We are living with a generation that is increasingly obsessed with multiverses and the fluid concept of time, so it was only genius for Kazuaki Kiriya to hop on the bandwagon and deliver his rumored ‘final piece of work', set in Japan of the near future. Working with concepts along the veins of his previous apocalyptic “Casshern (2004)”, the director known for his outlandish ideas, takes us on a time-bending journey of samurais, nuclear attacks, and magical grimoires.

From the End of the World is screening at Japan Cuts

As the great expanse of earth gives way to a bleak forest fire, a child suddenly appears and finds herself in the fray of death and destruction in Edo Japan. Everything is a picture of charcoal-blackness but the blood that flows around her is a sea of striking red (expertly manipulated by cinematographer Chigi Kanbe). Color then returns as the picture transitions to the modern world. Hana (Aoi Ito), an orphan girl, is truly alone, as she witnesses death consume her grandmother. There is no time for sorrow as Shogo (Katsuya Maiguma) and Saeki (Asahina Aya), of the National Police Agency enter her apartment and interrogate her about the weird dreams she had been having.

Check also this interview

Afterwards, like a reverse of “Thermae Romae” (2012) and its time-shifting Roman Onsen Architect, a relaxing bath affair leads Hana back into the alternate universe of 16th century Japan, where she encounters a seer (Mari Natsuki) and the child (Mio Masuda), who set our 17-year-old heroine on a journey to save the world from impending doom, as the only one who could alter the fate of the Earth through her dreams and the aid of her National Police agency pals.

The story then gets increasingly discombobulated as Hana fleets between worlds and more textures are added to the mix. Kiriya tries to make sense of the story with the inclusion of many dialogue-driven bits throughout, but the more the characters explain, the more we are sunk into a pit of confusion as “From the End of the World” suddenly veers into the realm of philosophy and of finding one's purpose.

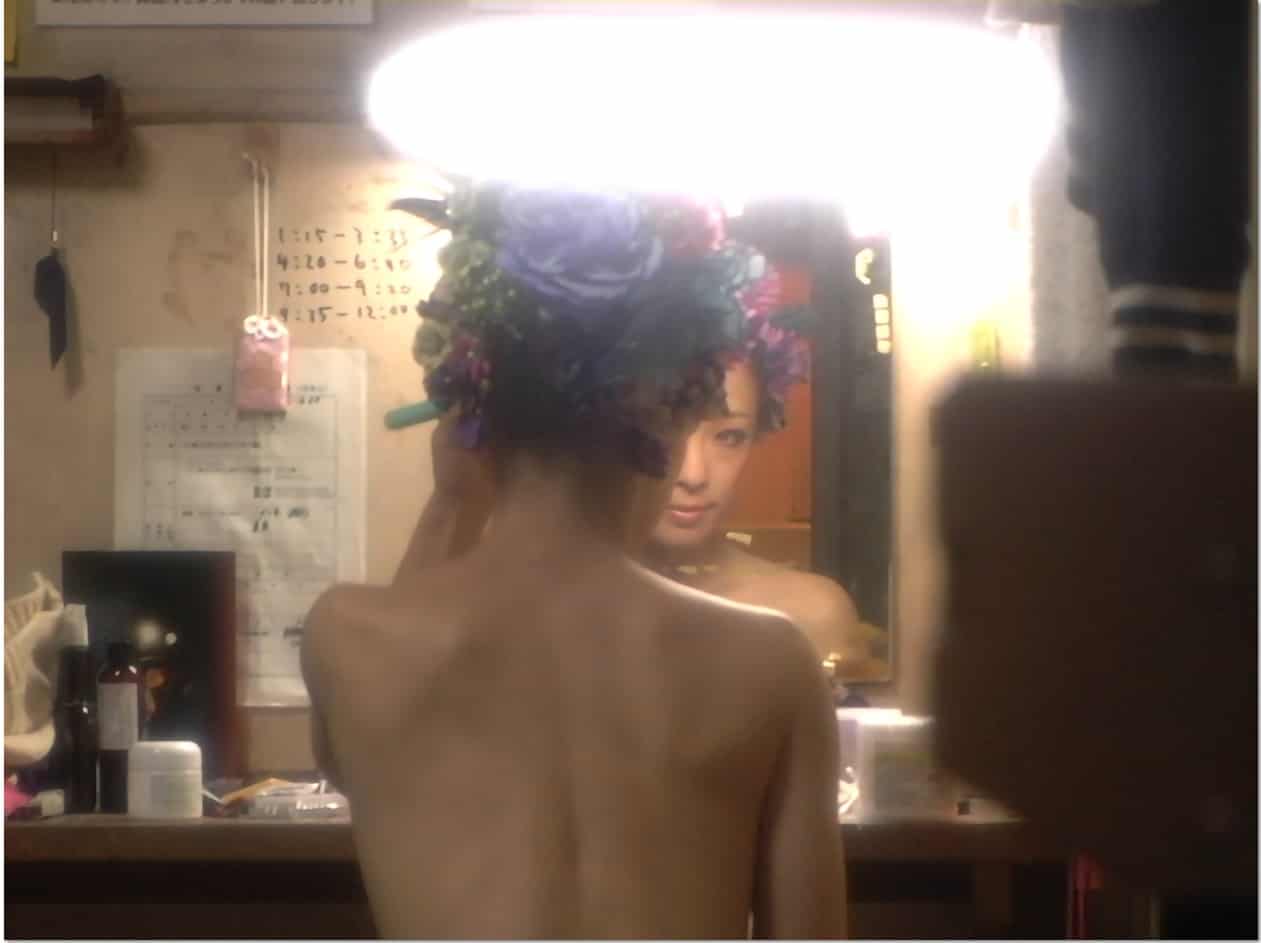

Like her character, who shoulders the catastrophic end of the world on her shoulders, 17-year-old Aoi Ito means business, with a zesty performance of adolescent angst and unbridled passion manifested in her numerous tearful displays. The rest of the cast is also none too shabby, with Mari Natsuki giving an added touch of campiness with her character that gives Helena Bonham Carter's red queen a run for her money. Aya Asahina' Aya's's Saeki also displayed incredibly sleek moves that gave the film a dose of adrenaline-pumping action.

But even with its committed cast, delightful colour palette and play of lighting, as Kazuaki Kiriya's works have come to be known for, nothing can save this from stretching its 135-minute-runtime thin. Stay for the gorgeous visuals but take it with a pinch of salt by way of corny CGI and confusing storytelling that fumbles along trying to be the next “Inception” (2010) but falling flat with an overly inflated plotline that might very well be the end of Kazuaki's Cinematic World.