By Raghu Pratap

French-Vietnamese filmmaker Tran Anh Hung came to the cinema world's attention with his very first film – “The Scent of Green Papaya”: a glacially paced, aesthetically lush work set in 1950s and 1960s Saigon with a significant dose of political subtext that continues to find relevance even today. The film created waves among the film fraternity, winning two awards at the 1993 Cannes Film Festival including the Camera d'Or, a Cesar award for Best Debut Feature, and an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film in 1993. “The Scent of Green Papaya” forms the first of a triumvirate of films -referred to as Tran's ‘Vietnam Trilogy' which includes his later works: “Cyclo” (1995) and “The Vertical Ray of the Sun” (2000).

The movie takes place in two timelines, separated by ten years. In the first section, the film revolves around, and follows a young girl ‘Mui', who arrives to work at an affluent Vietnamese household in Saigon, in 1951. She is a curious and sensitive young girl, attuned to the sounds of the world, that of small insects, of trees and other minutest qualities of nature within the confines of the property: a two-storey house with a sprawling compound of green that serves to highlight the dichotomy of the space, of gender as well as class – where the family (wife, husband, three sons, and the grandmother) eat, and where Mui along with an older helper cook and eat. There is a conscious cinematic focus on the banal, specifically on everyday household chores as we see her harbour an inarticulate curiosity towards the papaya tree outside her window.

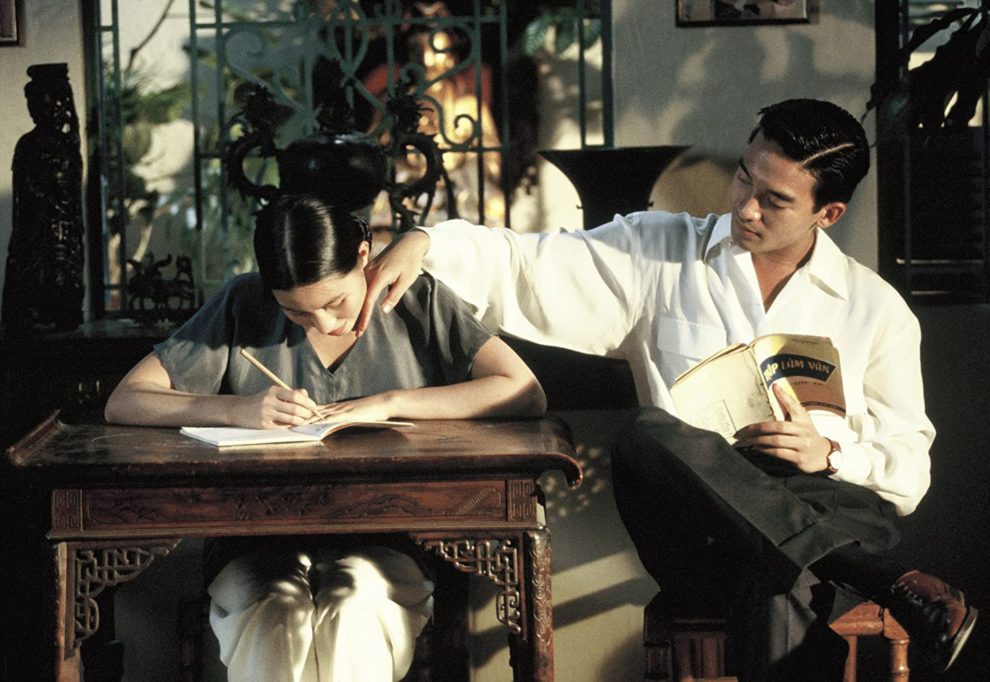

In the second section, ten years later, Mui is a young woman of twenty, who now works at a wealthy pianist's home, a friend of the older son at her earlier home and someone she has admired from young. This section, too, retains the curious flicker of the eyes in the older Mui (played by Tran Nu Yen Khe), who goes about her daily chores, with her innocence finding pleasure in serving fine dishes for the young pianist, or trying out his fiance's lipstick. Hardly any words are spoken here, and a gradual and palpable tension emerges between Mui and the handsome pianist.

