Violence in cinema has always been a polarizing element, with film buffs frequently fighting about the dilemma of beauty versus violence, with the question essentially separating two of the larger groups of audiences, the art-house and the cult ones. The truth remains that violence has been used in different ways throughout the history of cinema, both to entertain in its simplest form (torture porn is one terms associated with this approach) and to present intricate comments by shocking. In this list, we have included movies that include both, while also highlighting that artfulness can also be found within violence, as much as mindless action. Considering that violence does not always equal action and with an effort to include as much diversity in its presentation as in the selection of the filmmakers included here (we failed miserably with Miike though), 40 of the most intense and violent Asian movies ever shot

1. Emperor Tomato Ketchup (Shuji Terayama, 1971, Japan)

Shuji Terayama, who was also a stage writer and a poet, is considered the leading representative of avant-garde in Japan. His works were always provocative and against all taboo, and “Emperor Tomato Ketchup” is a distinctive sample of the fact. Set in a Japan where children have gained control, the film depicts a variety of scenes, unprecedented in their extremity at the time, including children's nude and erotic scenes and offspring humiliating their parents. Being evidently low budget, the movie is shot in black and white and entails an abstract narrative, thus making it tough to watch, especially in its unedited form that lasts 75 minutes. However, underneath its extreme depictions and surrealism, Terayama hides a satire regarding politics and sex and the results of their interaction. Due to heavy censorship in Japan, the film was initially released as a 27 minute short, with the original cut eventually screened in 1993, 13 years after Terayama's death. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

