by Earl Jackson

In Part 1 I sketched a brief cinema-historical survey of Chekov in Japanese cinema, as a background for a more direct appreciation of “Drive My Car” here in Part 2. Staying with the focus on theater, I will consider three aspects of the film's structure and internal dynamics: the orchestration of voices, “Uncle Vanya”, and Noh. Ryusuke Hamaguchi seems to inhabit a universe similar to that of Patricia Highsmith – one composed of seemingly random details whose significance depends on the kind of attention paid to them. When Yusuke asks the dramaturg Gong Yoon-soo (Jin Dae-yeon) why he had learned Japanese, Yoon-soo replied that as a graduate student he had studied Noh at Waseda University for two years. This would also explain why he was so interested in the experimental version of “Uncle Vanya” they were rehearsing (on the level of plot) and would provide a key to the radical independence of voices from their speaker (on the level of representation).

The interface between plot and structure I'm suggesting here will become clearer with one more detour: a reading of the climactic scene from an earlier film, “The Ceiling at Utsunomiya” [怪異宇都宮釣天井] (Nobuo Nakagawa, 1956). Although the two films discussed in Part One shared references to Chekov, Nakagawa's film actually is closer to “Drive My Car” in structural innovation, in that it also presents the dialogue of an earlier theater piece simultaneously as it had been performed and in contexts that give it another level of meanings altogether.

“The Ceiling at Utsunomiya” is a hybrid genre- both jidaigeki and thriller. Set in the fiefdom of Utsunomiya, it focuses on a complex assassination plot against the Shogun Iemitsu (Yōichi Numata). In preparing for the shogun's visit, the daimyo has commissioned an army of carpenters, engineers, and stone cutters to create a mechanically-powered suspended ceiling in a large banquet room, in which the shogun and his entourage will be entertained. After dining, the shogun will be invited to remain in the room for a folk-dance performance, during which time the ceiling will be lowered and the suspending bonds released, sending both the ceiling and tons of rock down on both intended and collateral victims.

The Shogun's spies, however, discover the plot and are able to head the Shogun off, urging him to pass by Utsunomiya to safety in Nikko, but the Shogun insists on visiting as planned. Once in the deadly hall, when his hosts are about to retreat, the shogun announces that instead of watching a performance, he will perform himself and orders his hosts to remain as he, along with his chorus, perform the kusemai – a conventional dance in the finale of the warrior Noh play, “Kiyotsune”. The hosts have no choice, and the tension they feel is underscored by the crosscutting between the Shogun's performance and the mechanism above the ceiling, where one of the carpenters is forced at swordpoint to set the deadly descent into motion.

Like most of the warrior Noh plays, this one deals with a member of the Heike, the losing side of Genpei civil war between the Taira and Minamoto clans. But Taira Kiyotsune is an unusual figure, because he did not die in battle, but committed suicide by throwing himself in the ocean. In the first half of the play, Kiyotsune's wife confronts his ghost with her anger at his death. He apologizes to her and explains his decision to die, and describes the Ashura hell he had fallen in before attaining Buddhahood. Ashura is a hell of perpetual fighting for warriors who died in battle (so technically Kiyotsune should not have been there). In that hell, the ghost sees every ordinary aspect of the natural world as a threatening enemy. In his testimony to his wife, Kiyotsune sees double: both the natural world and how the delusion transformed it. In performing the kusemai, the Shogun doubles the double vision while placing the truth elsewhere. When Kiyotsune sees the world as enemy soldiers, it is a delusion; when the Shogun performs “Kiyotsune” -he sees the beautiful hall as a deadly weapon and his hosts as his would-be killers – and that is completely accurate.

The language of Noh is highly allusive, using pivot words (kakekotoba) and puns based on homonyms. While the Chinese characters may fix the meaning on the page, the recitation destabilizes the meanings into multiple interpretations. In the table below I excerpt some of the lines from the kusemai, and provide both literal level and secondary level meanings. The final line, I argue, has an added meaning specifically in the performance within the film that it would not have in the original Noh.

