who caused so many problems, makes her actions heroic, with Zhang combining the two aforementioned axes of the movie in masterful fashion.

Check also this video

The second part, which takes place in the city, highlights a number of different problems. The difference of the people living in urban and rural settings is quite obvious, with Minzhi barely being understood by the locals when she talks, but that is just the beginning of what Zhang shows here. Alienation, lack of compassion, and an intense obsession with bureaucracy create a Kafkaesque setting that becomes even crueler considering the age of the individual that has to face these series of dead-ends. That the only help she receives from a girl her age, she has to pay for, highlights this aspect in the most eloquent fashion, with the same applying to the fact that even when she does finally get a break, the people who give it (the TV channel) seem to also want to use for their own purposes, of falsely praising the educational reforms, and thus the government that employs them.

Truth be told, when one watches “Not One Less”, one would probably wonder how it passed Chinese censorship, with the government even going a step forward, by launching a promotional campaign of the film in the country. There are, however, some reasons for this, although Zhang has implemented them subtly in his narrative. That various people eventually do help her, occasionally with her not even asking, and the fact that when the TV station director learns of Minzhi troubles, both immediately helps her and chastises the low employee for shoving bureaucracy to her, moves to that direction, with a direct wink to the higher echelons of the Chinese system and the kindness of the people. The ending, with its intensely romanticized approach that has the Huike returning to the village with a triumphant Minzhi through private donations, also moves in that regard, as it seems to state that in the end, the system works, while praising the perseverance of the Chinese people, in a rather sanctimonious approach.

The fact that the aforementioned are essentially the only non-realistic aspects of an approach that lingers between neorealism and the documentary, highlights even more intensely that perhaps Zhang Yimou made some compromises in order to pass censorship. These, however, although they do bring the level of narrative quality a bit down, do not detract significantly from a movie that is very difficult not to characterize as masterful.

Particularly the way Zhang implemented realism in the film, by shooting in the particular places and casting actual people from the area adds an intense sense of authenticity that is also intensified by Hou Yong's excellent cinematography, which presents all that is happening with no punches-pulled. Particularly Wei Minzhi is a wonder to look at throughout the movie, in a performance that highlights both her talents and Zhang's work with her, although the fact that Zhai Ru's editing was implemented to make the whole thing appear a bit better is also obvious. Regarding the editing, the job done in the particular department is also top notch, with Zhai Ru implementing a relatively slow pace in the mountains and faster in the city, which fits the story nicely, while some moments of montage, like the “Are you the station manager?” one definitely staying in mind.

Despite the controversy the film brought particularly among critics, “Not One Less” is a triumph of neorealism and an extremely well-shot movie that manages to present its comments in the most eloquent fashion while boasting a captivating story throughout.