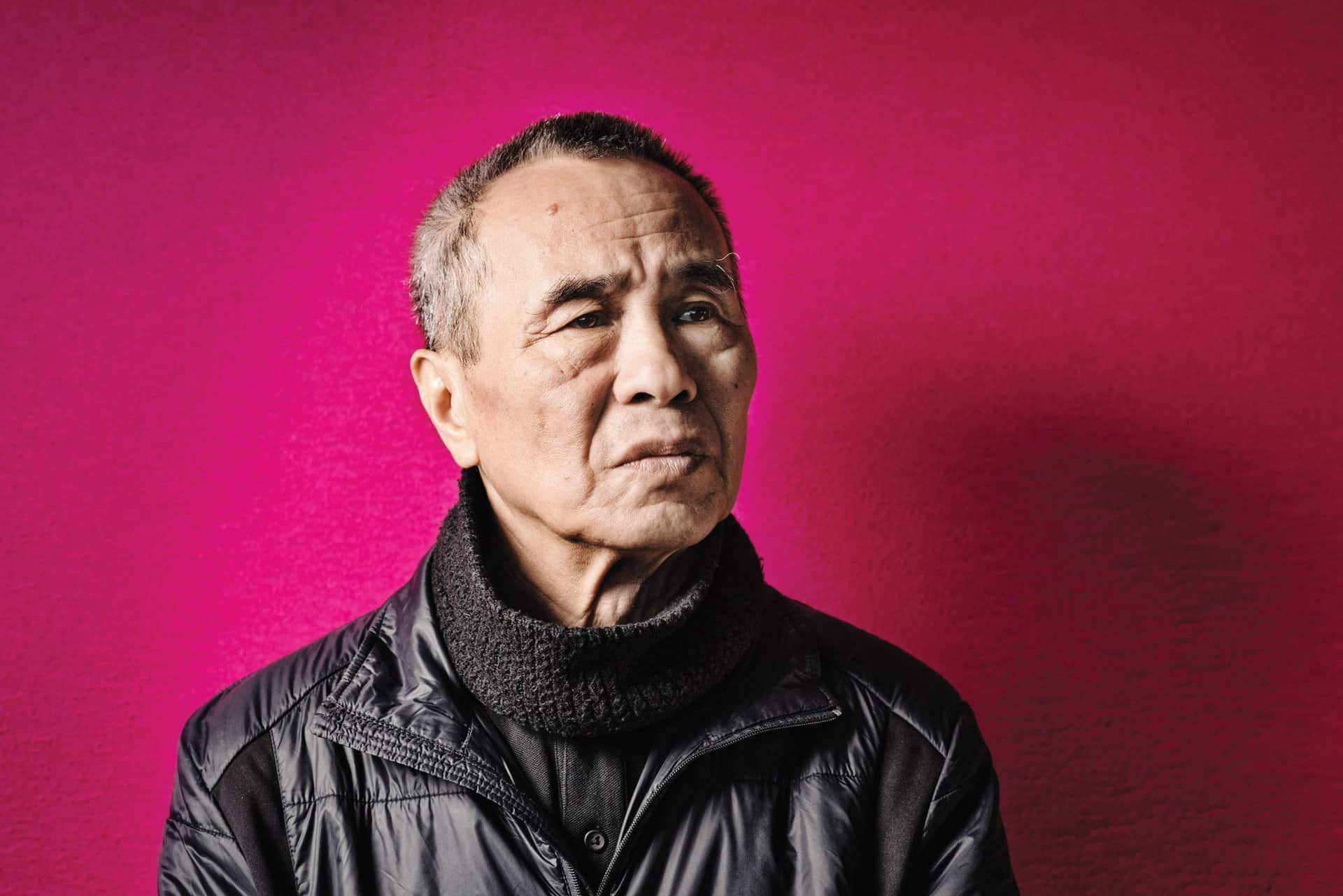

Jacob Wong is the Director of HKIFF Industry of the Hong Kong International Film Festival Society (HKIFFS). He is also the Berlin Film Festival's Delegate for Chinese-language cinemas.

On the occasion of his presence in Qcinema, we speak with him about HKIFF and its various streams, its financial and audience details, the changes the festival and cinema have undergone, his work with Berlin and Locarno, streaming services and the future of cinema, and the filmmakers he considers that stand out.

How would you describe the situation of the Hong Kong Film Festival?

The festival now has two streams officially, one stream being programming, the other stream being industry, practically the screening and all the non-screening activities. For many years, the film festival has been running some industry initiatives, the Hong Kong-Asia Film Financing Forum (HAF), which is entering its 22nd edition and then there are some little things popping up once in a while.

When you say little things?

Co-productions and foreign sales for example. We would invite Chinese companies, to make films with them, with the actual function being that they provide the funds and we the filmmakers, in an endeavor which started with a bundle of short films. Then we started doing it for a number of features, also with Chinese companies. After the films finished, they told us if we could try and sell those films for them. So we started working on those films regarding foreign distribution and we thought we might as well do it for other people. I think this was in 2005 or 2006, all these little so called industry activities or non-screen activities were put under the umbrella of the Industry Office. So now the Industry office has the following initiatives: In March, there is the Hong Kong-Asia Film Financing Forum (HAF. HAF has two streams: in development and work-in-progress. In May, we selected five projects from the work-in progress initiative and brought them to the Marche in Cannes, under the name “Asia Goes to Cannes”. I think there are a few festivals that do this, collaborating with the Marche and we are one of them.

