Often compared to Buster Keaton and Jacques Tati, Palestinian director Elia Suleiman has developed during the years in both his short and feature films, a very original cinematic language, using rather few words and lots of sense of humour to observe and comment on the Israeli-Palestinian situation. The 2002 “Divine Intervention” is the film that fine tunes his trademark style, initiated in “Chronicle of a Disappearance” (1996) and that will evolve in “The Time That Remains” (2009) – a film based in part on his father's diaries – and in his latest “It Must Be Heaven” (2019) a work about, in the director's own words, the “Palestinisation of the Globe”. “Divine Intervention” is also the work that brought Suleiman under the international spotlight as it was nominated for the Palme d'Or award at the 2002 Cannes Film Festival and was also considered for the 2003 Academy Awards. Unfortunately, in a twist of fate that ironically resembles the director subtle sense of comedy, the submission was rejected as the Academy, at the time, did not consider Palestine a nation.

Divine Intervention is screening at ALFILM

The narrative of “Divine Intervention” – like in all his works – is hardly linear, but more episodic. The film is in fact a collection of vignettes that could possibly be stories heard from friends and neighbours or witnessed in first person by the filmmaker, and probably are, considering his habit of filling up many notebooks with his observations. The string of sketches presents characters and situations that comment on the absurdities of the everyday life in Israel and the West bank, in a dark, surreal humour, similar in part to the one that characterises Swedish director Roy Andersson's works.

The first third of the film is devoid of proper dialogues, almost silent, but a rich soundscape takes the lead in guiding through the sketches. In one memorable vignette, a man, every morning, methodically walks out of his home and throws his bag of litter in the neighbour's garden. One day, the neighbour's wife starts to throw all that rubbish back in the man's yard and he reacts asking why she is throwing garbage sacks in his yard. She replies: “this rubbish is the same rubbish that you threw to us”. “It doesn't matter” he answers, “it is still bad manners to throw it back”. In a rather poetic one, a laconic man waits for the bus and when reminded the bus is not coming, he states “I know”; behind him a wall graffiti reads “I am foolish because I love you”.

After this first section set in Nazareth, a recurrent story starts to delineate, focusing on E.S. (played by the director), a man living in Nazareth who has a girlfriend (Manal Khader) from Ramallah, and thus separated by several Israeli barriers. They only meet at Al-Ram checkpoint between Jerusalem and Ramallah, where they sit together in the car in a nearby parking lot and stare at the dumb soldiers assigned there, only caressing each other hands. Their meetings are the trigger for more gags and observations of the ridiculous and bully behaviour of soldiers and police officers, the climax being reached by the iconic episode of E.S. blowing a large red balloon bearing Yasser Arafat's smiley face and letting it fly passed the checkpoint, through the sky, scattering the bemused soldiers.

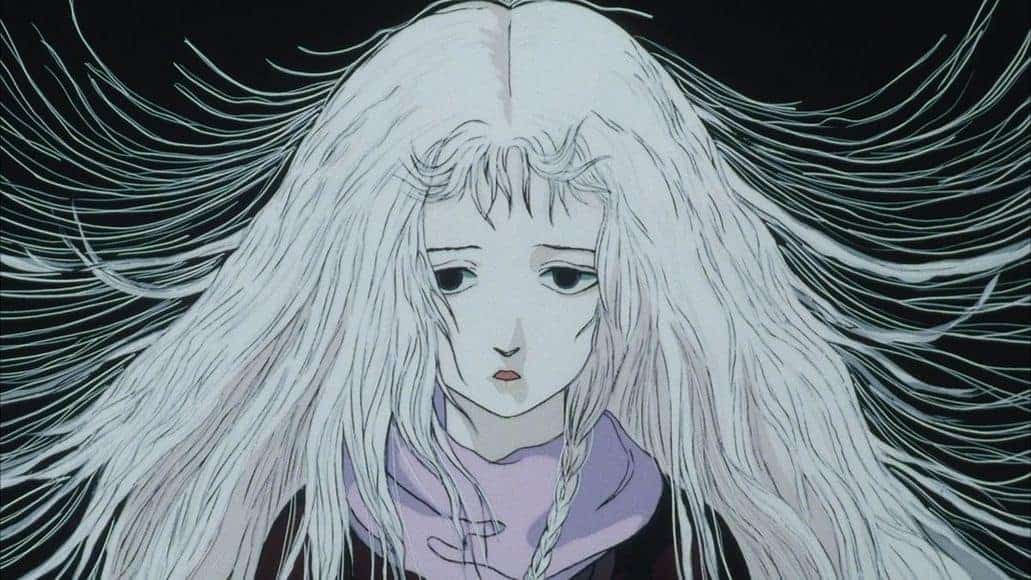

Suleiman's films have recurrent links to his family, his father especially (played by Nayef Fahoum Daher) and in “Divine Intervention” the director inserts a melancholic tribute in the form of sombre episodes about his illness and death. He will do the same for his mother in “The Time That Remains”. Another theme Suleiman certainly loves is the explosive energy that women can trigger. One of the best sketches sees Manal Khader in stilettoes, mini dress and charismatic dark sunglasses walking steadily and confidently towards the checkpoint, ignoring the soldiers' screams and pointed guns. As she passes the barrier under the soldiers confused eyes, the whole checkpoint lookout-tower noisily falls apart and crashes down. However, a final long episode where the woman turns into a flying ninja in a special-effect-rich sequence, is maybe the weakest of all. Simpler, brief silent scenes are the best, especially when played by Suleiman himself with his impassive expression. He eats an apricot while driving and throws the stone out of the window that hits a tank and makes it explode. Even more symbolically contextual, at the traffic light he stares at an Israeli driver in a car beside him and the man stares back at him; none of them wants to be the first to lower the challenging gaze and a long line of beeping cars forms behind the two stubborn drivers.

Suleiman is a master in catching the absurdity of everyday facts and present them dressed up in burlesque and poetry. His words “pleasure has the potential to threaten, to crack positions of authority” reminds me of an anarchist motto of the end of the 19th century that later became the slogan of the 1968 and 1977 student movements. “Fantasy will destroy power and a laughter will bury you!”