Emerging from the bustling streets of Beijing to the vibrant cinematic halls of NYU, April Yang is a student filmmaker whose journey is as compelling as her films. Her path began with the six awards winning teen mockumentary “NIGHT,” an exploration of human connection amidst the energetic streets of Beijing. As a female director, April consistently infuses her work with a unique perspective, delving into the nuanced complexities of female experiences and their familial relationships.

Unlike traditional filmmakers who follow the conventional path of film school education, April's journey is distinct. Until September this year, when she was set to enroll at the prestigious American Film Institute (AFI), she never had an “official” opportunity to be a student in a film school. The onset of the pandemic forced her to forego studying abroad and instead attend NYU Shanghai, a nascent institution without a film program. As an Interactive Media Arts student, she spent the past four years exploring every possible resource and filmmaking opportunity. April has charted an unprecedented undergraduate path, leveraging the NYU Shanghai network to pioneer her way as a film student.

As she approaches graduation in 2024, April finds herself at a pivotal moment, reminiscent of the beginning of her journey into the film industry. She has poured everything into her latest independent film, “Broken Finger.” This time, as a female director, her perspective is even more nuanced and daring, tackling bold and provocative themes—the intimate connections between pansexual women through sex. From the initial script draft to the week before shooting, she independently managed the entire production, showcasing her resilience and commitment.

Broken Finger

“Broken Finger” has received selection from 10+ worlds film festivals and will have its world premiere at the Toronto International Nollywood Film Festival in Canada soon this September. Reflecting on the inspiration behind the story, it dates back to three years ago when the pandemic swept across the globe. This worldwide event not only impacted grand themes but also profoundly affected individual lives on a micro level.

During the relentless lockdowns in China, April observed a societal phenomenon—the emergence of a people-pleasing personality predominantly among women. Perhaps it was the disappearance of physical social interactions, but social media at the time consumed all of people's attention. East Asian women, already part of an underrepresented group, experienced a significant increase in psychological manipulation and coercion (PUA). Women on these platforms seemed to derive their entire sense of self-worth from external validation.

This unequal, people-pleasing dynamic was even more pronounced in intimate relationships, something April experienced personally. In such a challenging social environment, East Asian women exerted themselves to become the ideal person in the eyes of others, especially their “lovers,” often neglecting their own identity. This background inspired the character of Wang Xiao in “Broken Finger.” She embodies April's experiences and the spirit and body of countless East Asian girls still navigating that lonely period.

Non-linear and Black-and-White Artistic Expression in BROKEN FINGER

April didn't want “Broken Finger” to be confined by the traditional three-act structure. She was influenced by her favorite and most respected director, Leo Carax, a key figure in the French post-New Wave movement known for his non-linear and experimental style. She aimed to create a film that seamlessly transitions between self-fantasy and reality, as people-pleasers are often those who willingly live in a dream.

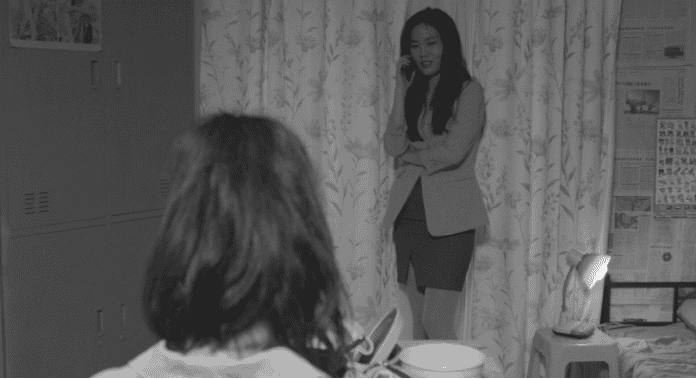

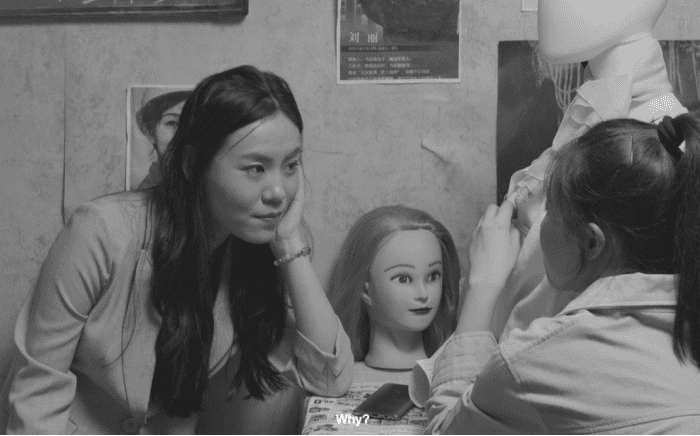

Hence, “Broken Finger” is divided into two parts. The first part, depicted in stark black and white, represents the real world, while the second part, vivid and hallucinatory in its extreme colors, represents a world so vibrant, it feels almost unreal. Audiences often ask her why she chose this form of expression.