Are these films only from Hong Kong?

No, the project market is open to everybody. Usually, there are more or less confined to projects from this part of the world, just because we don't have the money to fly people over, from Argentina for example (laughter). In late August, we have a film lab which runs for five days. At this moment, the projects are limited to Chinese language ones. Other than that, we do, as I mentioned, co-productions and foreign sales. These are the things the industry segment of Hong Kong FIlm Festival Society organizes. On the screening side, there is the so-called flagship festival, HKIFF. It takes place in March-April, over Easter. Over Easter because Hong Kong has Easter Holidays. It allows people to go and see films on four consecutive holidays. In August, there is a smaller festival, which is called the Summer Festival. It runs longer but has fewer films and the fare is lighter because it is summer. We also run the retrospective program, where films are played over the weekends, because nobody comes during the weekdays. In a nutshell, those are the activities of the Society, screening and non-screening. So it is a yearly operation, we have things to do to keep everyone busy.

How is the situation of the festival, financially?

The funding comes from the government entirely. The smaller projects in the industry section come from the people who are working with us, the people involved in co-production for example, they pay the budget and they pay us a fee. Foreign sales, since we mostly focus on arthouse films from this part of the world, obviously do not sell very well. We don't make much money, any money actually, but it doesn't cost anything.

In terms of audience, how was this year?

The audience, like most festivals, is shrinking. I think the festival sold around 100,000 tickets which is not a lot in a population of 7,500,000 people.

What part of the budget comes from tickets?

A third I think. I am not sure though. That is actually the ideal: a third from the government, a third from the audience, a third from sponsors. But there are fewer and fewer sponsors, so the government share is much larger. But it is not a very expensive operation.

And how many people are working for the festival, the core team?

The core team is around 30 people, because we have the retrospective program, which requires people to operate throughout the entire year.

Could you define the purpose of the festival?

It is simply stated as promoting film culture in Hong Kong. It is an old festival, it is going to be 50 in 2026. It has been through several stages. It was a very important window for mainland Chinese cinema in the last century so for the fifth generation of Chinese filmmakers, the festival functioned as a window for them, for the outside world. Chen Kaige's “Yellow Earth” premiered in Hong Kong for example. In the years before China opened up, it was a meeting point for filmmakers from China and Taiwan to meet. Those were the days when everybody came. All of a sudden, people became infatuated with Hong Kong cinema, the action movies and Wong Kar Wai, and so Hong Kong became a place where people came for the festival. That was before the FILMART. So we came up with publications on Hong Kong cinema of some significance for film researchers. We still do this but we are running out of people (laughter)

This is the most significant change you have seen through your years in the festival?

Yes, and then in the older days, film festivals were only of interest to very few people. Unlike these days. There is even a cottage industry of people writing books about film festivals. My sister wrote one, the first one actually. In those days, outside of Europe, no one gave a dime about film festivals. In 1996, we showed about 20 films. The festival also went through changes that were imposed from the outside. Things have changed, HK cinema is not what it was and there are a lot of film festivals coming up and something called ‘premieres' (laughing) That is a major shock for us, that film festivals would compete for premieres. In the older days, we never had to worry about that. We showed films, of course we did not show films that were commercially released in Hong Kong. Other than that, we could pick anything. Suddenly, there is competition.

How long have you been with the festival?

Too long! I started in 1991 if I remember correctly, as an English editor; I wrote the blurbs and did the catalog. I think it was 1997 when I started programming and then I think it was 7-8 after that I left programming and focused on the industry side of the festival.

Why would you say the decline of Hong Kong cinema happened?

Hong Kong never had a big population, and during the height of the glory years in the 80s, the population was around 6 million people and the industry produced 300 films per year. That is not reasonable. When something unreasonable happens, it is either a disaster or a miracle. In HK's case, it was a miracle, but both miracles and disasters soon come to an end. Because of the size of the population, which was so small, for a film to become really profitable, it had to be exportable, so Hong Kong movies, even those from the 50s were exportable products, they were exported to SE Asia, largely to the Chinese community. Well before HK cinema became known as HK cinema, there were Cantonese movies, they were very low budget, working class movies. Some of them were very good but unknown to the outside world, but they were still exportable products.

During the Glory Years, a lot of films were exportable and this is how the film companies made their money, locally as well as from the outside world. Japan and Korea were the biggest and most important markets. Especially in Korea, people a little younger than me grew up on those HK movies. And then the decline took place. The reason is quite obvious, the products were not good, so people stopped buying. Then, with the opening of China, with its 1,4 billion people, it would be unreasonable not to have a film industry. So China started producing a lot of films and China started having a lot of money and so the veterans, the people who were more experienced, all started working in China, especially when they want to make big budget films.