| Lines from “Kiyotsune” | Translation |

| さて修羅道におちこちの…Sate shuradō ni ochikochi no | “I have fallen into the Asura Hell” *Ochikochi – is both “have fallen” and “here and there” [connects with next line] (Fig.1) |

| 立つ木は敵Tazuki wa kataki 雨は矢先。ame wa yasaki | The standing trees are enemies And the raindrops are tips of arrows |

| 月は清剣 Tsuki wa seiken 山は鉄城。yama wa tetsujō | The moon is a gleaming sword The mountain an iron castle |

| 雲の旗手をついてKumo no hatate o tsuite | Meaning 1: Arriving at the far ends of the clouds. Meaning 2: The clouds are battle flags A dagger pierces |

| げにも心は清経がGeni ni mo kokoro wa kiyotsune ga | Meaning 1. In truth the heart is purified [kiyo] Meaning 2. In truth the heart, Kiyotsune |

| 仏果を得しこそ有難けれBukka o eshi koso arigatakere. | Meaning 1. has attained Buddha hood [and am grateful] Meaning 2 [in film only] : I have found the weapon!* |

Fig. 1. “I have fallen into Ashura Hell.”

The scene is structured, controlled and maintained within the kusemai of Kiyotsune. A kusemai is a fixed structure and its movements are the same across all plays, therefore both the length of time the Shogun takes and the gestures are recognized parts of the dance grammar (Fig 2).

Fig.2 “The standing trees here and there are enemies. The raindrops tips of arrows”

The tension here is enhanced by a knowledge of the play and specifically by a knowledge of the conventions of the dance itself. Furthermore, the points at which the dancer will brandish the sword, and where and when he will point it are also fixed, thus the gestures of the Shogun are at once deliberate and literally pointing at his real enemies and simply dictated by the pattern of the kusemai (Fig. 3). This doubled meaning is in turn doubled by intercutting with what is happening above the ceiling: the shogun pointing his sword at the daimyo is intercut with the conspirator's sword threatening the hapless carpenter at the winch (Fig.4).

Fig. 3. Pointing the sword at the conspirator.

Fig. 4. The henchmen pointing the sword at the carpenter.

Immediately after the final note in the kusemai is sounded, the ceiling begins to collapse. The Shogun dodges the stones and captures his devious hosts (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. “Kiyotsune has attained Buddhahood”/ “I have found the weapon.”

Of course, as a performance tradition, Noh would be difficult to compare with the European realist theater that Chekov exemplifies. In the Noh play, Kiyotsune only sings two of the lines in the kusemai – the rest is sung by the chorus, alternating fluidly between first-person and third-person. On Chekov's stage, each actor becomes the character they portray, and each character represents a single, psychologically coherent individual. On a Noh stage, a persona is evoked. Whether it be Kiyotsune, Ariwara no Narihira, of Yamaba, the persona is generated by the total configuration of main performer (the shite), the chorus, the music, etc.. The mode of being of that persona is closer to music than to an individual – evoked to dissipate at the conclusion, recalling Jean-Paul Sartre's question in “L'Imaginaire” about the “existence” and location of Beethoven's “Seventh Symphony” – that it is neither in the score nor a specific instrument in the orchestra but only temporarily present (as an event) during the performance.

In terms of “Drive my Car”, however, this absolute difference between Noh and western drama only holds for the performance of “Uncle Vanya”. The film devotes far more time to the preparation for the performance, and in that, the similarities are suggestive. In the Noh, “Kiyotsune” is a product of the voices that circulate. And in “Drive my Car,” the voices also circulate – among the actors in rehearsal and most significantly, in his wife Oto's (Reika Kirishima) voice taking all parts but Vanya on the tapes Yusuke listens to and responds to. The excerpts from the play out of context become commentary in the new context of Yusuke's life and silences. Both Nakagawa's and Hamaguchi's films hinge on a “plot device” that each film first literalizes and then transforms it into a vehicle for an additional level of meaning: both the rigged ceiling and the cassette tape are machines, but their uses involve the creation of a second narrative level in Nakagawa's film and a versatile technology of subjectivity in Hamaguchi's.

On the way to Narita airport, Yusuke begins as Vanya: “No one understands how I am feeling. My anger and frustration make sleep impossible. I wasted so much of my life. I could have attained so much more. Now at this age, it's no use.” His complaints are met with disapproval from both Sonia and Vanya's mother, in Oto's voice. Yusuke's utterance is also contradictory in that he is convincing because he is an accomplished actor so his delivery itself is evidence of the achievements his words deny. On the other hand, the powerful delivery of the lines remains as affect independent of who spoke them or why: the lines convey a real feeling untethered to an identifiable speaker. As the film progresses, however, situations contextualize unintended meanings of Chekov's dialogue delivered both by Yusuke and by Oto's disembodied voice.

