In her latest documentary “Onlookers”, the Japanese-American director Kimi Takesue takes a deep look into the phenomena of mass tourism in Laos, in a strictly observational, non-interventional manner, done in such a way that it makes us ask who are the actual observers and who is being observed. It is a work of visual beauty and warmth that doesn't pass judgements about anyone that appears in front of the lens. Life simply happens right in front of our eyes: the comings and goings, the selfie-taking tourists and the always busy locals who are trying to make the best out of the tourist invasion.

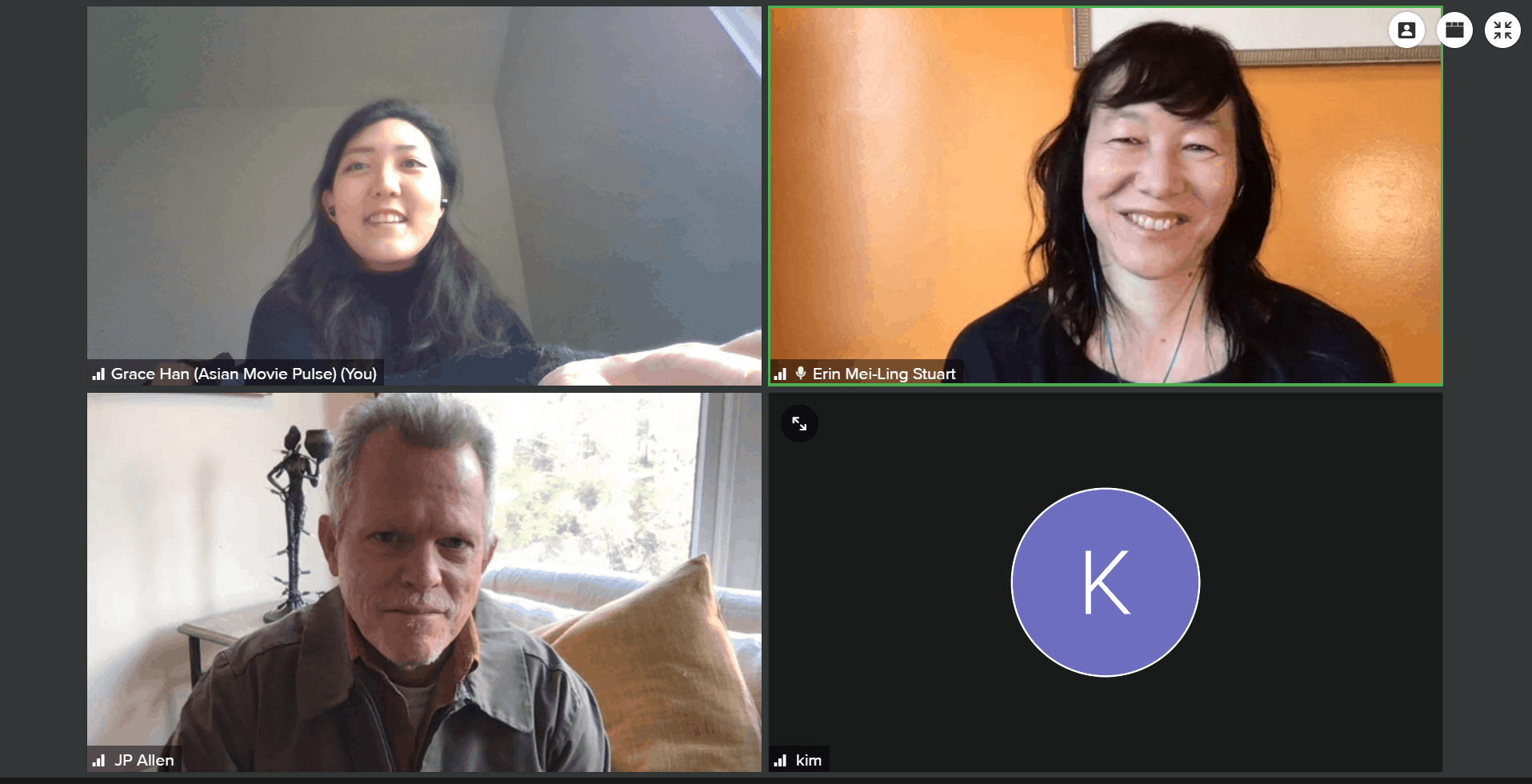

The film had its world premiere at the Slamdance Film Festival last year where it was awarded an Honorable Mention in the Breakout Features Competition. The international premiere at Cinéma du Réel followed, where it competed in the official selection. Many international festivals after, “Onlookers” opens in U.S. theaters on Friday, February 16th with the screening in New York's Metrograph as part of the series “Fire Over Water: Films of Transcendence“. Asian Movie Pulse took the opportunity to speak with the helmer about her creative process, being a “fly on the wall” and her never ceasing interest in cross-cultural encounters.