We have a younger generation of filmmakers and with government support, a lot of them were able to make their first film. Government support could be generous, the most you can get is more than one million US dollars. Most people get about half a million US dollars and with that and actors and crew being willing to take a cut in their pay, you can make a film. However, a lot of them are first films and most or all of these people who were able to make their first films with government money were not able to go on, because after you make your first film, you are already a professional film director and people judge you full effect. And there isn't' an industry, films are not really getting produced, so they have a hard time making their second film.

Check also this article

How many films does HK produce now, per year?

About 50, which I think is quite normal for a city of this population. Switzerland is about 8 million people, they make a lot of documentaries and make two fiction features a year.

Is there a star system any more, would you say?

No, there isn't one any more. There are stars but they are not getting any younger and they mostly work with Mainland Chinese productions, major films that cost millions.

Do young people go to the cinema in HK, particularly for local movies?

They do, but it is not enough. The older people don't go. A situation that is prevalent in Asia actually, I think. Only younger people go to the cinema. In Japan, of course it is the other way around, only older people go to the movies, especially to film festivals. In Europe, the film festival goers are a little older than the audience in this part of the world, which are the prevalent 18-25 age group.

Can you tell me a bit about your cooperation with Berlinale?

I worked for them as a scout. Actually, I started with Locarno and then someone asked me if I could do it for Berlin too. I said yes, because there was no conflict between the two festivals, considering when the two run. Then I left Locarno, almost 20 years now. In the beginning, I was responsible for Asia and eventually, a little later on NE Asia, what we call the ‘chopstick countries' (laughter). Hong Kong, Taiwan, Korea and Japan. Eventually, they downsized me so now I only do Chinese language countries. I think this is a lot better because my work is in China, the project market too, and there are a lot of Chinese projects. I think, among all these Asian countries, China is the most vibrant. It is a big country, there are a lot of people, it has lots of issues, and you have enough people who want to speak about those issues and yet enough people to want to make money making movies, and therefore, lots of movies and also creative energy in movies. Korea is going the other way, into series, Japan has been too rich for too long; except from one or two directors, the films are not particularly exciting.

So, having issues as a country is good for cinema?

No, if you are mainland Chinese for example, you always have censorship issues. You live with them and you manage them. The Chinese are very pragmatic people, from the outside and if you only read the mainstream press, life must be very hard. Yes and no, there are issues you need to be content with and that's the reality. You deal with them as best as you can. They are ingenious in that regard. Of course, there are times that are worse than others; during the past 2-3 years that was really a tough situation. People complained, older people complained more. During the pandemic, I was in China for 2-3 months a year because going in required 21 days of quarantine so I wouldn't just stay a week. I averaged a film every day, a new film to look at. There is a lot of creating energy, if the product is good or not is another issue; people are making films. From the very inexpensive one to the major blockbusters.

Are there any names that stand out for you in Chinese language countries?

From the younger generation, the people that stood out, who are better known to cinephiles, are two individuals from China. Wei Shujun and Qiu Young, both of whom have been to Cannes. I just saw Qiu Young's first feature and it is very good. Qiu Young works very slowly, Wei Shujun works very fast. So after this year in Cannes, he already finished another film, which is called “Dreams of Youth” I think, that is the literal translation. Qiu Young works very slowly because he wants to do his own thing, while Wei Shujun is more flexible (laughter). The mainstream directors on the other hand, are very localized, they make a lot more money but their films don't travel

What is your opinion on streaming?

Streaming is a reality that is going to stay with us, it is not going to go away. The mainland Chinese are very smart to keep the Americans away. They would really destroy our industry like they are doing in Korea. Technological advancements throughout history areirresistable, so filmmakers will have to learn to live with streaming, will have to navigate with those major companies. Moving images are always going to stay with us, movies I am not sure. China is a big country that has been closed up for so long and suddenly became so rich, and is so open to changes. A lot of changes are going to happen over there because there isn't any baggage. Japan has a lot of baggage, Western Europe has a lot of baggage, they have been rich for so long and they are not that prone to change. When you are young and poor and aggressive, changes are very welcome and that is happening with China now. In China, people are already experimenting with very short films on streaming platforms, which are very powerful. Some of the streaming companies can finance their own films, some have stopped financing and they are just buying. And the ones who are financing are experimenting with various forms, most importantly short films. The younger the audience is the more impatient they are with length. Streaming services would suggest filmmakers cutting up their films into very short segments and that way, you can attract more young audiences. This will probably have an impact on how films are made.

How do you see the future of the festival?

On the whole, not so bright. There are some issues with the quality of films made for festivals nowadays, they seem more like literally novels. Technically, they are all very good but they tend to be forgettable. The glory days of cinema, as I knew it when I was young, might be coming to an end. Like literature or poetry, which is something that might be happening to cinema as an art form. If this changes, festivals will also change. The big festivals like Cannes, for example, are an exception, but other festivals, in a lot of places, are having trouble attracting sponsors. Sponsorship has changed over the years too. When I started, sponsors would come because they liked what you do, and they wanted to support you. Nowadays, sponsors are advertisers, they want something back right away. “If I spend this much money, what will I get, and if I give you this money, what will you give me back?” This is the way they operate now.