Dealing with themes of sexual/domestic abuse in mainstream (Japanese) cinema is not exactly the easiest thing to do. Yukihiko Tsutsumi, however, who shot “12 Suicidal Teens” back in 2019, seems like the man to do the job, in adapting Rio Shimamoto's Naoki Prize novel. Let us see how he fared.

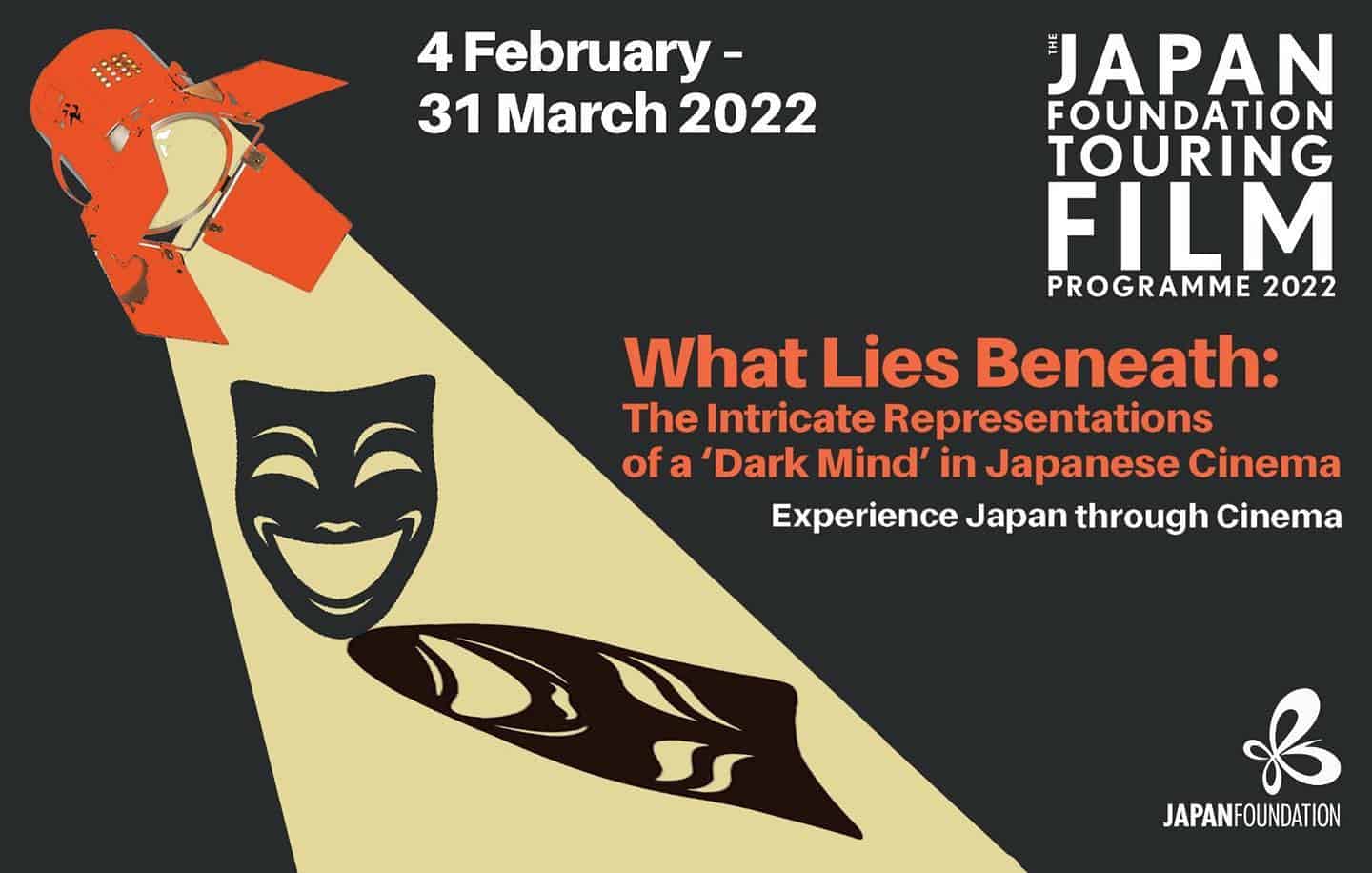

“First Love” is screening as part of the Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme

