After the wedding party leaves, Ming-Han's uneasiness grows seeming to feel a gathering presence. When his soap slips out of his hand in the shower, he becomes even more fearful. “Drop the soap” is a phrase used to refer to the position one assumes in retrieving the bar that renders that person vulnerable to sexual assault, in prison, for example. Ming-Han seems to have that very much in mind has he stretches his leg out toward the soap without bending down (Figs 12-13).

Fig. 12. Ming-Han has dropped the soap.

Fig. 13. Ming-Han carefully stretches one leg toward the bar of soap, remaining upright.

Suddenly Mao-Mao appears on the shower floor directly underneath the Ming-Han's near split, and makes a point of noticing the view (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14. Mao-Mao gets a ghost's eye view of Ming-Han's nether regions.

He then appears nude standing behind Ming-Han, saying coyly, “Aren't we showering together?” Mao-Mao is clearly delivering these lines ironically, playing on Ming-Han's homosexual panic and his homophobic presumptions that gay men are predators. Having had enough of Ming-Han's tantrum, Mao-Mao attempts to calm him by explaining he never wanted the marriage. When the priest asked him before throwing the divination blocks, Mao-Mao had said “no”, but the blocks bounced off his father's shoe, resulting in a false “yes”. This reassurance doesn't work on Ming-Han, however it furthers the pattern of the film of asserting homosexual desire then denying it as a pretense, a pattern first established by Ming-Han in the arrest in the gym. Even the marriage itself is a Catch-22. At first it seems that it could function to make Ming-Han gay, but actually it renders Mao-Mao's homosexuality moot. But I would like to slow down, and take Mao-Mao's joke literally, to appreciate the real significance of the sexuality of the encounter denied.

Mao-Mao's view of Ming-Han is far more intimate than one would get in a locker room or shower, or even most medical examinations. His eyeline ends directly at the most secret stretch of the male body: from the scrotum through the perineum to the anus. The normative heterosexual male would feel doubly under threat: first the knee-jerk fear of penetration; most important, however, is not the unlikely event of rape but the eroticization of that region. Straight men have admitted to questioning their own sexuality when this occurs even within heterosexual encounters. Mao-Mao's gaze raises the possibility of alien, destabilizing sensations.

If we see Ming-Han as a single individual, this crisis remains on the level of micropolitics; however, if we see him as an agent of the state responsible for acts such as the raid of the gay men's party in 2004, it takes on macropolitical dimensions: delegitimation through sexualization.

Such an intervention, in fact, has occurred in entirely different contexts. In 2007, Dr. Ambarish Satwik, a surgeon specializing in vascular and endovascular medicine, published Perineum: Nether Parts of the Empire (Fig. 15). The book consists of several portraits of actual colonial rulers, representatives of the British Empire in late 19th and early 20th Century India, but fictionalized and entirely focused on the area of the body Mao-Mao scrutinizes in the scene under discussion. These vignettes detail with medical precision the rulers' various deformations, illnesses, sexual predilections and mishaps, entirely sabotaging the self-serious legends of these figures.

Fig. 15. Undermining the British Empire below the belt.

Finally, let us consider the scene cinematically. The mystique of a film derives in part from the way it orchestrates the seen and the unseen. We see Mao-Mao looking and can deduce what he sees but we don't see it. That division begins to construct in the spectator the intimacy between Mao-Mao and Ming-Han before either of them consciously experience it. But complicating this further, recall we are now taking the “joke” literally that had already been dismissed in the rhetoric of the film, since Mao-Mao denies any attraction to Ming-Han after this act of looking. This is why I call a recurrent pattern in the film, peek-a-BOO! eros. Sexuality appears suddenly, like the jump scare of a horror film, yet vanishes (is withdrawn/denied) as soon as it appears. On the other hand, the film is a record and what is denied remains there, like the repressed wish in the unconscious.

