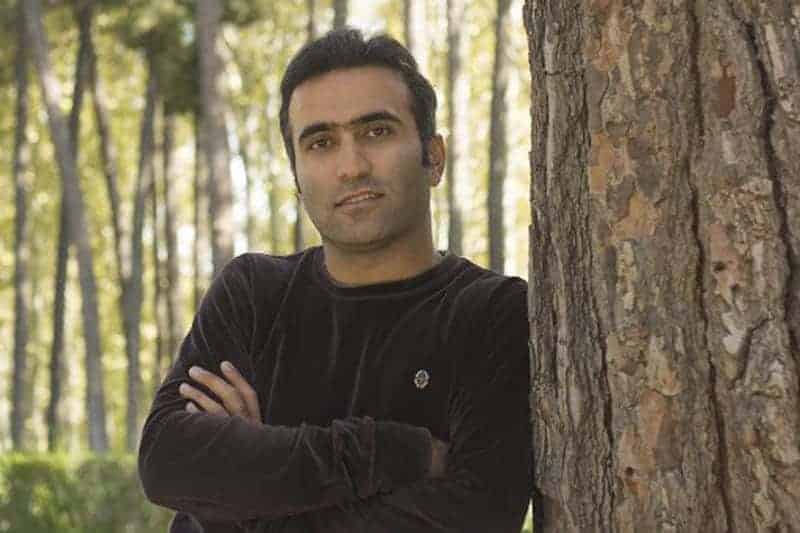

Born in Kobe, Japan, Oudai Kojima lived in New York City for 10 years before returning to Japan. After studying architecture at Tokyo University, he changed direction to filmmaking. He served as an assistant director to Tomokazu Yamada before going freelance and starting to direct full time. While directing numerous music videos, commercials and short films, he started work on his first feature film, Joint, in 2019. The film premiered at the 2021 Osaka Asian Film Festival and is scheduled for release in Japan in autumn 2021.

Kim Chang-bak is a S. Korean actor who was castein the film, but eventually also became part of the production, working as executive producer, in his first effort in the role.

On the occasion of “Joint” screening at New York Asian Film Festival, we speak with them about shooting a film about modern yakuza, crime, Korean immigrants, Shogen, Ikken Yamamoto and Kim Jin-cheol, the production in general, and the Japanese movie industry.

Why did you decide to shoot a film about modern Yakuza?

I had an interest in the genre of crime films. In Japan, there are not many modern yakuza or modern crime films in general and I thought it would be interesting to revisit the genre in modern times and try to present the category's tropes in a different, fresher fashion. I also thought it would be interesting to present protagonists that are not only full-fledged yakuza, but also low-level criminals.

Have you watched any of the classic Japanese yakuza films, like the ones by Kinji Fukasaku for example?

I did a few, but I did not really reference them in the movie. Instead, I tried to reference more American and European films, like the works of Michael Mann or Jacques Audiard.

Why, though? Why not reference Japanese filmmakers?

I did not want to have a Japanese mindset, I wanted to present the view of the outsider, because I lived in New York formerly and moved to Japan when I was 13, and I wanted to have that outside perspective, not shoot a film that follows the Japanese cinematic language; I wanted my movie to be fresh and off-beat.

How close to the current reality of yakuza are the events presented in the film?

15 years ago, the anti-Yakuza law was introduced, which prevents them from getting a job for five years after they declare their former status and officially resign, essentially preventing them from making a living. In my film, the yakuza are presented as not really powerful, but instead as people trying to survive as a criminal organization. That part is also realistic, as much as the ties with the lower and mid-level criminals, because in Tokyo, nowadays, the yakuza cannot embark into criminal activities themselves due to the rather strict police policies. Therefore, they have to use people who are not in the yakuza, the aforementioned, mid-level criminals, and also foreign ones.

What kind of research did you do for all these aspects?

For research, I watched a number of documentaries regarding current day Yakuza, and I did some interviews, not directly with Yakuza, but with individuals who know about the fraud “business” in general.

In the film, there is also an arc focusing on Korean immigrants. Can you tell me a bit more about this part?

For this part, I wanted to show that in Japan, there is more international crime activity; therefore, I presented not just the yakuza world, but a wider view of the crime world, whose components also include Chinese triads and Korean mafia. Also, there are others, who are not part of these groups but have criminal organizations of their own, frequently using illegal immigrants and I also wanted to incorporate that on the scale of the film.

The frequent use of handheld cameras and narration in the film induces it with a documentary-like sense. Why did you choose this approach?

Most Japanese yakuza films of the past are not very documentary-like, they have a visual style that looks more like a studio based production. I thought that using non-professional actors in a non-structured type of shooting would make the film more raw and intense, and essentially more realistic, as if the events depicted are happening “as we speak”. That is why I chose to use handheld cameras, but as the movie progressed, it becoma more structured as a shooting, because we used more tripods for example.

Can you give me some more info about the locations the film was shot?

We scouted with my cinematographer for quite a bit, about three months around Tokyo, and I tried to find locations that truly give a sense of criminal activity. For the Korean part, I looked for places actual immigrants live in. For the Yakuza part, I looked for places that could incorporate the Japanese style of housing, and for the IT tech businesses, I wanted this start-up company style to it. Shooting-wise, we had about 60% of the locations scouted beforehand, but for the rest, we had to scout as we shot. That part was really tough, but in the end, it turned out good.

I read that the film cost just around $50,000. Is that number accurate?

Yes, that was roughly the initial budget, and with advertising, it went a bit more

Could you give us some details about your involvement as an actor and producer in the movie, the overall production, and what was the hardest part in producing this film?

Kim Chang-bak: I started working in this film as an actor, but as soon as the production started, I got interested in that aspect also and I became involved in the pre-production and later, on the production itself.