Over the course of the two timelines, the film documents the life of Mui intersecting with the decline of a once-prosperous household plagued by the indiscretions of men and the suffering of women, and then gradually moving on to work in another place, occupying space with a man and his fiance.

“The Scent of Green Papaya” is remarkable, both as an aesthetic and political project, in exploring the everyday life of Vietnamese people, moving away from the largely Hollywood centred gaze toward Vietnam in the film media – of movies like “The Deer Hunter” (1978), “Apocalypse Now” (1979) or Oliver Stone's Vietnam Trilogy. The major plot event of the film can be said to be the 10-year cut: with several parallel stories, of death, of the decline of the first household running simultaneously, as the film's context is carefully created, as people live through shifting times. One of the major achievements of the film is that it never creates a saviour, or a good person who can emancipate the historically weaker sex. Tran is content to show the suffering, and though never overtly bleak, and instead brimming with a certain vigour, the film carefully reveals the footnotes to content life.

The film displays no sensationalism as seemingly provoked points of conflict that appear in the story pass with or without resolve as evidenced by Tran's elliptical editing. In the first section, the passage of time is more evident – also forming a major chunk of Mui's life whereas the second section, while temporally shorter, provides a glimpse into the ahead. The central theme is thus: life goes on. And in recreating this very ‘life', Tran is perhaps almost radical to tell the story of a woman, her position in terms of gender and class, in terms of even harmless pranks inflicted upon her by the young sons of the house as she goes about her work. In the second section too, Tran makes known to us the power relations vis-à-vis the pianist's feeling toward her and her position in that very transaction. Tran's camera is powerful, but never overbearing. There is hardly any attempt to be didactic, as perhaps empathy and nuance can be aroused only with an execution of distance from the action.

It would not be a stretch to call Tran Anh Hung a feminist in his approach towards domestic life, the life of washing dishes, of sharing bedtime conversations with fellow helpers, – also an attempt to retrace his Vietnamese roots (He left Vietnam for Paris when he was 12) in this film. Several nuances of the movie such as the wife's loneliness in the first household with an unfaithful husband and uncaring mother-in-law lay bare Tran's empathy towards his female characters.

Another aspect of the film that deserves much appreciation is the use of sound – in the diversity of the sounds of the natural world, as well as the soundtrack that subverts conventional scenario-driven use of non-diegetic sound, creating moments of tension in the banal. The sound occupies a parallel narrative, and it exists in pure harmony with the story and the visuals.

The movie also largely owes its critical acclaim to the tremendous performances by the actors – especially that of young Mui played by Lu Man San, wonderfully complemented by the older Mui played by Tran Nu Yen Khen, also the wife of the director and who has appeared in almost all of his films. Their eyes seem to be the same, and we see the traces of the older Mui in the younger one, and remnants of the younger Mui in the older. The lush visuals of the title have been photographed by Benoit Delhomme, known for his work on Tsai Ming-liang's “What Time is It There?” (2001), whose frames ooze with colour and texture.

