Refusing the blistering politics of identity is a radical move in a (cinematic) decade where representation is royalty, but it's something that Seo Ah-hyun does not take lightly. The filmmaker's quietly ambitious debut feature, “Queer My Friends,” admirably never bends to the crucifying Enlightenment dualities that practically beg to be used in a work about her best friend, a gay Korean Christian man: religion versus reason, self versus other, truth versus reality. Instead, Ah-hyun — as she is referred to in the film — trades dualisms for a dualistic monism in the parallel-woven depictions of her friend Song Kang-won and herself, a straight Korean woman, over the course of five years.

Check also this interview

Narrated à la Sandi Tan's “Shirkers” but intimate with the intricacies of queerness in East Asia like Yan Zhexuan's 2020 documentary “Taiwan Equals Love,” the filmmaker embraces intentional subjectivity as objectivity, put forth by Donna Haraway in her famed essay on situated knowledges. She is not afraid to be brutally honest, questioning which side of queer protests she would be on if Kang-won weren't her friend. “Repent! Repent!” shout Christian counter-protestors in English at the Seoul Queer Festival. Ah-hyun briefly joins in, tentatively, unclear herself if she's joking. However, in a country where nearly one-third of the population is Christian, Kang-won refuses himself a come-to-Jesus moment. There is no one truth, no singular right or wrong. Homosexuality may be a sin, but life as a gay Christian man still goes on. This isn't his fight against the system.

As Kang-won is excitedly promoted to U.S. army sergeant in the estranging cradle of toxic masculinity of a military base in Germany, Ah-hyun is desolate and lost while swaddled in the protective embrace of her Christian brothers and sisters in Korea. “We believe that God will bring with Jesus those who have fallen asleep in him,” murmur the worshippers, huddled in a circle. Ah-hyun skillfully shifts back and forth between their oppositional lives without narrative whiplash, asking the viewer to trust in her ability to bring together both, in a two-mirror kaleidoscope of twenty-something-year-old Korean life.

But, like any attempt at romanticization, placing Kang-won on a pedestal must come crashing down. Ah-hyun longs for the full vulnerability and confidence of her best friend, only to realize he cannot even emotionally open up to himself, sobbing, “Who can I show this side to? My boyfriend? God?” The film thus reveals coming out to be a mere bump in the much larger quest for self in modern times, where performative masculinity smothers and the doctrine of self-reliance is brainwashed into each and every citizen of the Western world.

Paulo Coelho's “The Alchemist” hangs low over Kang-won as he renounces his Korean citizenship for a future (and citizenship) in the United States, only to later return to Korea to seek himself after being discharged from the U.S. army due to depression. However, his brusque rejection of heteropatriarchal nationalism clips him in the shoulder on the way out, as he is refused a work visa in Korea because he never served in the country's military, a requirement for all men. It's the harshest of ironies to choose individualism over a collectivist society, only to face cruel rejection when desperate to return to the still-warm confines of the latter. “Queer My Friends” tells us to be true to ourselves but points to the bleak reality that we'll never be who we really are.

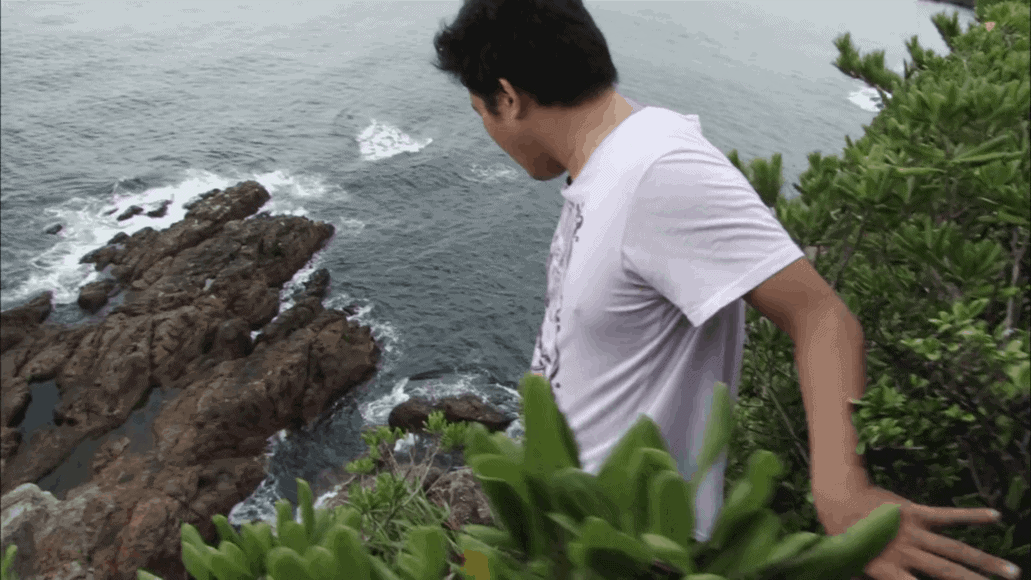

Over the course of the film, Ah-hyun hesitantly takes up the imperative of the reflexive documentary form, increasingly removed from her positionality as woman-behind-the-camera. Song Kong-seok's cinematography is effective enough for this purpose, but the material deserves far more, especially in moments of hyper-personal revelation. Often, the camerawork is far too distanced and almost defamiliarized from its subjects, giving the film a vlog-like quality. Even less discreet is Ah-hyun's use of mirror shots to literally turn the camera on herself, brandishing her video camera and RØDE mic to the viewer. What remains is the B-roll footage of urbanity that ultimately ground “Queer My Friends” in the mundanities of quotidian life.

“What can we do when we are not accepted for who we are?” Ah-hyun asks, clear that she can't answer this question by herself. This isn't just about being gay in Korea — or anywhere in the world, for that matter. Kang-won swaps Korean for American citizenship and musical theater for the American military, all after coming out, while Ah-hyun is static in Seoul, trying to make it in the film world. Nonetheless, Kang-won's influence so subtly and profoundly seeps in, unconsciously forcing her to confront queerness beyond self-identity: as a mode of articulation and a way of being in the world. As the filmmaker, Ah-hyun is wholly introspective but rarely self-indulgent. The complete unsettling of her own biases around queer existence, hardship, and joy are not within the confines of this story.