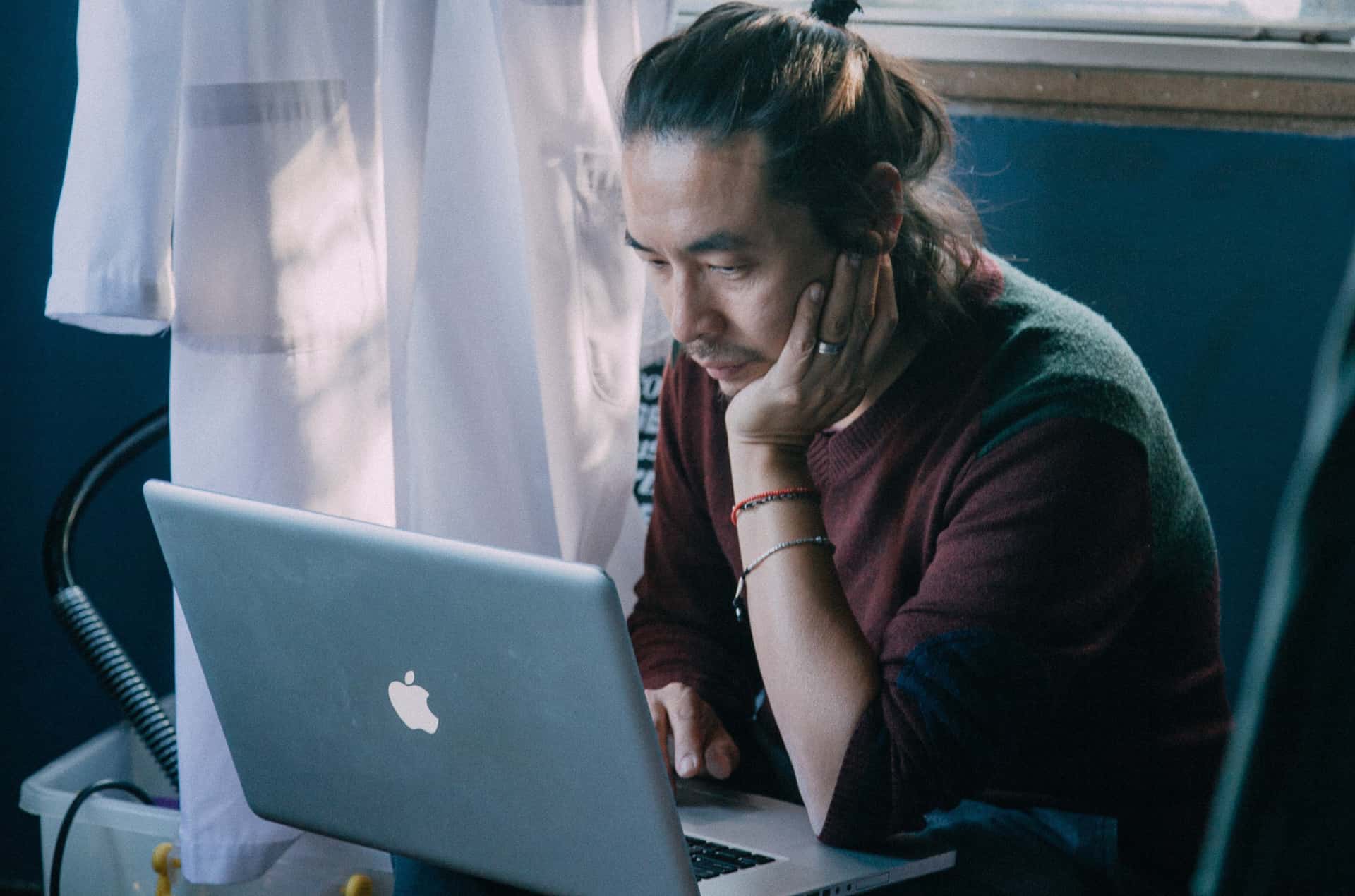

The first such transformation of dialogue comes from Yusuke's recent history, rather than his past. An early scene recalls “All About Eve”, when Yusuke is in his dressing room after a performance of “Waiting for Godot”, when Oto brings in a young actor, Takatsuki Kōji (Masami Okada ) who gushes like Eve Harrington, and later proves to be just as monstrous, albeit in different ways. While Harrington's ambition preempted a conscience and the capacity for empathy, Takatsuki's filled his emptiness with appetites he fails to control (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Oto introduces admiring actor Kōji Takatsuki to Yusuke.