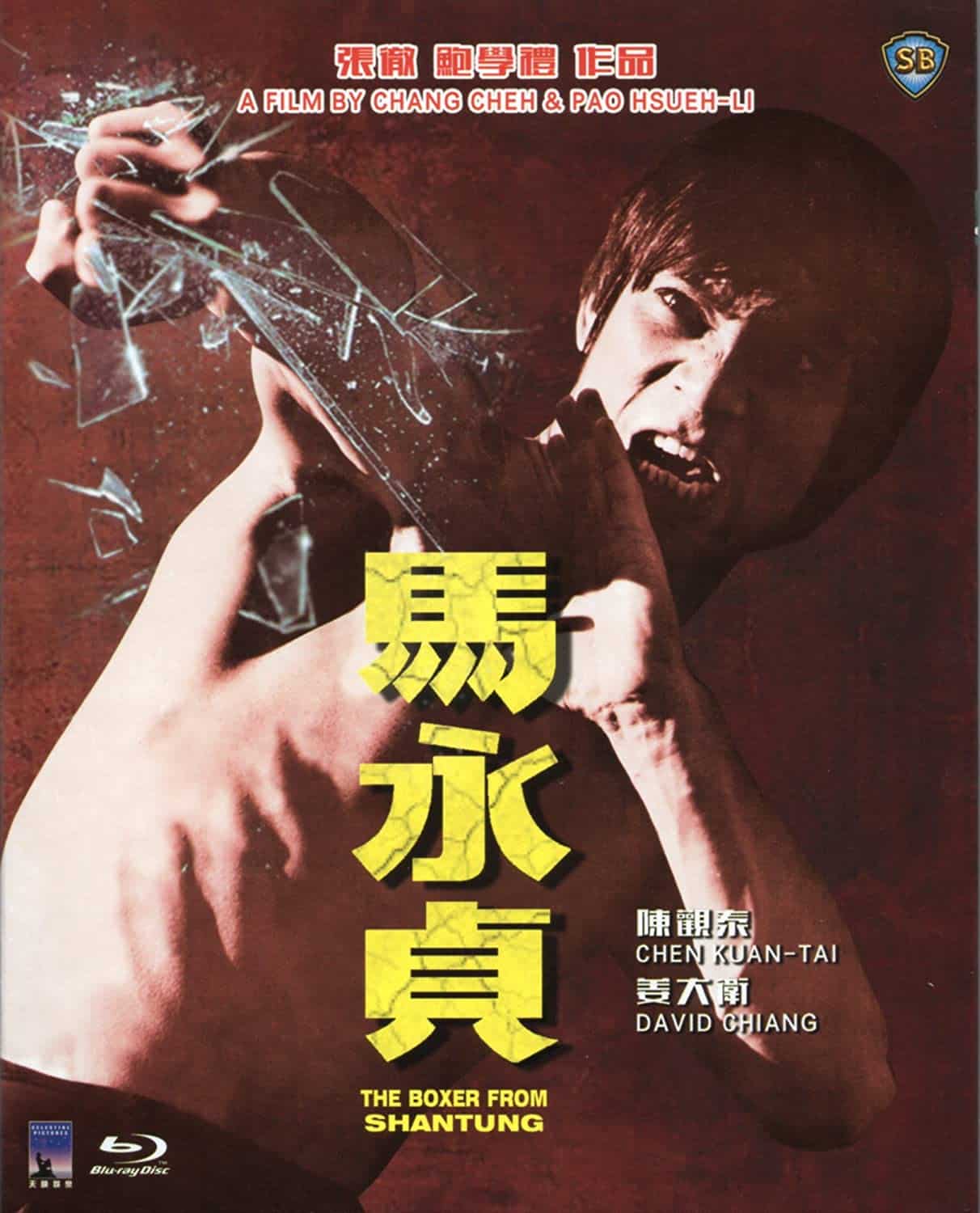

2. The Boxer From Shantung (Chang Cheh and Pao Hsueh-li, 1972, Hong Kong)

Chang Cheh was renowned for the blood spilt in his martial arts epics. Never more so than in this claret-drenched rise and fall story of gangster Ma Yung Chen. A breakout role for Chen Kuan-tai as the titular boxer seeking his fortune. This classic features a final reel of intense carnage that still manages to impress to this day. A perfect introduction to the world of Chang Cheh.

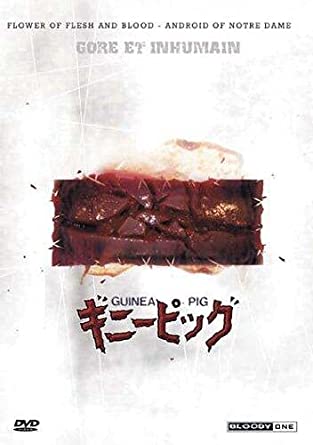

3. Guinea Pig 2: Flower of Flesh and Blood (Hideshi Hino, 1985, Japan)

This is the second and most vicious part of a series of seven splatter video movies, whose violent scenes were realistic to the point that the producers were forced to prove to the authorities that none of the actors were literally traumatized or murdered.

Hideshi Hino directs a collage of beating, torture and other sadistic exercises, instead of an actual movie. The particular segment gained notoriety for two reasons. First, Charlie Sheen, after watching the film, believed it was a snuff film and delivered it to the FBI to investigate it. Second, upon the research in serial killer Tsutomu Miyazaki's house, the police