Seoul legend says that today's pigeons come from 1988. Apparently, someone imported a number of doves for the Olympics opening ceremony; however, upon release, no one could quite round them all up again. Resistance against the domestic authoritarian regime functioned in a similar way. Western ideas of freedom and democracy infiltrated the Korean peninsula; once released, they only blossomed. This coincided with the so-called “Miracle of the Han River,” where it became increasingly apparent that only a few would reap the riches of the many. Added to this, of course, were the traces of American neo-imperialism — first manifest in the military and now in McDonalds. As locals increasingly felt the pressures of the modern world, a protest culture was never too far out of reach. Korea, it seemed, would be embroiled in yet another decade of turmoil with no equity or resolution in sight.

Buy This Title

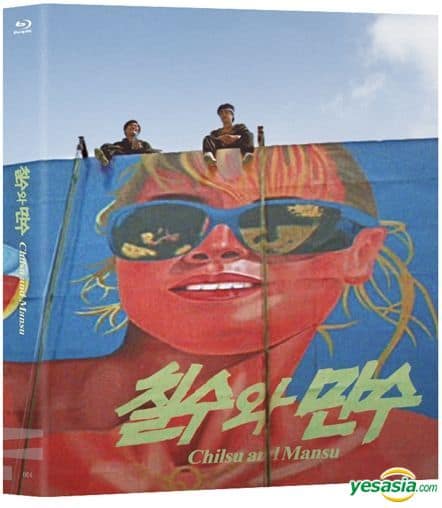

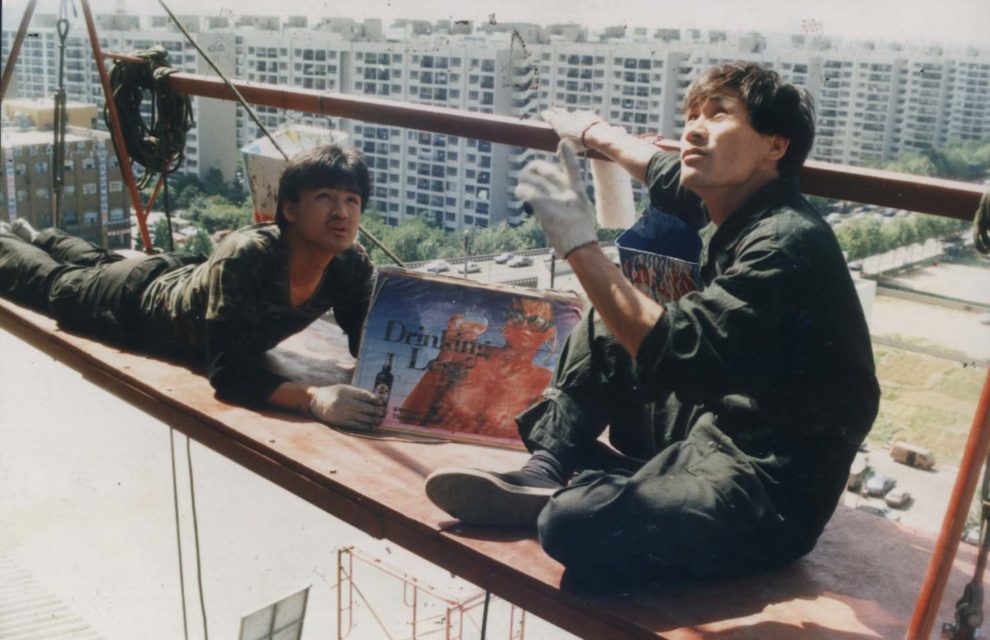

Amidst all this, Park Kwang-su released his directorial debut “Chilsu and Mansu”. In an era when most Korean cinema was explicitly sponsored or in favor of the state, “Chilsu and Mansu” suggested a bold alternative. Though the story begins lighthearted, the film's tone is largely disgruntled. Chilsu (Park Jong-hoon) is a lovestruck industrial painter with dreams of going to America. On the other hand, his alcoholic work partner and housemate, Mansu (Ahn Sung-ki), is incredibly disillusioned. He drinks away the days to forget his family's own Communist ties and his near-zero chances at social mobility. As these two blue-collar workers scrape by, symbols of Korea's US-dependent economic decadence — including department stores, Burger King, and even Rick Astley's “Never Gonna Give You Up” — feel like a stinging irony. It seems only natural, then, for the two to conduct their own revolt against the establishment… though not without consequence.