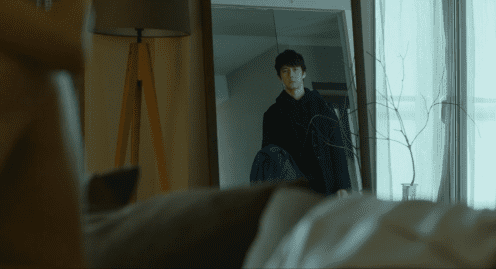

Returning unexpectedly from Narita airport the day his flight to Russia was postponed, Yusuke walks into his apartment to find his wife and Takatsuki having sex. The trauma is figured as a disassociation: the shot shows not Yusuke, but his reflection watching (Fig. 7) He leaves unseen and returns to the airport and never tells his wife that he had been there.

Fig.7. The reflection looks on in the mirror's silence.

What he sees provides a new context for his dialogue with the Uncle Vanya tape on the way home a week later.

Yusuke: For 25 years he has been pretending to be someone that he isn't. Strutting around like a prince.

Oto's voice [as Dr. Astrov]: You seem envious of him.

Yusuke: I'm very envious. His record with women. I doubt Don Juan himself would have had more action.

While Yusuke's utterance in the previous excerpt is affectively powerful, the imposition of context in the second is important in terms of Hamaguchi's ethics. Hamaguchi's previous work evinces not only a belief in the voice but in the absolute importance of recognizing who is speaking. This is most powerful and poignant in the Tohoku Tsunami documentary trilogy he codirected with Ko Sakai: “The Sound of Waves” (2012); “Voices from the Waves” (2013) and “Storytellers” (2013). In this trilogy, Hamaguchi and Sakai move from the conventional interview format to pairing survivors to talk to each other about their shared and divergent experiences – those dialogues constitute a unique testimony, as does the third film in which people from Miyagi prefecture tell folk tales in the rich and complexly rough-hewn Miyagi dialect. Of course, the fictional Yusuke's personal dilemma does not reach the level of tragedy or dignity of the real-life survivors of the catastrophe in Tohoku. Instead, Yusuke's situation allows the dual meanings of Chekov's dialogue a clarity both on stage and in the car.

Who speaks is painfully significant in the next excerpt as it begins with Oto's voice as Dr. Astrov asking, “Is she faithful to him?” Yūsuke's answer is Vanya's answer, but the meanings of the terms are completely reversed:

Yūsuke: Yes, unfortunately

Oto's voice [as Astrov]: Why do you say unfortunately?

Yūsuke: Because that woman's faithfulness is false from beginning to end.

Rich in rhetoric but devoid of logic. (Fig. 8)

Fig. 8. “Was she faithful to him?” “Yes, unfortunately.”

From a superficial view, if the question of faithfulness refers to Oto, the answer would be “no”. But Yūsuke is convinced of Oto's love and her commitment to their togetherness. “Faithlessness” is inapplicable, which, on the other hand, keeps Yūsuke from either confronting Oto or fully acknowledging his feelings of betrayal, not to mention his fear that speaking with her about it would endanger their full togetherness that has not been threatened by her extramarital sexual experiences. Just as Vanya changes the value of “faithfulness”, Yūsuke redefines and rejects “unfaithfulness”.

Yūsuke drives around for hours to avoid the conversation that Oto asked to have, fearing that he may have to hear her speak of “unfaithfulness”. The dialogues he practices as he finally approaches the apartment and parks are especially fraught.

Yūsuke: My life is lost and gone without any way of retrieving it.

This idea plagues me night and day like a devil. . . . What should I do a bout my life and my love? (Fig. 9)

Oto [as Helena]: When you speak to me of your love, I grow numb and don't know how to answer you.

Fig. 9. “What should I do about my life and love?”

Once Yusuke has parked, he practices Vanya's final despair and hear Sonia's long consolation in Oto's voice, not knowing that he is about to lose Oto forever when he enters the apartment.

Yusuke: I'm suffering. I wish you knew how much I suffer.