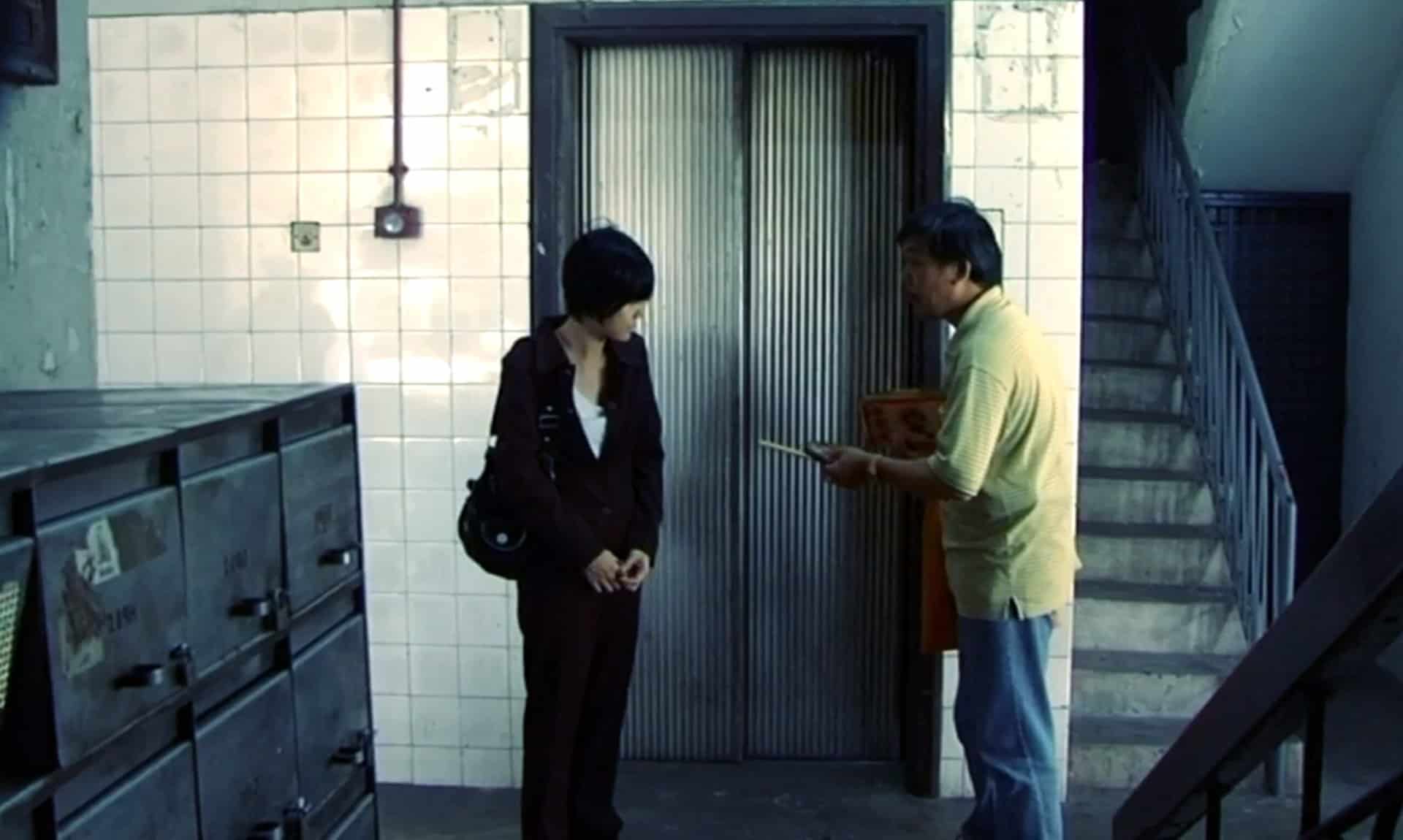

Tran's vision, as well as Delhomme's cinematography results in a stunning deconstruction of space, in elaborately set up mise-en-scenes, where the action even finds itself through the railings of staircases, and where multiple participants in a space, in their movement, inject a strange energy into the narrative in harmony with the space. The intimacy often calls to mind the films of Yasujiro Ozu in whose cinema too, imagined spaces are central to the narrative. The fluid tracking camera also works well to create an expanse of the space, never really revealing that the film itself was shot on a sound stage in a Paris suburb.

There have been a few critiques of the film in its insistent focus on aesthetic pleasures and form over the actual story and plot, as many of Tran's films have been called ‘difficult to understand'. However, in contrast to that, what is conveyed here is that Tran has managed to find a delicate balance amidst aesthetics and storytelling, both of which are interdependent and intersecting – and each wouldn't exist without the other. “The Scent of Green Papaya” appears as a clear precursor to Wong Kar-wai's In the “Mood for Love” (2000) where the images of dressing styles, the rain, the young pianist's hairstyle echoing Tony Leung's evoke a similar time period in similar sensation. Not to mention, a shot of the older Mui opening a window reminds one of Maggie Cheung looking out of a window in an early shot from Wong's film.

“The Scent of Green Papaya” stands as an important work of the 1990s, in the emergence of a new voice with distinct sensitivity and sensuality, and in the emergence of a country's cinema to the attention of the world.