For the last few months, trades, outlets, brands across the world have all wanted their slice of discourse in the marketing and publicity heaven that is Greta Gerwig's “Barbie” (2023). For a website dedicated to Asian cinema, it might be argued that this smidge of pie was not ours to claim. Yet as I sat through its credits, celebrating our collective womanhood, a film by Lee Sang-Woo came to mind. 11 years ago, in another “Barbie” (2012), then-child actress Kim Sae-Ron quipped, “A pretty and skinny person like (Barbie) doesn't exist. If she does, then she must be an alien.”

Alien, meaning someone not of this planet, or perhaps, someone not of this country. Lee Sang-Woo's “Barbie” once illuminated an uncomfortable truth: the Eurocentrism of Barbie, and at larger value, the Eurocentrism of many American owned megacorporations that purport themselves to be global, all-inclusive, normal: Mcdonalds, Disney, Vogue. Thinking of “Barbie” (2012), alongside a slew of films that have confronted our tumultuous relationship with the utopic America, such as “On Happiness Road” (2017) and “Factory Boss” (2014), it became overwhelmingly clear to me that despite most of us (me included) never having stepped foot in the states, semblances of American identity have lodged themselves everywhere. With the intentional pervasiveness of American products, media, and messaging in all aspects of our lives, at what point can we too consider ourselves matriculated into American culture and identity? At what point can we, perhaps controversially, consider ourselves American?

We simply cannot, and so enters the term “Americanization”.

Since the 20th century, to be ‘westernized' or ‘Americanised' has harbored positive connotations of being modernized, fashionable and progressive. At the same time, copying America has earned accusations of populism, of siding with the colonizer, and many struggle with the wonder of what might be lost. Double entendres such as this confuse, conflate, frustrate. And inspire filmmaking. So rather than comment more upon this year's “Barbie”, this article will attempt to bring together 3 filmic instances of East Asian responses to being ‘Americanised' through toys and children's media, examining their silent but mass naivete, revolt, acceptance, understanding against unstoppable (American) hegemonies in our daily life.