Oto's voice [as Sonia]: It can't be helped. There is nothing for it but to live our lives. . . We will live through the long, long days and endless nights. With patience we will live through the trials in store for us [Yusuke puts in eye drops] . . .When our time has come, we will pass away quietly [the eye drops run down his cheek like a tear]. (Fig. 10)

Yusuke listens to the final speech in its entirety. The eye drops giving the appearance of crying underscores the simultaneous event of acting a fictional role and suffering in real life, made more ironic as he is about to discover the woman whose voice is prompting him [Oto] and pretending to comfort him [as Sonia] is dead.

Fig. 10. “We suffered. . . . We cried.”

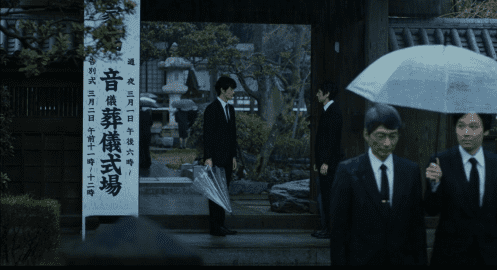

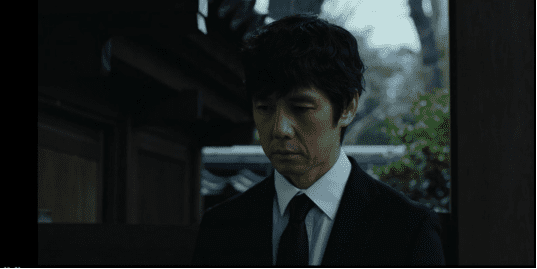

The next significant form of the circulation of the voice comes in a sound bridge at the end of Oto's funeral. Yusuke maintains his composure when he sees Takatsuki at the funeral, but when he silently returns his bow after it is over, he seems to condemn himself in the voiceover with a line that previously seemed to refer to Takatsuki: “For 25 years he has pretended to be someone he is not”. This now seems to refer both to Yusuke's profession as an actor and his refusal to discuss Oto's sexual infidelities.

Fig. 11. Facing Takatsuki at the funeral.

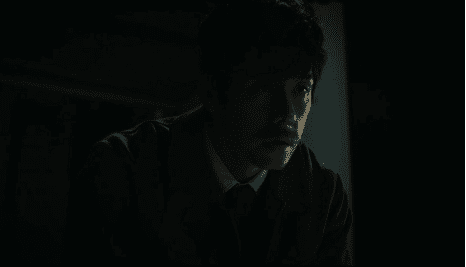

Fig. 12. “For 25 years he has pretended to be someone he is not”.

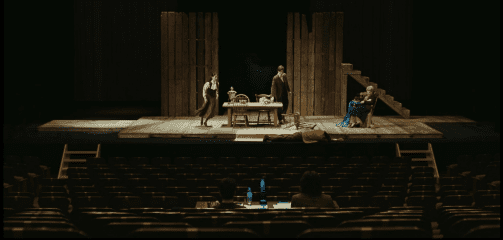

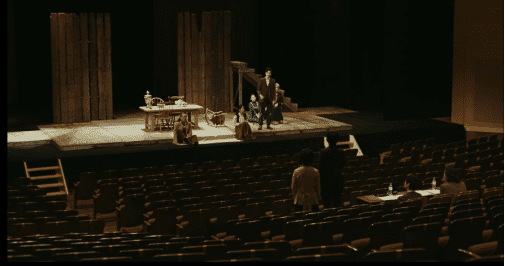

This line, however, is a sound bridge to the next scene with Yusuke on stage as Uncle Vanya in a full production of the play (Fig. 13). Now the voices have been located in 3-dimensional bodies and the individual forms of suffering and lament are restored to their original characters.

Fig. 13. The voices restored to the characters.

The play, however, continues to complicate the relation between Yusuke and his role. In this performance he omits lines he had already rehearsed in the car with the tape, and he breaks down and walks back stage to recover (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14. Suffering Backstage.