discovered a videotape of the movie that resulted in the public's belief that he was inspired by it. However, it was later disclosed that it was, in fact, the sixth segment of the series. Unavoidably, the Japanese authorities banned “Flower of Flesh and Blood” and no one could find a copy until its re-release by a German company in 2002, while a full edition was released in the US in 2005. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

Buy This Title

on Amazon by clicking on the image below

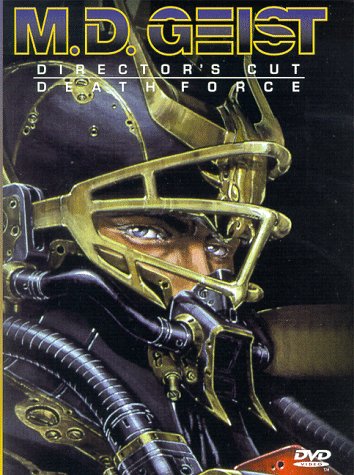

4. M.D. Geist (Hayato Ikeda, 1986, Japan)

The story of “M.D. Geist”, member of a league of government-made super-soldiers, that became uncontrollable, is one about violence as the main force within the main character as well as the world around him. Similar to, for example, Takashi Miike's “IZO” Geist is a character captured within a circle of brutality, which has become his main drive, but perhaps also his knowledge this world cannot be saved and thus has to be destroyed. It is a deeply cynical and grim story, in which blood and gore a parts of the palette of a world in where beings such as Geist do the only reasonable thing – do everything in their power to destroy. (Rouven Linnarz)