Kojima: Regarding the production of the particular film, we started as a small project, with a couple of the main actors, including Ikken Yamamoto, the main lead, and the IT business guy, Ryo Sakuragi. There was a main group of people that really wanted to make a film together and I proposed an ensemble crime drama. We started to create a script, and more and more people got involved, and then we started auditioning. The basis of the production was that of an indie flick, but as more and more people got involved, including Kim Chang-bak, it became more of a structured production.

Kim Changbak: For me, the hardest part was trying to think of a way to make the film more approachable, how could an indie flick be shown to a wider audience, how could we make it appear more like a big, studio-based production. However, for the visual elements and the film itself, I was confident it had the quality. So the toughest part was securing investors and distribution.

How did you come to cast Shogen in the film?

Shogen is a friend of Ikken Yamamoto, since they played basketball together (Yamamoto was a former basketball player). Actually, a lot of members of the cast are Yamamoto's friends, including the big guy with the tattoo, who also plays basketball. We actually auditioned more than 400 people, but in the end, we had several characters that we did not have the perfect actors for, so we cast these roles with Yamamoto's friends. Because in reality, Yamamoto knew people who were more diverse and looked more original than the people who came to audition. Eventually, as we were thinking about the cast, Shogen came to mind, since we thought he would be perfect to portray a character whose nationality is vague and also had a high-class feel to him

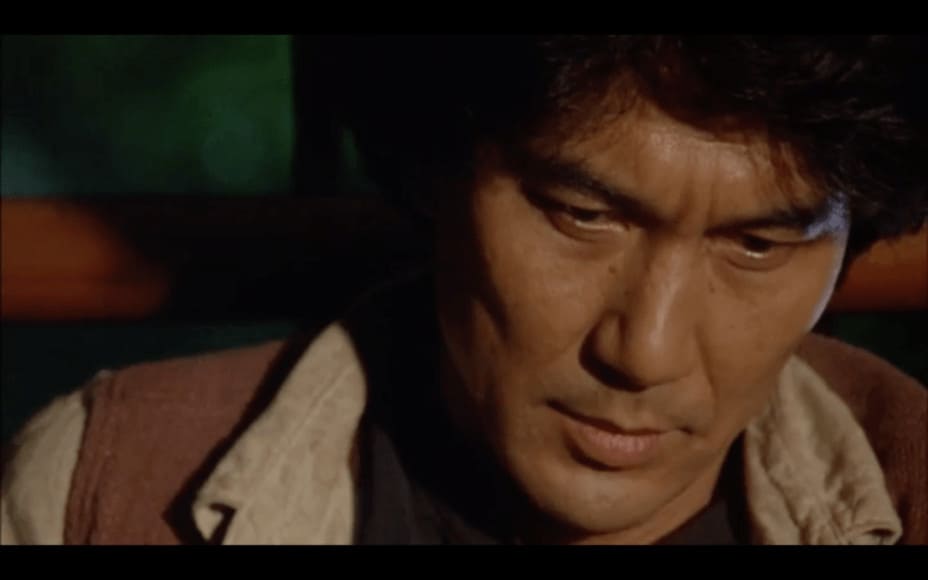

Can you give me some more details about your cooperation with Ikken Yamamoto and Kim Jin-cheol?

I graduated with a degree in architecture, but I decided to pursue filmmaking. However, in the beginning, I had real trouble creating films, but during the short ones I managed to shoot with Kim Jin-cheol, I realized that he was a great actor, and so I always wanted to cast him in one of my features; therefore, he was involved in the film from the beginning.

Yamamoto actually came to audition for one of my short films. He was really good, but he did not fit the role I had in mind at the time. However, I really wanted to collaborate with him in a feature film . During an after party of one of the short films, I met with Ryo Sakuragi and Kim Jin-cheol in a bar. By coincidence, Yamamoto also came to the same bar, and during that night, we talked about how we wanted to shoot a feature film, and he eventually agreed to come onboard as the lead actor.

“Joint” is not as violent as other yakuza films but there are still some moments of violence. Was it difficult shooting them?

I always thought these scenes would be rather difficult for a first-time filmmaker like me; to create realistic ones that is. I wanted to have violent scenes in the movie, but just a few of them, one in the middle and one in the end, one including a gun shot and one a fight, and make them as realistic as possible. I did not want these scenes to include guns, because in Japan it is almost impossible to create a realistic gun-shooting scene, because it is illegal and there are no blanks, like in Hollywood. Regarding the production, it was really difficult, but in general, we had an ad-lib shooting style, but as we were rehearsing, it became clearer what kind of shots we had to do, and what kind of tropes we had to use. In the end, it was harder to plan it than to realize it, in order to fit it in the film in a realistic and visceral way.

What is your opinion about the Japanese movie industry at the moment?

Kim Chang-bak: Before I came to Japan, I was an actor in S.Korea and regarding the production style and vibe in general, there are many differences between the two countries. However, since this is my first production in Japan, I do not have that much experience regarding the film industry. As a general idea, I feel it is really hard for Japanese filmmakers to make a realistic film that incorporates crime.

Oudai Kojima: It is really easy to implement a cheap, non-realistic style of filmmaking, because, first, the budget is really low in general, compared to Hollywood and Korea. However, it is really hard to shoot in Japan, location-wise and cast-wise for example, so the general environment for filmmakers is rather difficult, compared to other countries.

Has the film opened in Japanese cinemas?

It will start screening in November in Tokyo and then all around Japan.

Regarding the festivals it screened, how was the audience's reception?

In the first screening in Osaka, many people loved the film, particularly its realism. They often said that it felt different from Japanese films, regarding the cinematography for example.

Are you working on any new projects?

I am working on the screenplays of two projects. I am still researching, but I hope I will be able to shoot in a couple of years.