The other complication arises on the level of the film's presentation, which considers not only the relation of Yusuke to Vanya, but the relation of Hidetoshi Nishijima to both. In “The Ceiling at Utsunomiya”, the Shogun speaks to his would-be killers through the words of the ghost of Kiyotsune (both in lines he sings himself and those of the chorus) and thus remains the Shogun and the conduit for the Kiyotsune persona. But the actor Yōichi Numata was a western-style film actor and not trained in Noh- he only learned the dance for the role, and imitated a Noh actor. Similarly, Shotaro Hanayanagi (1894-1965) was basically a Shinpa (New School) theater actor who nevertheless played a Kabuki actor in “Story of the Last Chrysanthemum” [残菊物語] (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1939) and a Noh actor in “The Song Lantern” 歌行灯 (Mikio Naruse 1943). In both cases, the performance constitutes a gifted western-style actor approximating an art form not his own. Although Ichikawa Raizo (1931-1969) had been adopted into a Kabuki family and trained and performed in Kabuki, he left the theater for a distinguished career as a film actor. His Kabuki training could not elevate Ichikawa's attempt to perform as a Noh actor in Teinosuke Kinugasa's 1960 remake of “The Song Lantern” to anything beyond an imitation. Nishijima, however, is the same kind of actor as Yusuke, and equally dedicated and serious about his art. When Yusuke performs “Uncle Vanya” in the car, on stage, or in rehearsals, however, Nishijima is also engaging in the acting tradition he has worked in for years. These sequences therefore, constitute a complex configuration of performance and process, artifice and actuality. The rehearsals with Nishijima as Yusuke directing, and the stage production with Yusuke both acting and directing, also resonate with the original production of “Uncle Vanya” in 1898, which was directed by the legendary Konstantin Stanislavski, who also took the role of Dr. Androv.

The rehearsals and eventual staging of “Uncle Vanya” are set apart, not merely with the on-screen designation: “Two Years Later” but with the opening credits beginning to run as Yusuke is driving to Hiroshima. When the opening credits interrupted “Blissfully Yours” (Apichatpong Weerasethakul 2002) a third of the way into the film's running time, it served partially as an alienation effect and partially as an analogy to the crossing of boundaries- between the city and the forest and the Thai-Myanmar border. In “Drive My Car” the credits not only retroactively suggest that the previous 40 minutes were a preface, but that both the new rehearsal space and the historical significance of Hiroshima constitute, demand a heightened level of commitment from both the onscreen figures and the spectator.

The rehearsals offer intense exercises in an actor's relation to the text. Yusuke's insistence in the early stages that the actor should not perform but simply read the text recalls the regime Robert Bresson imposed on his “models” to allow an ineffable quality to radiate from the individual, uncompromised by theatrics. Each actor's speaking in their own language would also encourage essential differences to emerge.

Although it seems unlikely that Hamaguchi intended to infuse the stage with political allegories, the history of Japan in Asia makes such allegories a ready option. It is hard to overlook the fact that two of the actors who are foregrounded are from former Japanese colonies: Janice Chang (Sonia Yuan/Yuan Ziyun) from Taiwan and Park Yu-rim (Lee Yoo-na) from Korea. Nevertheless, Takatsuki's sexual predation of Janice primarily serves as an exposition of his character and not a historical metaphor. Realizing that Yusuke had seen Janice in Takatsuki's car the morning both were late, Takatsuki hopes to smooth things over, but as so often in with Hamaguchi's characters, Takatsuki's attempt to present a better self-image only exposed his baser nature. In fact, the dialogue ends in a logical contradiction.

Takatsuki: I am sorry about this morning.

Yusuke: It's ok.

Takatsuki: I was only advising her on her concerns.

Yusuke: You say that, but you can't speak English or Chinese. And she can't understand Japanese.

Takatsuki: Yes. And for that reason, of course, after all . . .

There is no English translation that can capture the placid cynicism and complete abdication of personal responsibility in Takatsuki's last line: なので、結局… Once again, Takatsuki revealed who he is – a kind of pathological variation on the processes of discovery the actors engage in the rehearsals. It is no accident that he masters the role of Vanya at the same time he finally must face the consequences of his darker impulses (Figs. 15-17).

Fig. 15. Takatsuki as Vanya attempts murder.

Fig. 16. Takatsuki drained by his performance.

Fig. 17. Takatsuki charged with, and admits to murder.

Lee Yoo-na is a different story altogether, and neither her Korean nationality nor history can be set aside in this case. A dancer whose career was cut short by a personal tragedy, Yoo-na decided to try acting, delivering her lines through Korean Sign Language, because she is mute.