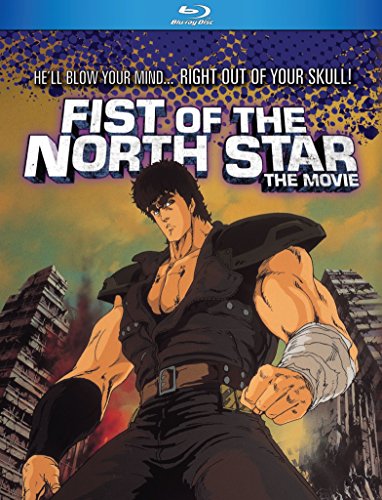

5. Fist of the North Star (Toyoo Ashida, 1986, Japan)

One of the film's most notable elements is its over-the-top violence, a feature that is faithful to the manga but was dumbed down for the series. Fists fly, blood spurts and heads explode (a lot) as our cast of mighty warriors dish out what they consider to be rough justice indiscriminately. Not only does the violence reflect the craving for more adult-oriented animation during the 1980s, it also emphasises the brutality of this post-apocalyptic world. There's something extremely cathartic about an anime that holds no bounds over its savagery and delivers the goods in terms of bloody action. The violence also serves to make the narrative's unexpected resolution far more poignant. (Tom Wilmot)

Buy This Title

on Amazon

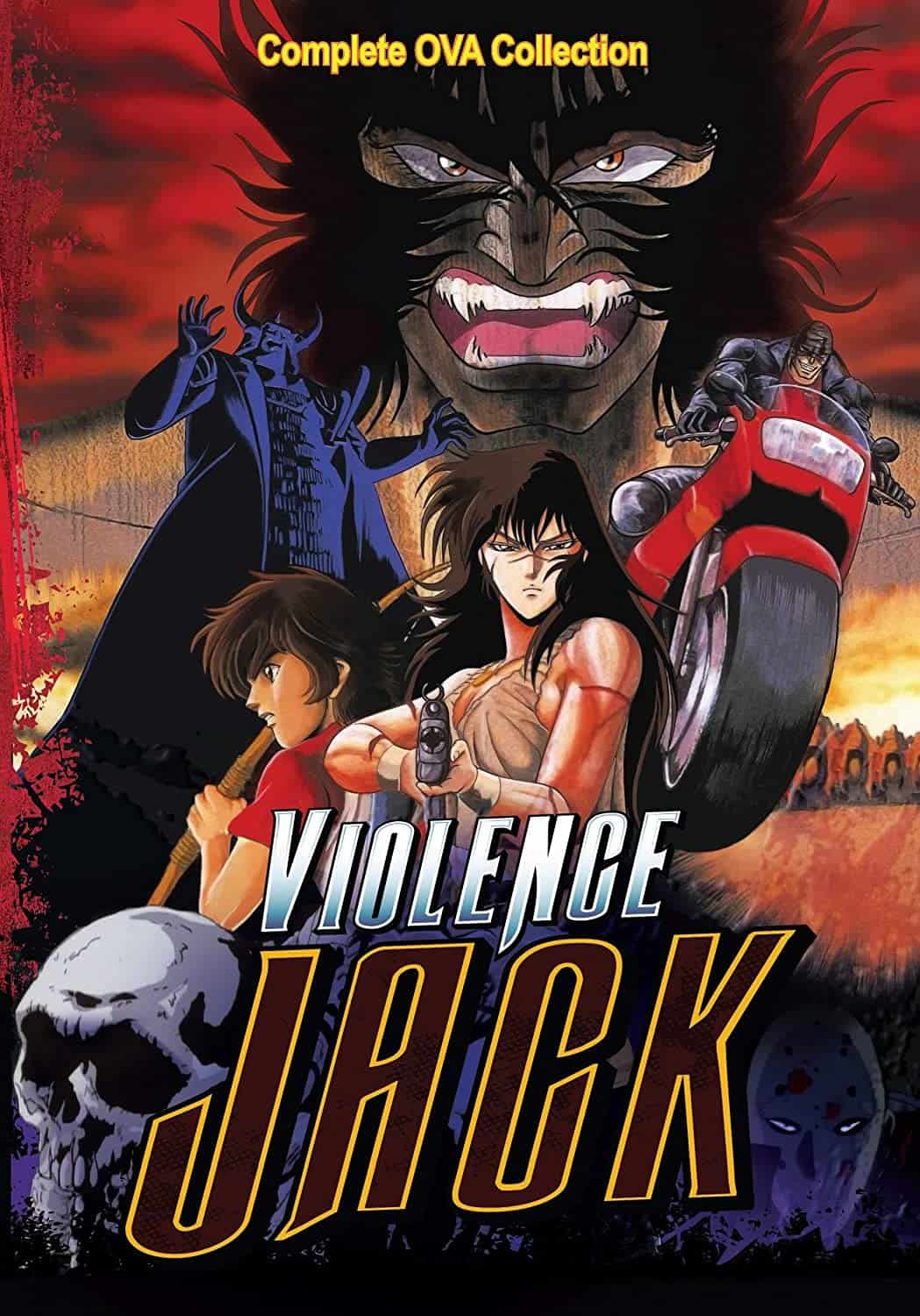

6. Violence Jack: Evil Town (Ichiro Itano, 1988, Japan)

The most controversial among the series' OVAs, “Evil Town” incorporates a number of elements that border on misanthropic, including rape, necrophilia and cannibalism. The Kanto part of Tokyo has submerged underground after a series of major earthquakes, and is completely sealed off from the rest of the city. The survivors have been split in three “regions”. Section A has all the businessmen and white-collars in general, who are trying to establish some sort of order. Section B has all the criminals and sociopaths, while Mad Saurus and his assistant Blue rule. Section C is only comprised of models who have been trapped on a train. Jack emerges in the last section and decides to help the women against the other two sections. The story in here is just an excuse for all the sex and violence, with Jack himself being the zenith of this tendency, as he barely even speaks. In this truly trash setting, though, the animation is quite good and colorful in all its splatter glory. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

