by Earl Jackson

For years lesbian feminist film scholarship entailed archeological detective work, most notably excavating the subtexts of Rebecca (Alfred Hitchcock 1940) and The Haunting (Robert Wise 1963). In a peculiar reversal, I am going to try a similar dive into a film to salvage its male homosexuality. While Rebecca and The Haunting may have repressed latent desires under a gothic mood piece, Marry My Dead Body ( harbors a sexual ambivalence within a blatant coming out wake. In doing this, I am actually not faulting the film but rather the limitations on sexual legibility under even the most seemingly benign, apparently inclusive heteronormative social order. Moreover, while exposing what the film cannot do, I want to underscore what it does beautifully: it dramatizes as a default aspect of contemporary life, a kind of habituated melancholia interrupted by an intimacy that at first seems like an assault.

The basic plot is actually more of a hook as its initial titillation quickly gives way to a police procedural and the emotional struggles of a grieving family. Circumstances force straight, homophobic vice squad police officer Ming-Han Wu (Hsu Kuang-Han) into a Taoist ghost marriage with Mao Pang-yu (Lin Bo-hong), a young gay man killed in a hit- and-run. Although the Chinese title of the film would be impossibly awkward in English, it is far more accurate: 關於我和鬼變成家人的那件事 “On the Incident in which ghost and I become family” Marry My Dead Body is misleading, first of all because before the ceremony the ghost refused the proposal but his refusal was misread as acceptance because of a mishap with the divination blocks -so the title suggests a request he never made. Secondly of course, the marriage was to the ghost, not the body, and in larger terms the title errs because in the film bodies are on display but never actually on offer. And that bait-and-switch occurs in the opening sequence and continues through much of the film.

The film opens at night in a Taoist temple. An old woman (Man-Chiao Wang) brings a tray of tools to the side of a coffin and takes a lock of hair from the corpse and meticulously trims its fingernails (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The grandmother (Man-Chiao Wang) takes what she needs from Pang-Yu Mao's corpse.

This is the only glimpse of the body of Mao Pang-yu, supine and ready-to-hand but utterly unavailable. That spiritual care of the remains is then followed by a garish, apparently all-male gym filled with hunky metrosexuals working on their own bodies. Among these self-fashioning bodies comes a young man (Lin Da-her) who sits on a bench looking at Officer Wu doing arm presses (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Officer Wu has caught the attention of the suspect

Wu exchanges seductive looks with the man and heads to the lockers, closely followed by the young man who disrobes and beckons Wu to the shower (Figs 3-4). Wu seems to be ready to enter when he pulls out his badge and incongruously demands the naked man to produce his ID.

Fig. 3. Officer Wu deploys a seductive look to hook the suspect.

Fig. 4 Officer Wu drops the seductive act and flashes his badge.

The scene is structured as police entrapment of a gay man, however, Wu and his assistant officer are there on a tip that the man was about to do a drug deal. They search his locker and find a baggy of cocaine. When the man protests, Wu flips him to the ground and says, “You people make me sick” He claims he meant rich people, but the entire scene screams homophobia. It is also unclear why Wu decided to flirt with the suspect rather than simply demand to see his locker, since this was a drug bust and not a sex offender case. This is the first instance in the pattern of offering one's body only to immediately not only withdraw the offer but to deny it.

Wu is severely criticized for his conduct by his fellow police officers who call him on his homophobia. Their reaction recalls an actual case in which the police were found guilty of much more serious oppressive tactics. In January, 2004, police raided a gay male sex party and televised 93 men in their underwear sitting on the floor. They were arrested, tested for AIDS and the results were also publicized. Even though the presence of condoms indicated safer sex practices, the police attempted to charge some of the men for endangering the lives of others. Even at the time these police actions were roundly condemned, and it remains a black mark on the record of progressive attitudes toward civil rights for sexual minorities. Characterizing Wu's actions as homophobic and even obliquely associating them with the 2004 case, sets Wu up for the karmic payoff of the ghost marriage.

After a reckless chase, Wu was collecting evidence a suspect threw out the car window, when he picked up a red envelope. Immediately several aunties, including Pang-yu's grandmother leap from hiding places and announce to Wu that picking up the envelope requires him to submit to a ghost marriage (Fig 5).

Fig. 5. The Aunties spring a Ghost Marriage trap.

Already annoyed at the idea, he becomes incensed when he sees the photograph and realizes the intended partner was male. He flashes his badge at the aunties and discards the envelope. They warn him of the consequences of his refusal which he ignores, even when the envelope clings to his crotch (Fig 6), the first of several times the film will focus on his lower body.

Fig. 6. The ghost envelope clings to Wu's crotch.