I would like to start this interview by asking you who the actual onlookers in your movie are? Tourists, locals, or maybe you?

I think that you answered the question. I appreciate your view on it. It was the key aspect of the film. It is pretty much about this circulating game, or the circulating perspective, and ultimately it is asking the viewer to reflect upon their own position as spectators, in terms of their own gaze. The way the film starts is about looking at this other culture. There is a shifting perspective, and ultimately that's being reflected on the audience about how we all are invested in the act of viewing. So, this is a film that is questioning all different aspects of observation and the different qualities and ways of looking, seeing and reflecting.

The stability of your camera creates a stage on which you let things happen. I guess that that the whole thing requires a lot of patience and time calculation in order to achieve the result we see in the film.

It is a kind of filmmaking that is so much about patience and my own investment in the place, being present and very much attuned to something unfolding. I am very interested in the interplay between naturalism and stylization in the sense that I am finding a kind of composition and some kind of frame that excites me formally. What's wonderful is that everything that is happening is just unfolding in front of me. I do not direct anything, I'm not asking anyone ever to do anything, so it is this kind of magic finding those moments when all of the elements cohere. It really is a feast because it is so much about aesthetics, and having everything in terms of the light and composition, the choreography and the movement that is big part of the film. Also, to have the color and the sound, everything working in a kind of magical synchronicity. I can't completely control it, but i am finding my ways. That's part of the process – being sensitive and in tune to these moments.

Check the review of the film

I am waiting, so I am recognizing and seeing patterns and possibilities, without being completely able to predict everything. For example, I might see a situation that is of interest, but facing the experience where the elements are not all there, and in some cases – patterns. A big part of this piece is about patterns of movement, and people coming and going in a certain kind of regularity. So, you could, on the one hand, be indecisive aboout shooting the scene because the lighting is not right and it's not gonna work because I need the picture to be beautiful, on the other hand, I can come back and hope that maybe that moment appears in the same way. At the same time, it's really hard to completely replicate it. It's never quite the same. So, it is part of the excitement because this is a very patient form of filmmaking, almost like the meditation in itself since I am alone, and there is no crew.

I think that this an example of filmmaking that is possible only as an individual because it is about landing in the surroundings in a certain way. I am not trying to hide my presence, but I am a quiet observer who is unobtrusive and unintimidating in that space. It is all about landing in and waiting. Any kind of external presence would be distracting for me. Otherwise I would have to think about the different understanding of time, or if I was wasting someone's time. I really like judging things on my own – how long I want to be somewhere and be in that moment.

Most of the tourists don't pay attention to your presence, but one becomes very much aware of it – the young man with the camera who took his time to make snapshots of the monastery and its vicinity in front of your lense. What is parfticularly intriguing is the clash between the traditional way of living and the modern way of intrusion into it, particularly in the footage shot around the Buddhist monastery.

I woud like to turn to your first observation in this question because that scene is reflecting a lot back to the viewer; you are conscious of the act of filmmaking, the fact that one is always in a certain ambivalence of what merits to be filmed. That's really what's being demonstrated – one person going through the entire process of decision-making. What should I film and what is worth photographing? You see that the young guy is kind of considering the situation. Maybe he feels compelled to be photographed. You can see his inner conflict being externalized: photographing and being photographed. But I also think that there is an obvious humor in it, the absurdity of life expressed: the pressure to be present, but also to document. A lot of that contradiction is part of the film.

Considering other aspects of filming, there are many open spaces, concretely in the case of monks you were asking me about. There is no sense of division between them and the rest of people passing through those spaces. You can just go to the temple where the monks are living. I was just enjoying being there because those are beautiful and fascinating open sites. You are obviously seeing the ways they become a spectacle and commodified, but you can still enjoy. I think that the film is looking a lot at that tension, and the fetishization of certain aspects of culture, the way they can be commodified, but also the reality of the seduction of difference. The monks, their rituals and attire are the cultural signifiers. If you are outside you can be taken by the aspects of that beauty.