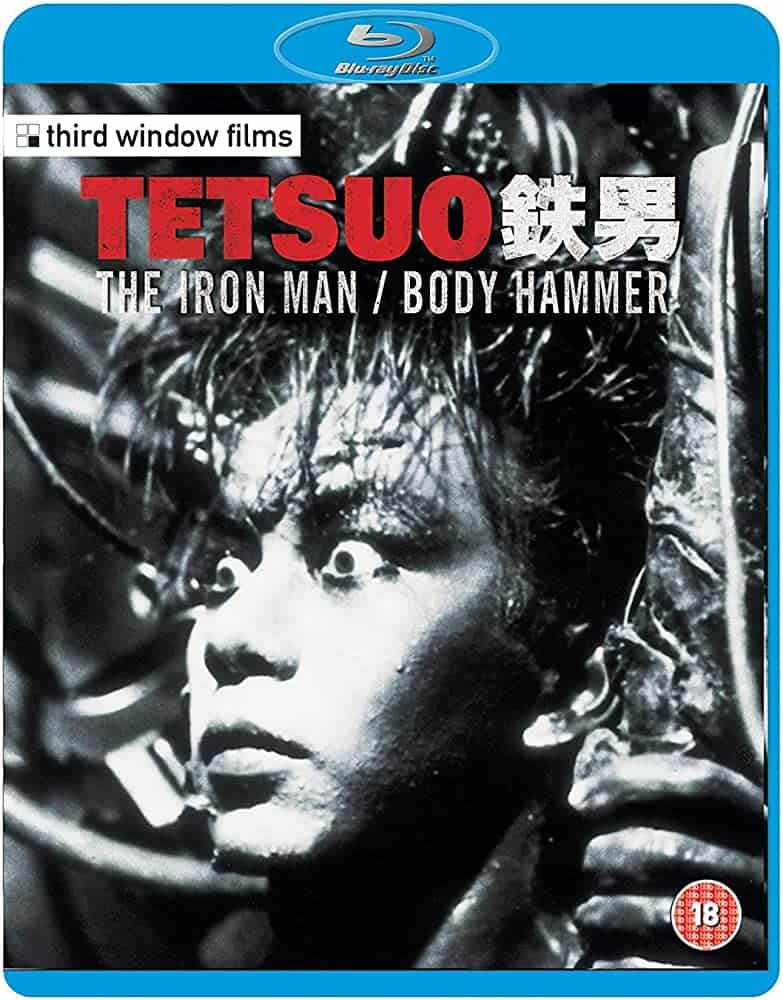

7. Tetsuo: The Iron Man (Shinya Tsukamoto, 1989, Japan)

As the movie opens, we see a lonely figure (Tsukamoto) – a character also named “Metal Fetishist” in some reviews and publications – collecting various bits and pieces of metal from an abandoned scrapyard. Satisfied with today's finds he undergoes a painful operation of placing a metal rod in one of his legs. This is one of many nearly unbearable sequences the first “Tetsuo”-movie has to offer, but beside the gruesomeness, there is far more to it. Apart from its theatrical sensationalism, a way of gripping the audience from the start on, this is a work about fusion, about making a connection of flesh and iron. (Rouven Lin)

Buy This Title

8. Riki-Oh: The Story of Ricky (Lam Noi-choi, 1991, Hong Kong)

On another lever, there is something to be said when viewing “Story of Ricky” in the light of the prison movie-genre. Similar to the “Sasori”-series or even “Prison on Fire”, its brutality and bloodshed can be considered a mirror to a society showing utter disregard for humanity and defined by misogynist hierarchies. While no one would confuse Nai-choi's feature with a prison drama such as “The Shawshank Redemption”, there is an undeniable satirical touch to some scenes and characters, most significantly perhaps Fan Mei-sheng's character whose obesity and insatiable appetite for food, drink and porn (if his extensive “library” is any indication) exposes him as the kind of capitalist predator he is. In this context, Lik Wong/Ricky becomes a true hero, fighting for those without a voice and who become easy prey for the warden and his many goons. (Rouven Linnarz)

Buy This Title

on Amazon

9. Dr Lamb (Danny Lee and Billy Tang, 1992, Hong Kong)

Frankly, “Dr. Lamb” is quite the dark and brutal genre effort. Much of that comes from the story by writer Lau Kam-fai that allows for such an atmosphere to exist. The fact that we get to see who Lam really is with the series of exploits into his personality, shines a light on how he became a killer. The psychological insight gained from a small kid who openly enjoyed pulling up young girls' skirts, spying on his parents having sex, and watching his younger sister bathe herself sets him up as a sexually-repressed deviant capable of the various acts he commits throughout here. This continues later on as we see how they treat him as an adult with a series of utter disdain and outright cruelty that is a part of the dysfunctional family relationship at the core of the film, setting his stage of depravity to come. Being able to engage in the cruelty and sexual deviance that gets brought to bear on the bodies here with the type of uncomfortable setpieces that wallow in grime and sleaze. Given the amount of influence and highly effective detective work that goes on with how the investigation goes along showing the police officers beating and attempting to brutalize him for a confession with all of the evidence they have against him, all give this setup a great touch into Lam's psyche. (Don Anelli)

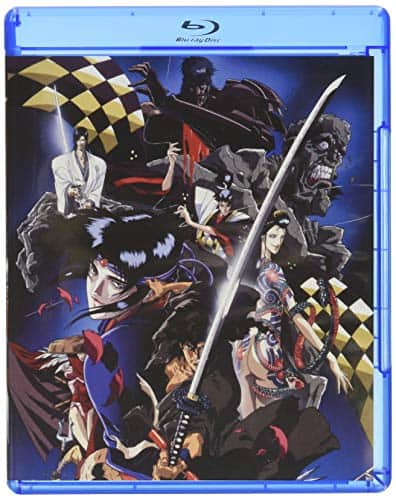

10. Ninja Scroll (Yoshiaki Kawajiri, 1993, Japan)

However, the aspect that gave the film the cult status it retains until today, apart from the interesting but occasionally rather perverse characters and the prevalent sex and nudity, is the action scenes, with “Ninja Scroll” exhibiting a plethora of elaborate and rather violent ones, with the initial one in the bridge, but even more, the one where the first monster faces the group of ninjas, setting the tone in the most eloquent fashion. That the various enemies Jubei has to face differ much in terms of both aesthetics and technique, adds even more to this aspect, also exemplifying Yutaka Minowa's character design. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

Buy This Title