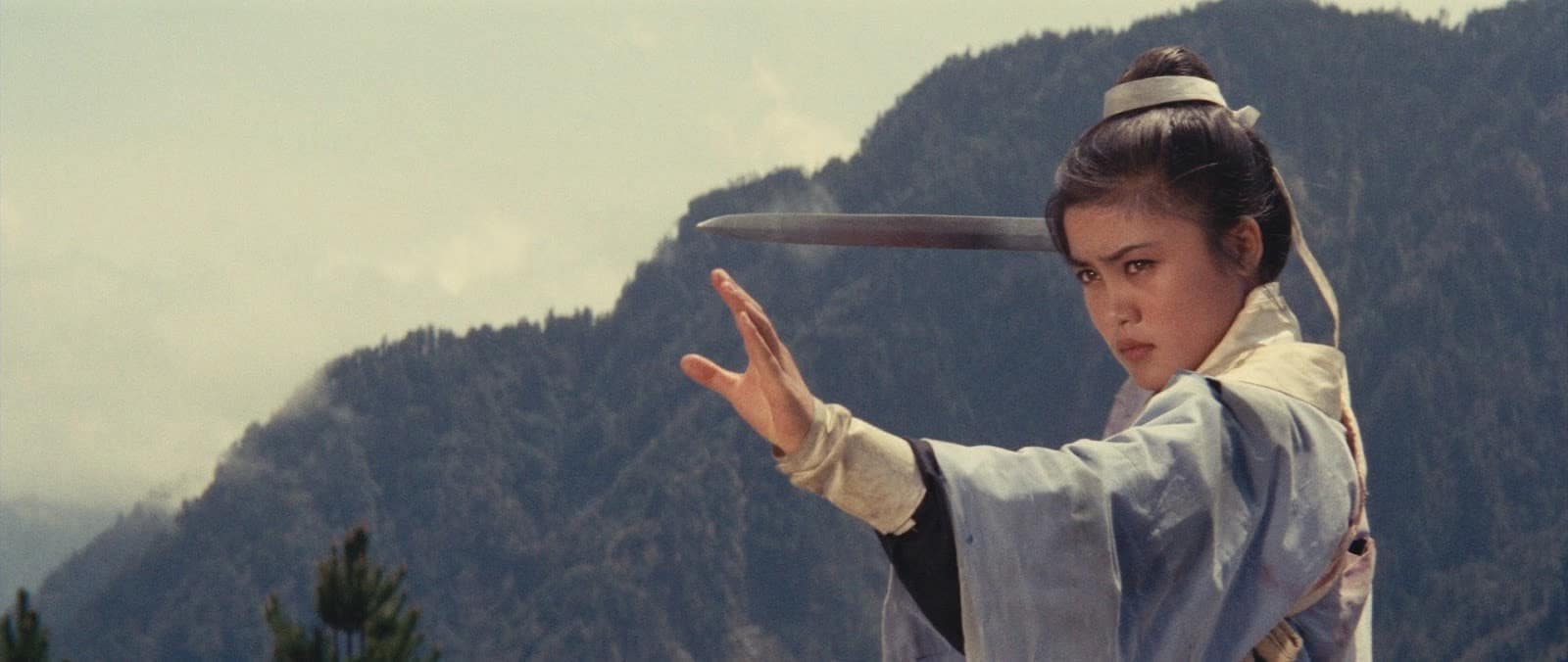

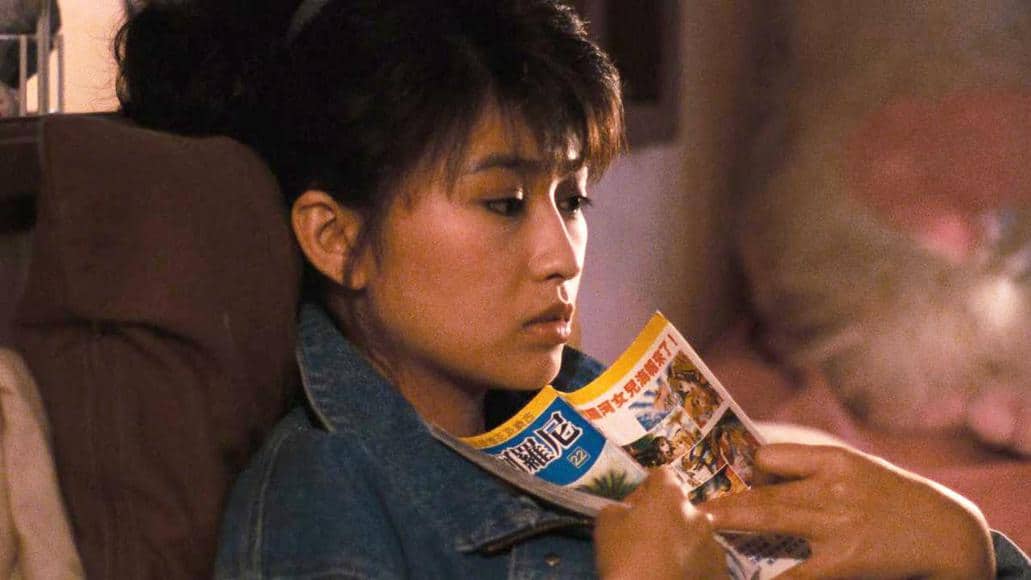

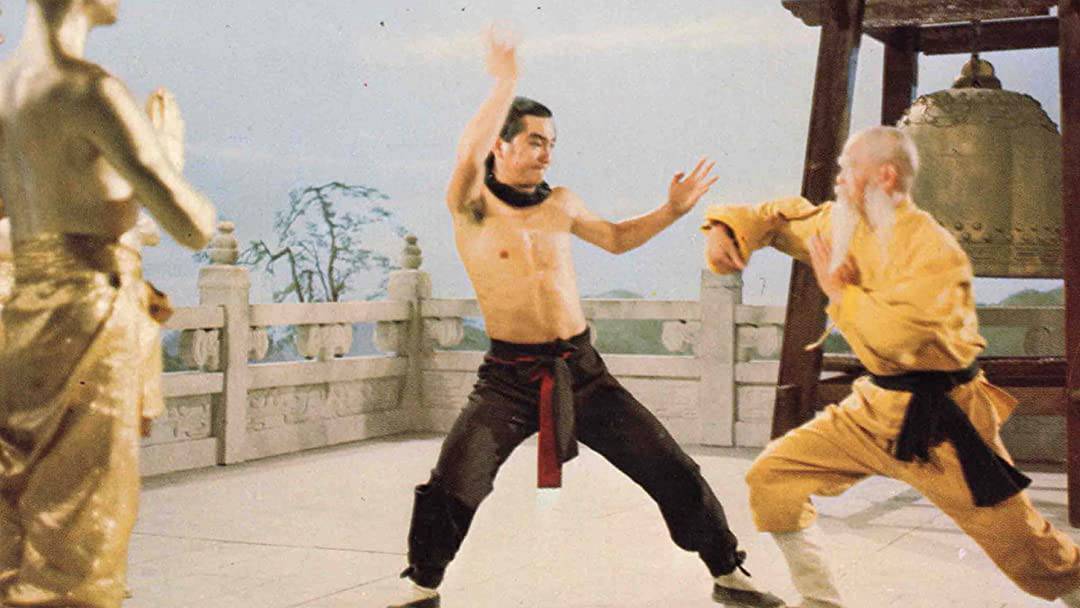

On first look, Korea's “Barbie” (2012), China's “Factory Boss” and Taiwan's animated “On Happiness Road” seem most united by their problematization of a blond, fair skinned female emblem. All 3 make enough screen time to confront this image as perhaps the most telling, evocative and human symbol for an empty ‘American Dream'. “Barbie” (2012) revolves around poverty-stricken sisters Soon-young (Kim Sae-Ron) and Soon-Ja (Kim Ah-Ron). The former wants to keep her loved ones together in Korea, while the latter idolizes Barbie and dreams of escaping her home situation. Conflict arises when they realize Soon-young has been sold by her uncle for an American family to adopt, in essence becoming a disturbing form of American commodity. “On Happiness Road” by Hsin Yin Sung, a coming-of-age dramedy in post Chiang Kai-shek Taiwan, similarly frames America as a child's utopia, a juvenile impulse with dire consequences. Protagonist Chi (Gwei Lun-mei, Bella Wu) is addicted to the Japanese anime series Candy Candy, and fantasizes about herself as the titular tender, blonde damsel, moving to New York one day and finding a Prince Charming. Years later, married to an American and estranged from her Taiwanese family, she finds life still empty. “Factory Boss” (2014) follows middle aged Lin Dalin (Yao Anlian), a Chinese toy manufacturer who dreams of innovating his own product line, instead of working for the Americans. At its core, the story exposes the reality of common products, Barbies included, being “made in China” at unbelievably low costs, at the expense of thousands of workers' health and livelihoods. Unlike the first 2 titles, “Factory Boss”' critique is not so much aimed at a journey upwards to America, but rather the downward consequences of America's own unethical consumerism. Yet though the trio take vastly different issues with the concept, their emotional arcs boil down to 2 key takeaways.

First, that the USA's level of influence in our personal lives and well-being should be examined. The films also take a consistent stance that it should be problematized. Second, despite this problematization, the USA's influence is consequently immovable. We must coexist, but now aware of the distinctions between us and it.