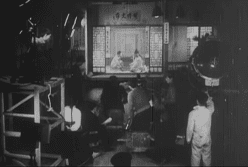

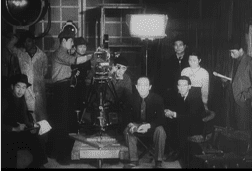

Under colonial rule, Japanese language became the official language of teaching in Korean classrooms, and students caught speaking Korean were subjected to punishment. The history of Korean cinema also evinces a silencing relevant to the power of Yoo-na's performance. For example, “Spring on the Korean Peninsula” [반도의 봄] (Lee Byong-il 1941) opens with a Korean language restaging of the beloved folk story of Chunghyang. It continues until someone yells, “Cut” when the scene reveals a film studio. The entire production team speaks in Japanese, and the actors off set also speak Japanese in other social situations throughout the film (Fig. 18).

Fig. 18a Chunhyang in Korean

Fig. 18b. Japanese-speaking production team.

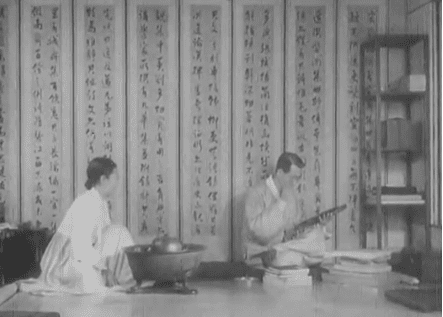

“The Straits of Joseon” [조선해협] (Park Gi-chae 1943) features an elderly Korean couple in mourning for their eldest son who died fighting as a Japanese soldier and preparing to send the second son off to war. Although the father is clearly a traditional Korean intellectual, he, his wife, and two surviving adult children speak exclusively in Japanese (Fig. 19).

Fig. 19. Why are they speaking Japanese? Straits of Joseon (1943)

In adopting “practical” work-arounds for non-Korean actors, even contemporary Korean cinema evinces a post-colonial imbalance. When the Taiwanese superstar Chang Chen appeared in “Breath” [숨] ( Kim Ki-duk 2007), the script had his character cut his own throat before his first scene, rending him silent for the entire film (Fig. 20).

Fig. 20. Chang Chen, throat bandaged and silenced. “Breath”. 2008

On the other hand, in “Dream” [미몽] (Kim Ki-duk 2008), Joe Odagiri, playing Jin, a carver of stamps in Seoul, speaks Japanese to everyone who simply understands him, including Ran (Lee Na-young), a young Korean woman who is in danger of being killed by Jin's dreams (Fig. 21) (Ironically, the Korean title is “Sweet Dream”, the title of a Colonial era Japanese melodrama whose alternative title is “Lullaby of Death” [미몽 죽음의자장가] [Yang Ju-nam 1936].)

Fig. 21. Lee Na-young, forced to understand Odagiri Joe's Japanese and live out his dreams. “Dream”. 2008.

From this perspective, it is already refreshing to hear Janice Chang speak Mandarin and Ryu Jeong-eui (Ahn Hwi-tae) speak Korean in the Vanya rehearsals and on stage. But Yoo-na's achievement is even more powerful: a silenced Korean woman who speaks through her silence with an eloquence that literally surrounds the director and title character of the production. Yoo-na integrated her prowess as a dancer with the compelling gestural vivacity of her language – a language both ideographic and haptic, tactile and tremulous.

Yusuke first listened to Sonia's monologue in Ota's voice, in the garage before he discovered her death. On screen, the car sat in a cement tomb-like cell, from which the disembodied voice gave her mournful attempt to console in describing life-long suffering and rest only in the afterlife. Now, on stage, a healing Yusuke has assumed the role of Vanya, and allows the new, embodied Sonia to enmesh him in her monologue – a language itself that is corporeal and capable of touch. Oto's voice from the machine was a prompt to repeat a line. Sonia's language can point (Fig. 22), can illustrate (Fig. 23), and can embrace (Fig 24). The production ends in that embrace accepting the darkness that enfolds everything but the lamp still burning. And the film ends with the open questions of survival and redemption across the mysteries of the self and its arts.

Fig. 22. “In that immense beyond, we will tell Him”

Fig. 23. “That life was hard”

Fig. 24 “We shall rest”

***********

Dedicated to the memory of Professor Karen Brazell (1938-2012), who taught me about Noh, and so much more.