by Patrick F. Campos

For the personal filmmaker, a diary of moving images is an unfolding promise—sense and story, thought and figure, advancing toward an open form wrought out of process and experience, which in time becomes a chronicle of moments and a keepsake of what once was. For an activist, a refugee, an exile resisting a military rule that extinguishes records, evidence, and lives, it is also a witness—not least for the future.

The weight of years of confrontation between film exposé and surveillance has been borne by the cinema-loving Burmese people for over a century now. Under British rule, which had earlier censored a genre movie hinting that the dominated native could actually fight back, Myanmar's first film in 1919 was an incendiary newsreel documenting an independence advocate's funeral. Later, despite the strict censorship rules of the colonial government, students from Rangoon University risked their lives to produce “Boycott” (1937), featuring real-life revolutionary Aung San and other young nationalists who had recently launched a strike. Aung San's fiery speeches were subsequently filmed by A1, Myanmar's pioneering film company, and shown in cinemas.

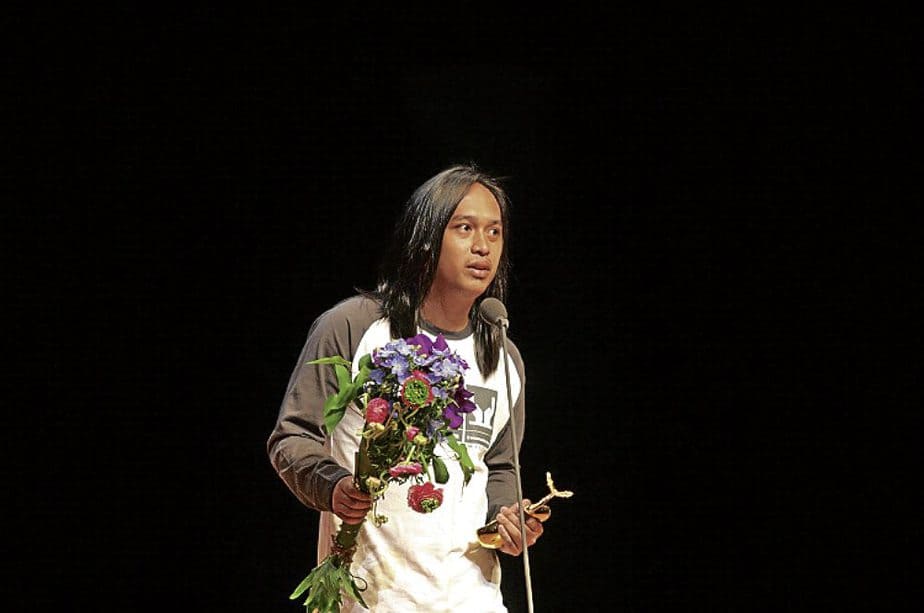

Seven decades after, this time under the 40-year-old Tatmadaw (military) dictatorship, documentarists served as harbingers of the oncoming Saffron revolution (2007-2008) and eventual democracy (2011-2012). These young filmmakers sought only to present the lives of ordinary people, but the situation was so onerous that acting on this impulse was considered subversive, especially as documentary footage illicitly circulated abroad insinuated the military's vulnerability. Thus, the artists' work of documenting disaster aftermaths, land confiscation, political imprisonment, and other issues framed through the everyday was itself heroic, performing the duties of an absent free press and amplifying the people's voice, despite the artists being under threat of state reprisal.