Check also this interview

“Life in Plastic. It's fantastic.”

Just as Gerwig's “Barbie” dolls start unaware of harsh reality, so do all our East Asian protagonists, who stubbornly dream of a better life in America. Or in “Factory Boss”' unique case, a dream to escape it. Unlike Chi or the sisters, Dalin begins already aware of America's unfair power over him, but maintains an unwilling allegiance out of a lack of choice. His naivete comes from the belief that he can, with enough effort, remove America from the equation and produce dolls of his own design. When comparing across the 3, “Factory Boss” takes a step further that begins near the end of Chi and Soon-Ja's journey, yet mirrors a continuing vicious cycle of idealism. These consistent dealings with idealism determine that its death will signify the beginning of their distinctions between their own identity, and the learned ‘American' identity.

At this point however, the characters are matched by their internalization of this far fetched dream into the personal. Soon-Ja, Chi, and Dalin all want, in their own way, to become American themselves. To partake in what they believe to be a bliss and fulfillment that can only be associated with Americanization. Yet as our characters pine for freedom and purpose, emboldened by the American ‘voice' in their life: makeup, piles of silicone dolls, Marilyn Monroe posters, the character of Candy, they are oblivious to its alienations.

Like the children they are, Chi and Soon-Ja re-enact their desires from the USA without much filter. Chi's first ever bite of a Hershey's bar catapults her into an orchestra-filled dreamscape of Times Square overflowing with confetti and chocolate. Expectedly, in this fantasy sequence, Chi is white, long-haired and blonde. When Soon-Ja recites the slogan “Quench your thirst with a Cola” as she hands over a Pepsi to a white man, as if it were normal dialogue of the day, it lays bare the true disconnection of many who have similarly idolized America, only to later be disappointed. It demonstrates the unintended, disastrous results of misinterpreting and collectivizing constant manicured messaging from America into a whole of itself. The Barbie world where only beautiful dreams and Coca cola reside.