April's response is always: “This is not merely an artistic choice. As Carax said, ‘I view black-and-white film as an independent art form, distinct from color films, and often more imaginative.' I want to guide the audience to see black-and-white and color as two separate worlds. As for which one is reality and which is fantasy, that's up to you to decide.”

The emotional connection between les women through sex.

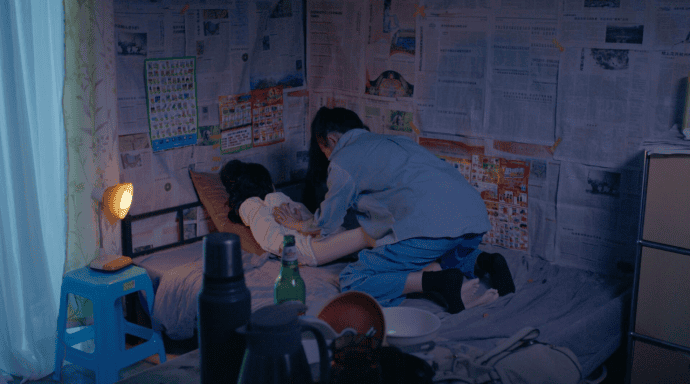

April was born in 2002, and she was only 21 years old when she began preparing and filming “Broken Finger.” The first scene of “Broken Finger” is a provocative seduction scene, and the second act escalates to a lesbian sex scene. When her producers and mentors heard about the concept and saw the initial draft of the film, they gasped and warned her that this was an extremely challenging project. They cautioned her that it would be very difficult to find willing actors, it would require a significant budget, and it might never be shown at Chinese student film festivals.

But April persisted. She bypassed traditional production routes and, much like her high school days, independently reached out to actors she had worked with before, sending them letters of inquiry. In addition to the help from the crew, she took on every vacant role herself. She even prepared herself mentally to step in as an actor if she couldn't find anyone willing to take on the roles.

Explaining why she chose this theme, April said: “In the East Asian context, and perhaps globally, there is a popular saying: to bring down a woman, you only need to label her as ‘the other woman' (mistress). This is a shorthand for the stigmatization and devaluation of women. A woman's strength, professional abilities, and social status can all be undermined by accusations about her intimate relationships. As professor Dai Jinhua aptly notes, “In a patriarchal society, the discourse on female sexuality is often a means of control and subjugation. Women are frequently reduced to their roles in intimate relationships, and their worth is measured against societal expectations of purity and loyalty” (Dai Jinhua).

“I believe that the ultimate barrier to forming a people-pleasing personality lies in the inequality of sexual power dynamics. It begins with relinquishing one's power in conversations, constantly seeking approval through words, and eventually leads to surrendering one's power in sexual relationships, physically appeasing the other person. This is the trajectory of how psychological manipulation (PUA) develops and solidifies. I want to shed light on this situation. In the final scene, Xiao's tears are meant to convey a crucial message: love is simply love—it cannot be equated with pleasing others. Pleasing others only leads to continuous self-sacrifice and harm. Just as Xiao broke through her own barriers and gave up everything, she still couldn't find the love she sought. Love should never be something one has to beg for.”

“When such dynamics are placed in the context of a lesbian relationship, where there is no inherent physical inequality, the psychological and emotional power imbalances become even more pronounced. The one who controls the discourse on sexuality is the real exploiter, not necessarily the ‘weaker' partner in the sexual relationship.”

Pre-Production

“Broken Finger” underwent 24 script revisions, totaling 70 hours of script discussions and a two-day full cast meeting. It's unclear what such data points signify in the preparation of a 13-minute short film. However, the actors remarked, “This level of dedication is unprecedented. We were surprised to learn that this story is original. It's the first time we've felt so compelled to contribute to a short film role, leveraging our life experiences to help April better convey her character. This story is truly unique.”

Production

April once had the idea of forming an all-female crew to shoot this short film, but given the current Chinese market and the tight production timeline, it seems that this is not feasible. During filming, aside from April and her executive producer, the entire crew consisted of male members. Thus, April insisted on all crew members signing a nondisclosure agreement specifically for the shooting of the second act, without exception. Additionally, all crew members were required to leave their phones in another room during filming. Her thoroughness aimed to protect the rights of her actors and provide them with a sense of security during production. At that time, amidst the notorious ‘Nth Room Case' scandal in South Korea, a poignant sign read, “One of my friends who has been reduced to ashes is still labeled as ‘XX University, XX woman' in some men's phones.” This underscored the necessity for her actions.