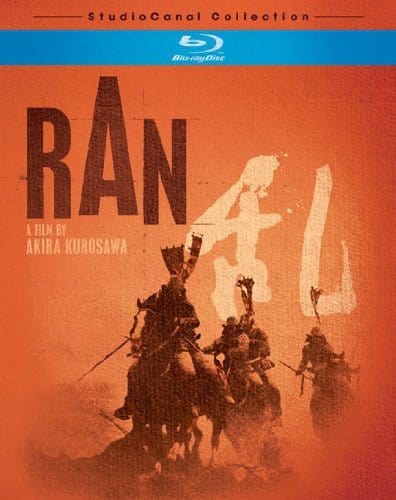

Akira Kurosawa's last epic was probably the most notorious entry in his vast filmography, since it was the most expensive Japanese film ever produced up to that point, with a budget of $11 million. It was also almost dropped for lack of funding, and the 75-year-old master lost his wife during the shoot, in an event that only stopped him for a day. Eventually, and after many ‘skirmishes' with the Japanese film industry, it received Oscar nominations for art direction, cinematography, costume design (which it won), and Kurosawa's direction, after a campaign started by Sidney Lumet. It is currently considered one of the greatest films ever made.

Buy This Title

on Amazon by clicking on the image below

In feudal Japan, Lord Ichimonji decides to divide his realm among his three sons. Taro, the eldest, will receive the prestigious First Castle and become leader of the Ichimonji clan, while Jiro and Saburo will be given the Second and Third Castles. Hidetora is to retain the title of Great Lord and Jiro and Saburo are to support Taro. His youngest son is against this decision, stating the obvious – that the three brothers have a thirst for power and their cooperation is almost impossible. Lord Ichimonji, however, considers his words an insult and banishes him, instigating a chain of events that results in a great war and his demise. In that fashion, Taro, who has all the power in his hands as the leader of the clan, is proven worthless; he scorns his father and sends him away and forces Jiro to do the same. The catastrophe is completed when the two brothers kill each other. Lord Ichimonji realizes his part in the drama and he loses his mind, but Saburo comes to his rescue. The one he deemed a traitor is the one who actually saves him.

Kurosawa was influenced by the William Shakespeare's play “King Lear” and borrowed elements from it. The common elements are:

1.The aging lord who decides to divide his kingdom among his three sons and banishes anyone who disagrees with him.

2.The two children that turn against him, with the third supporting him.

3.Both stories end with the death of the entire family, including the lord.

The bigotry and the futility of authority is the main theme of “Ran”. Family members end up killing each other for the throne, and family relations exist only in theory, since Machiavelli's dogma is the one that dictates every action, erasing any kind of respect or sentiment.

Kurosawa based his film on “King Lear” since the message he wanted to communicate about authority was eloquently portrayed in Shakespeare's play. The fact that this message transcends time and ethnicity becomes evident through the adaptation of a 17th century play in the 1980s, and the appeal Kurosawa's film eventually had on audiences. However, “Ran” is not just an adaptation of the messages of “King Lear” in Japanese terms. On the contrary, Kurosawa makes a pointed critique toward the emperor's authority in Japan, which, according to him, was the main reason for the way World War II ended for Japan and the consequences it had in Japanese society. In the 80s, the memory and the impact of the atomic bomb were still quite visible in Japanese society, and had resulted in a nihilistic and chaotic state of mind for many people. Kurosawa does not offer a solution, but instead aims in reminding the facts and the ailments of absolute authority, in order to help people think and to avoid making the same mistakes again in the future.

Kurosawa's tendency to present women in a very interesting light finds one of its apogees in “Ran”. Lady Kaede is the strongest female presence in the film, despite the fact that she remains a villain throughout the duration of the movie, and the fact that her actions all derive from her need for revenge against the Ichimonji clan, which Kurosawa justifies, at least to a point.

Kaede's character was based on the tradition of Noh Theatre, which did not focus on reality but rather fiction, and in that fashion, is one of the less realistic in historic terms, since the power she has was utterly uncommon for the era. Mieko Harada plays the part to perfection, in a role filled with extreme theatricality and a single-mindedness for revenge to the point where she shows nothing else throughout the film. To the direct opposite is the character of Lady Sue, whose presentation from Yoshiko Miyazaki makes an appealing character, particularly after her death. Both main females die, but the feelings deriving from their deaths are opposite, as Lady Kaede seems to have found vindication through the family's fate, and Lady Sue forgiveness, thus making her death more tragic.

In a rather original character for Kurosawa, Shinnosuke “Peter” Ikehata plays the court jester, a comical figure who ends up being Hidetora's last surviving servant. Despite the entertainment the character offers through his occasionally crude jokes and shenanigans, he also signifies the demise of his lord, who is left with none but a jester, the only character Hidetora actually saved.

No discussion regarding the acting in “Ran” would be complete without mentioning Tatsuya Nakadai's sublime performance as Lord Ichimonji. In the second role of the film influenced by Noh Theatre, Nakadai wears a mask resembling the ones used in the particular theatre, while his body stances also move toward this direction. Through this technique and his abilities as an actor, Nakadai actually becomes Hidetora, perfectly presenting the lord's declining psychological situation, from a dominant man emitting power, to one disillusioned about his mistakes, to a lunatic.