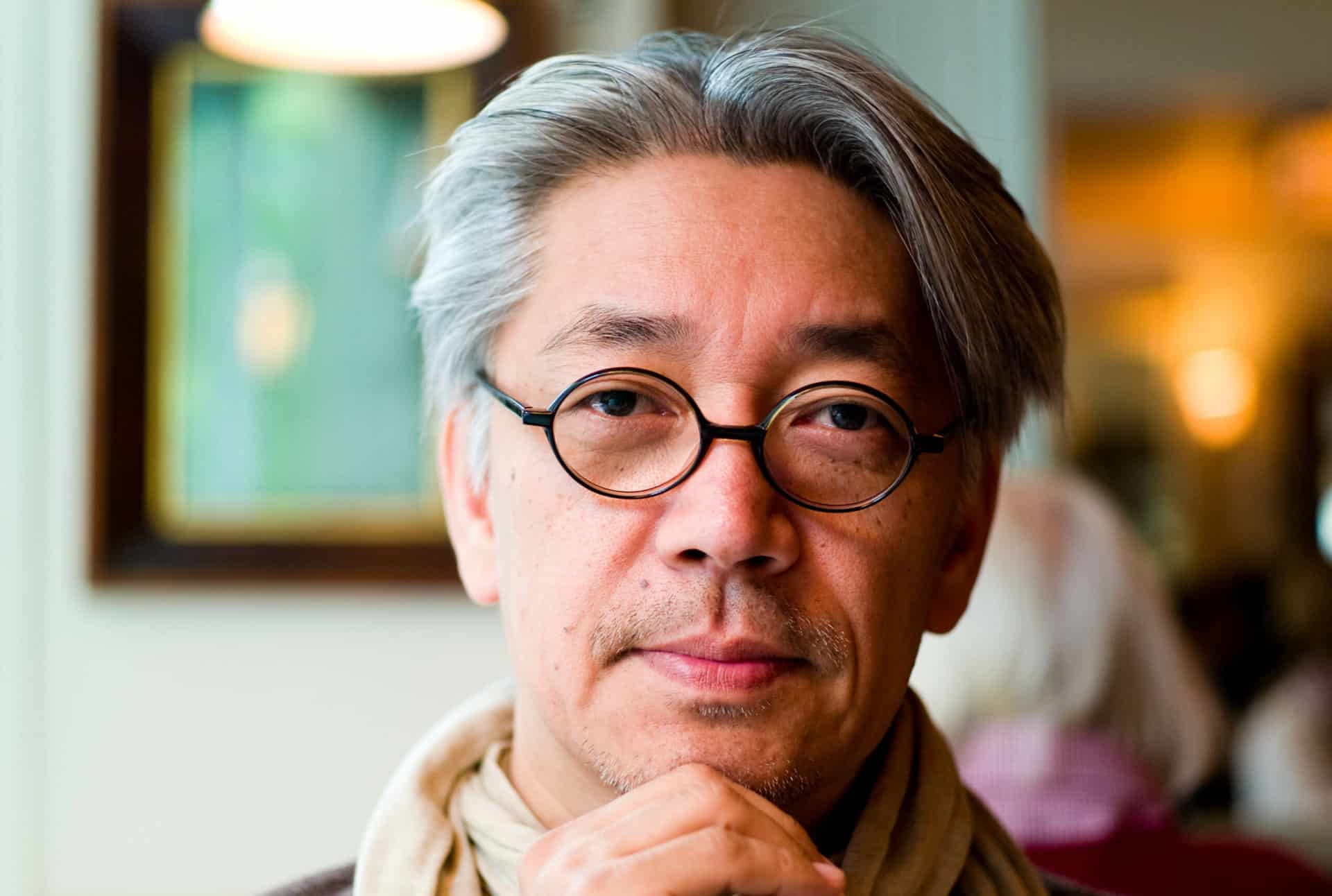

The woman in the center of Fig.5 (Ling Huang) appears to have greater authority as her jacket suggests she is Taoist clergy of some sort. Her other authority comes from an allusion another film she appeared in, the found-footage horror film, Incantation (Kevin Ko 2022). The film features a woman suffering the consequences of breaking a religious taboo six years previously on the grounds of a Buddhist-Taoist-Hindu syncretic mystery cult. Ling Huang plays Sister Hsiu, a religious social worker helping the woman after she regained custody of her daughter (Fig. 7)

Fig. 7. Ling Huang as social worker in Incantation.

When Sister Hsiu attempts to pass on a talisman with the daughter's name in it to protect her, the malevolent deity of the cult exacts a terrible punishment (Fig. 8), reinforcing the grim fate that might be in store for a reluctant ghost wedding groom.

Fig. 8. Sister Hsiu punished for defiance.

Wu indeed suffers the consequences of his refusal. He dodges a refrigerator that fell from a window only to be hit by a truck (Fig 9). The cast on his arm (which remains on during his first encounter with his ghost husband) suggests the relation of the film itself to the excess meanings it conjures without owning: a hand continually pointing at something without the person's control or consciousness of it.

Fig. 9. Wu under the curse.

Returning to work with multiple injuries, he is demoted and transferred to a minor police station. But the decisive moment came when a gun declared empty fired a bullet that ricocheted and came within millimeters of castrating him. The close-up of the near miss is another focus on Wu's “bathing suit area” (Fig. 10-11).

Fig. 10. Wu's near castration and the camera's lurid gaze at his backside.

Fig. 11. Gazing at his almost-demolished crotch, Wu decides to marry.

The wedding ceremony is elaborate and the aunties rejoice, even ignoring the vain attempt of Pang-yu's father (Tsong-Hua Tuo) to stop it. From this point I will use the names Wu and Pang-yu call each other, Ming-Han and Mao-Mao, respectively, in keeping with the involuntary intimacy that the wedding instigates. The procession guides both grooms back to Ming-Han's apartment and lays out Mao-Mao's favorite clothes on the bed.

I really enjoyed this close read of “Marry My Dead Body,” a film that wears its homophobia like an ill-fitting suit (which perhaps it always is). This essay does a great job of showing how Cheng Wei-hao uses the suggestion of queerness only to withdraw it. Its erotic promise always devolves into playfulness, the perpetual “just horsing around “ mode. It doesn’t merely play peek-a-boo with sexuality, but does the same with its genres (ghost /romance and police comedy)—which are only ever pointed at, and even then, quickly discarded. It’s a spirited, “messy,” but strangely charming film, as the essay points out, drawing its poignancy, in part, from the fact that it delivers on nothing it claims to promise. The scene in which Ming-han asks how to pick up gay men suggests the central role of narcissism at the heart of heterosexuality. Even the strange scene of Mao-Mao being crushed in the front seat of the police car seems worthy of analysis. But this essay importantly gets the ball rolling…

Thank you, Adam!