Watching “Chilsu and Mansu” today feels like a sharp reprimand from the past. Its mixed comedic-satirical tones depart from today's feel-good 80s nostalgia, marking a stunning contrast with 2015 hit K-drama “Reply 1988.” Here, a group of five tightly-knit friends witness how love and friendship supersedes wealth differentials in their cozy northern Seoul neighborhood. The blockbuster actors blithely clothe themselves in high-exposure camera filters and baggy clothes, blissfully unaware of the tumultuous political conditions down south.

In contrast, “Chilsu and Mansu” takes place in the heart of the political drama: in Gangnam, the site of the Olympic stadium, the symbol of Korea's economic revival, the south of the Han. The film unabashedly exhibits the two's modest conditions in Gangbuk (north of the Han River) compared to their spick-and-span employers and lovers in Gangnam. Their house has little to no furniture; their work clothes are made to sweat in rather than to stiffen. Chilsu regularly changes out of his work clothes to impress Jina (Bae Jong-ok), the girl of his dreams — and gets embarrassed one day when he discovers mid-chase that he's still in his standard camouflage ‘fit in the middle of an upscale department store.

Park Kwang-su's choice to film on-location further implicates the sheer geographic distance between the worlds of the working and middle class. Mansu's favorite pojangmacha (outdoor food stall) is based around Cheongnyangni, deep in the less wealthy neighborhoods of northern Seoul. Even Mansu's home in Oksu-dong — located along the periphery of the river's northern edge — is straddled between the two sides. The locations highlight the disparate economic zones but with no bridge in sight. (What an added irony now that Mansu's home marks one of the most recently gentrified areas of Seoul!)

Moments of poetry pepper the angry prose, however, in You Young-gil's camerawork. While the editing does much of the talking, the camera occasionally disrupts the rhythm with a mindless lingering. When Chilsu exaggerates his situation to flirt with Jina in a petit cafe, for example, the camera simply stares – and then gradually pulls back, as if to reveal the sheer ridiculousness of his lies. Other moments feel experimental, almost Brechtian. Chilsu looks over the edge of his old home and remembers the ghosts of his family's US military-stained past. A montage of women pass before his eyes, each looking up in askance before their goodbyes. The sounds of the city fall to a sudden hush as Chilsu attempts to muffle the echoing cries of his own history.

Sound escapes through the seams, however, demanding extra attention from the casual viewer. As obviated from the on-location filming and the presumably poor sound equipment, the dialogue (often recorded on-spec) blends into the cityscape. Even at the pinnacle of Chilsu and Mansu's standoff, they can barely hear their government officials below. Geographic distance again plays a role here: the voice of the individual drowns out in the city noise. The only sounds that truly override the narrative are the ones added in post-production — that is, the distinctly contemporary American music. It almost marks a parallel between the auteur and the studio. Foreign, polished, well-funded studio sound trumps the local workingman's gag. Despite the latter's struggle, the quality is basically incomparable.

Perhaps it is unfair then to compare “Chilsu and Mansu” to “Reply 1988.” The former functions as an artifact of its own time. It wrestles with the indomitable gaps in Korean society so easily painted over under the cheerful veneer of modernization. For those intimate with the city of Seoul, the movie presents a charming amble through the city's older streets' for those familiar with its moment, this epitomizes an icon of its era. All in all, “Chilsu and Mansu” — as a film, a political statement, and an artifact — still reminds us of the preciousness of free speech. It represents the trickle that became the flood: of how not just speaking, but hearing is of utmost importance today.

I love to read Grace’s article. Thank you so much for sharing your insight.