The protagonist of the story is Yuki Makabe, a psychologist who believes that the main blame for the violent behaviour of any children lies with their parents. Yuki lives a nice enough life, being respected in her field and married to photographer Gamon, who is set on taking care of her, essentially being in charge of all house chores due to his wife's rather busy schedule. At one point, Yuki becomes fascinated by the case of Kanna Hijiriyama, a college student who has been arrested for the fatal stabbing of her art professor father, with the crime becoming “front page” across the media. However, she soon discovers that the girl's lawyer is Kasho Anno, her husband's brother, with the strain among the psychologist and the lawyer being palpable from the beginning. Eventually, and as Kanna reveals various events of her past that have shaped her as an individual, Yuki decides to meet with the people involved, in a trip that also brings her face to face with her own past.

Yukihiko Tsutsumi directs a multilayered movie which comments on a number social, psychological and even philosophical issues, all of which eventually intermingle, to a degree at least. In that regard, the past of Kanna, which is eventually revealed as one of abuse from grown ups on a number of levels, is paralleled with that of Yuki's, who also suffered something similar, although in a radically different way, more indirectly that what happened to the girl. In that regard, Tsutsumi seems to want to focus on the strain the case puts on Yuki, as her client's trauma brings out her own, while the presence of Kasho, adds even more to the pressure.

Through these two stories, the director makes a comment on how the actions of parents can shape the life of their children, although in the cases of the two female protagonists, the path they ended up taking was radically different. This last aspect states that although the past can shape the future, even indirectly, it does not mean that is the most crucial factor on how the life of any individual progresses, since Yuki, despite her trauma, has truly managed to overcome. On the other hand, the accusation towards parents is quite pointed here, both towards the fathers as perpetrators, but also towards the mothers, for their attitude that lacked any kind of protection towards their children. Kanna's mother in particular, highlights this aspect in the best fashion through her infuriating attitude, in a number of the most memorable scenes in the movie, courtesy of the excellent performance of Yoshino Kimura in the part.

On the other hand, and despite the rather rich context, the narrative as a whole has a number of issues. The first one is that, despite the way it highlights Yuki's past and intensifies her current strain, her story with her brother-in-law is quite disconnected, while her husband's overall attitude can easily be described as ‘too good to be true'. The same applies to the whole concept of photography, which is though, a secondary one, but even worse, to the court drama axis, which is rather lacklustre, also due to a rather significant, overall fault of the direction, which strips almost all the twists of the story of the impact they could have, despite the fact that their essence is quite shocking. Furthermore, and in conjunction with the music, Tsutsumi hits the reef of forced sentimentalism on a number of scenes, which look unnecessary melodramatic.

The aforementioned approach also hurts the acting, with Keiko Kitagawa as Yuki suffering particularly on the whole approach to the story, with the same applying, although on a secondary level, to Tomoya Nakamura as Kasho and Yosuke Kubozuka as Gamon. However, the protagonists exhibit a sense of measure that definitely benefits the film, with the same applying to another secondary character, played by Hoshi Ishida. Kyoko Yoshine on the other hand, is hyperbolic on occasion, in probably the weakest performance in the movie.

The production values, on the other hand, are on a very high level. The cinematography captures the bleakness of the narrative through both framing and coloring, while the editing allows for the various flashbacks to be well placed, also inducing the movie with a very fitting, relatively fast pace.

“First Love” is not a bad film, as the story and the overall comments are both intriguing and interesting. In the end, though, as a whole, it is more easily to be described as a missed opportunity for something great, than a properly good movie.