Check also this video

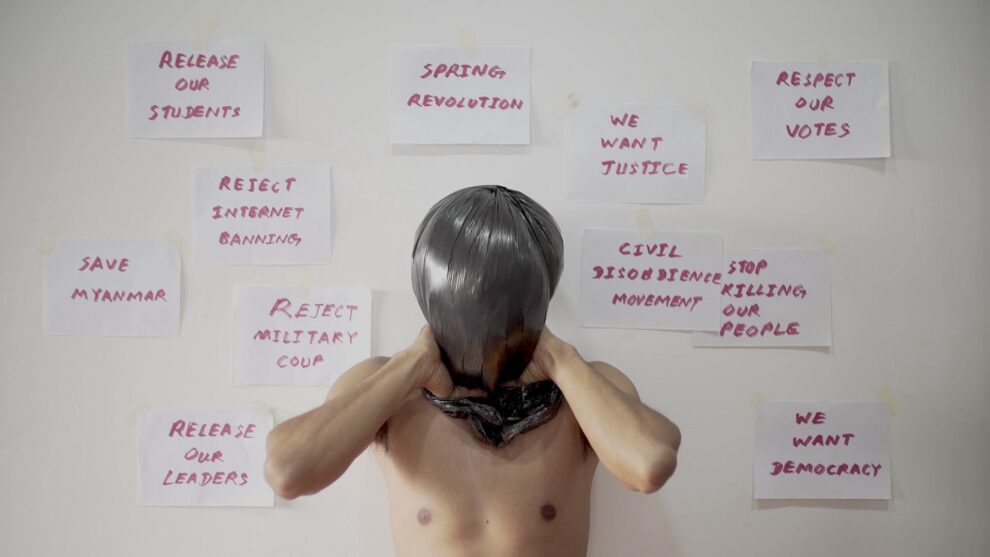

Two years after Myanmar's cinema centennial and after only a decade of fragile democratic transition, as the world was reeling through the pandemic, the Tatmadaw staged another coup d'état in 2021. The Myanmar Collective and Ninefold Mosaic—composed of anonymous artists and activists, some in hiding at home and others now political exiles, who have risked all to fight tyranny—have continued the heroic tradition and taken on the responsibility of witnessing. Understandably, the generation that nourished dreams of freedom and the one that awakened to it felt betrayed. In “Myanmar Diaries” (2022) and “Broken Dreams” (2023), the collectives documented nationwide protests, civil unrest and disobedience, the rise of a people's pro-democracy armed revolt, and the escalation of one of the world's longest civil wars fought by ethnic minority groups in the name of self-determination.

In an unprecedented way in the long history of authoritarianism in Myanmar, enabled by portable digital cameras, smartphones, and social media, the filmmakers kept a vivid record revealed in arresting imagery of the military's savage repression of freedom, cruel brutality, and scrambling for hegemony in the aftermath of the coup. Two years later, thousands have been tortured, disappeared, and died—hidden from the world's view, as the Tatmadaw jailed and killed journalists, constrained the media, and tried to shut down the internet. Both omnibus films mourn and memorialize the casualties, loved ones, martyrs.

In this dangerous situation, personal filmmaking reverted into a risky, urgent, and furtive act of numbering one's days of survival. The moving image diary became a space for secrets and pseudonyms, not because it hid private desires but precisely because the aspirations and suffering of ordinary people under the military junta needed to remain resolutely public, shown constantly, everywhere, far and wide.

Unlike their immediate predecessors, who turned mainly to documentary practice to elude censorship and unveil reality in the aughts, contemporary filmmakers have turned to hybrid and experimental forms epitomized by the heterogeneous omnibus format out of exigency and resonating with current media culture. However, instead of exhibiting today's familiar narcissistic behavior while hiding behind avatars in a digitally networked environment, these filmmakers sought refuge in anonymity and transformed their heartbreaking first-person stories of the coup into a form of collective action.

Check the review of the film

The documentary impulse endures, but this time, through the diaristic mode—of assuming personas, clipping and journaling, collaging and assembling, capturing outbursts, drawing impressions, interpreting experiences, virtualizing dialogues, working through fear, anger, guilt, and trauma, praying and meditating. Remarkably, these features are decipherable in various degrees and configurations not only in Myanmar Diaries and Broken Dreams but also in a harvest of recent films, including “February 1st” (Momo & Leila Macaire, 2021), “Seeking Wombs for Rebirths” (Lin Htet Aung, 2021), “Undaunted: Voices from Myanmar's Resistance” (Aung Naing Soe, 2021), “The Altar” (Moe Myat May Zarchi, 2022), Page Number 23: Yangon (Than Lwin Nyein, 2023), “Along the River” (Maung Moe, 2023), “A Step to Home” (Kyi Zin Thar, 2023), “The Watchdog” (Eunt Maw Oo, 2023), “A Revolutionary Mother” (Akkhayar, Black Ghost, 2023), “My Notes to Spring” (Zero, 2023), “Rachel” (Nway Oo Ngal, 2023), “Karenni” (2023), “XYZ and then A” (Creatio, 2023), “Immortal Rose” (Moore Thit Sett Htoon, 2023), to name a few. Though not all of these are “pure” documentaries in the conventional sense, they incorporate nonfictional images and document intense subjective responses to historical moments being forcibly buried in silence and obscurity.

Contrary to the Tatmadaw's draconian efforts, the coup, then, becomes the condition, not merely the subject, that gives rise to a host of film diaries and documents. These works posit the presence of a witness, or a collection of witnesses, as though to say: “I was there,” or “I know someone who saw what happened,” or “My friend or family lost someone there, and this is why I know.” People, even in hiding, mobilize to produce sense and story, thought and figure, out of the terror, subjective versions of lived experiences that allow them to bear the dark days, as their accounts of what happened fuel them through and hopefully survive with them. However it ends, someone always survives to give a testimony or receive one. And the testimony itself is the foretoken of the dreamt of ending.

The collective labor of recording resistance and remembrance in Myanmar is vital for the world to see but especially resonant in Southeast Asia, where state terror seems ever-present while constantly being distorted in social memory and social media. Watching these films outside Myanmar and denouncing the Tatmadaw allows us to bear witness to our own situations and histories in our countries, even as we form alliances and forge solidarities built on personal diaries and shared dreams.

Patrick F. Campos is a Filipino film scholar, programmer, associate professor, and a member of NETPAC and FIPRESCI. This article is the curatorial note for the series of screenings of Myanmar films of resistance at the University of the Philippines that he curated.