I don't think that there is any easy take on that. The film is raising a lot of such questions, and trying to make the viewer aware of those complexities. But I am also trying to break down the mystification of the monks. You can see one of them smoking. I don't know if you caught that. You also see monks that are kind of bored. Actually, there are many different kinds of representations of them in the movie. And then at the end, for me the last shot is so powerful because on the one hand, it's “oh, all of these monks are the same”, and yet it's a really amazing example of different natures. You can see that they are not alike in character. They are all dressed the same, but you see all the little details, and the time allows you to just watch and be able to kind of appreciate all those distinctions. And that is so much what this film is about – getting the time and space to be able to appreciate all small details.

By watching your movie, one might guess your background as someone with a degree (among other) in Cultural Studies.

It's weird how we evolve in our lives, and how different interests form us subconsiously. I thnik that there are certain elements that are very defining in my perspective, but one of the strongest is my bi-racial background. As half Japanese and half American, I was growing up between Hawaii and Massachusetts in a very fragmented way. I had a very particular perspective as someone who is always an outsider, but who has also managed to kind of navigate spaces in terms of having to assimilate in some ways, never feeling completely part of a group. So, I really occupy this space on the margin as an observer, but I feel like I'm able to connect and integrate pretty easily with a lot of different groups. So, I think that what we see in “Onlookers” is that perspective. It's kind of both an outsider and an insider take on things, and that kind of fluctuation. In all my work, this has been consistent, because it's fascinating to look at tings that way. Even if I am addressing different kinds of subject matters, I often return to the basic theme of cross-cultural encounter. That really does come up in my work, also in my fiction movies. And that again is so much linked to my background and my personal experience.

What was the moment you knew that you wanted to become a filmmaker?

For me, it really was an extension of my academic background – Cultural Studies and Women's Studies. I wanted to expand on my theoretical interest in film. I was very much influenced by people who were working across academia and arts and film, like Black Audio Film Collective Sankofa from London who were looking into questions of identity and the politics of representation through a more theoretical lens. And then, my first film “Bound” (short, 1995) was more of a translation of certain ideas around exploring the cultural identity. I was looking at the Chinese-British woman on her symbolic journey to self-discovery, and at how an identity defined around the categories of race and gender can be both offering form, composition and structure, but also how it can become strangulating and take the position of oppositionality, where you are constantly defined in relationship to what you are opposing.

Pretty soon after, I made a decision not to be working in that way anymore. There were films like that before though, and many of them excited me. Ultimately, there was more about writing or the intelligence of the maker in explaining the work that I find more interesting than the film itself. But, I also wanted to be accessible. My work only requires some patience, and not some kind of insider knowledge. My challenge is how to bring in all of these levels of complexity that can meet the viewers and their points of entry. The aesthetics are very important to me, and that the film has something that is emotionally going on, as well as a dose of humor. There are also other conceptual foundations and sort of theoretical strands, but I never want to be didactic or heavy-handed, which is very hard to do. Sometimes my work gets mistaken for being simple, while in fact I think a lot of times that this is the hardest thing to achieve. Often, reducing things to a very simple form is extremely challenging.

I have to think of your grandfather's words in “95 and 6 To Go” (2016): “Kimi, you've got to get a job. Until you get your financing, you are just losing time”.

And I listened to him. I got my self a teaching job (laughs). One of the things that is interesting about my grandfather is the contradiction surrounding him. On the one hand, and I think that he is even talking about it, is that he was ultimately seeking a companion to take care of him, someone who takes the liking at same things as him, but who will cook and clean. On the other hand – he always had a strong need to be independent. My grandfather never encouraged me to get married and he always emphasized how I should take care of myself and not rely on anyone else. That's fascinating because he was so conservative and traditional his whole life.

Going back to “Onlookers”, it would be interesting to know how you worked with the sound, knowing that you are a “one woman orchestra”.

Miraculously, I didn't have much difficulty recording any extra sounds. It was remarkable that certain things have been recorded so well. I really just had an external microphone on the camera, and I had no boomer or such. I was usually at far distance from what I was photographing, and I also had an external recorder, but again it was all from the same position of the camera. Strangely, I was able to record all the sound with them, even the music coming from the loudspeakers of the truck that was collecting money for the temple. That was being recorded at that far distance. You have the karaoke music that is coming from a wedding, and that is being sung again from a far. It was kind of amazing what came out of it. The actual sound recordings are the foundation of my film, but I do enhance them.

There are lot of additional layers of sound that are included to make it more immersive, in terms of the ambience sound, introducing more birds and insects and other kinds of things. But I fundamentally like to work in a naturalistic way, and I do not like to stylize. It's a difficult choice, because you can easily start going into a more stylized place that offers an easier way to engage with the audience. A lot of people need a voice-over or music to engage, and those push a lot of films along. It's a big choice to remain faithful to naturalistic sound. I wanted it to be more subliminal and subconsious.