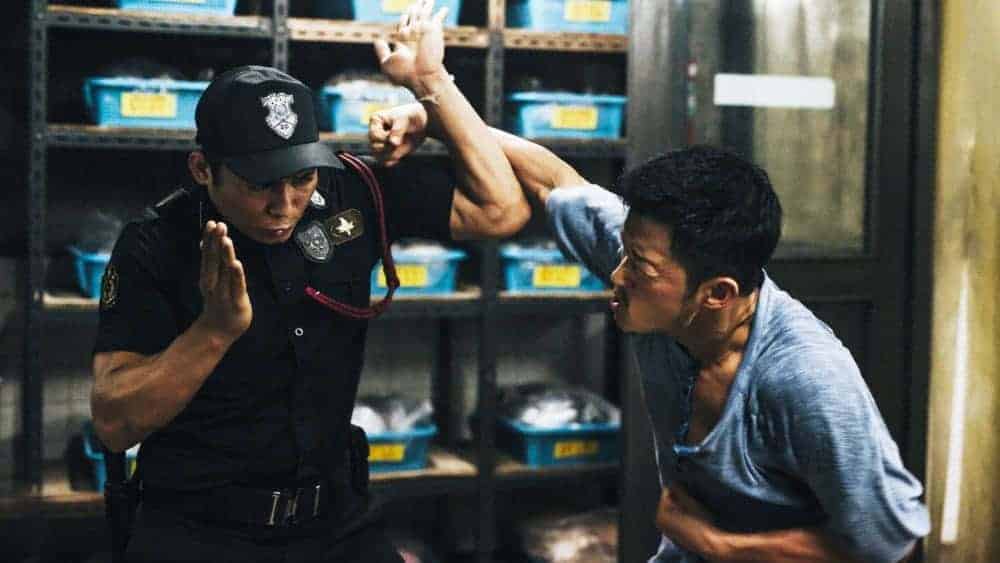

The next peek-a-BOO! event comes almost immediately at the close of the shower scene. Ming-Han repeatedly called Mao-Mao a gay slur. After given three chances to change his language Mao-Mao had enough. He possessed Ming-Han's body and sent him out in the street to dance naked (Figs. 16-17).. Ming Han immediately caught the attention of a police officer (Kwan-Ting Liu) who begins to chase the exuberant nude but stops and watches as Ming-Hao performs an impromptu pole dance, which the officer actually praises (Fig. 18).

Fig. 16. A Cop (Kwan-Ting Liu) gets an eyeful from a naked Ming-Han.

Fig. 17. Mao-Mao dances Ming-Han's naked body on the street.

The pole dance is particularly blatant in that “Ming-Han” deliberately flaunts the area of his body that Mao-Mao had seen accidentally. And he exposes himself to a fellow police officer (Fig. 18), but beyond that, to the actor Liu Kwan-Ting, one of the most celebrated and gifted actors working in Taiwan film today. Indeed, his presence in the film marks a status upgrade, working against the rather broad comedy (including very unfunny body shaming jokes targeting Ming-Han's hapless gay partner) and obvious action scenes that harken back to pre-Taiwan New Wave popular film. When the cop says of the pole dance, “That's pretty good,” it's also Liu as representative of serious cinema giving the film's messiness a thumbs up.

Fig. 18. Ming-Han gives the cop a complete show.

Liu Kwan-Ting's witnessing also has an intertextual dimension. In Classmates Minus (Huang Hsin-Yao Huang 2020), Liu wowed audiences and critics alike with his complex and poignant performance of a man with a severe speech impediment who made a living designing and building paper houses for Taoist funerals. At one point in the film, he is visited by the Lord of Death and looks on with him as the Lords emissaries make a procession through aisles of the man's exquisite ritual mansions (Fig. 19). Thus the cop is a special witness on several levels.

Fig. 19. Kwan-Ting Liu at the vanishinpoint observes the emissaries of death Classmates Minus (Hsin Yao Huang 2020)

Within the logic of Marry, however, this display is another example of a sexual assertion immediately denied. It is at once Ming-Han and not Ming-Han exposing himself in the nude dance. And although Mao-Mao is now literally inside Ming-Han, the sexual suggestions this holds are entirely ignored. And even though as a gay man, Mao-Mao can see the sexual allure of Ming-Han's body and manipulates it to announce it to others, he is motivated not by his own sexuality but from a need to punish Ming-Han for multiple insults.

Often the denials of sexuality are undercut by the camera itself. In one scene Ming-Han emerges from the shower room wearing only boxer shorts (Fig. 20).

Fig. 20. The voyeuristic camera follows Ming-Han's boxers

The camera zooms in on them and follows them as Ming-Han walks past Mao-Mao who gazes at them too and immediately shouts, “Take off that underwear!” a command that immediately sounds sexual. But he is complaining about the ghastly style that hurts his sensibilities. Just as that issue seems closed however, the image of a small dog on the boxers catches his eye. This triggers an even more extreme close-up of the shorts (and Ming-Han's crotch) while the film's narrative takes the sexual nature of the shot away by identifying the image as reminding Mao-Mao to have Ming-Hao rescue his dog, Xiao Mao, from foster care (Fig 21).

Fig. 21. Mao-Mao sees the dog. The camera holds a close-up on Ming-Han's crotch.

The article continues on the next page

I really enjoyed this close read of “Marry My Dead Body,” a film that wears its homophobia like an ill-fitting suit (which perhaps it always is). This essay does a great job of showing how Cheng Wei-hao uses the suggestion of queerness only to withdraw it. Its erotic promise always devolves into playfulness, the perpetual “just horsing around “ mode. It doesn’t merely play peek-a-boo with sexuality, but does the same with its genres (ghost /romance and police comedy)—which are only ever pointed at, and even then, quickly discarded. It’s a spirited, “messy,” but strangely charming film, as the essay points out, drawing its poignancy, in part, from the fact that it delivers on nothing it claims to promise. The scene in which Ming-han asks how to pick up gay men suggests the central role of narcissism at the heart of heterosexuality. Even the strange scene of Mao-Mao being crushed in the front seat of the police car seems worthy of analysis. But this essay importantly gets the ball rolling…

Thank you, Adam!