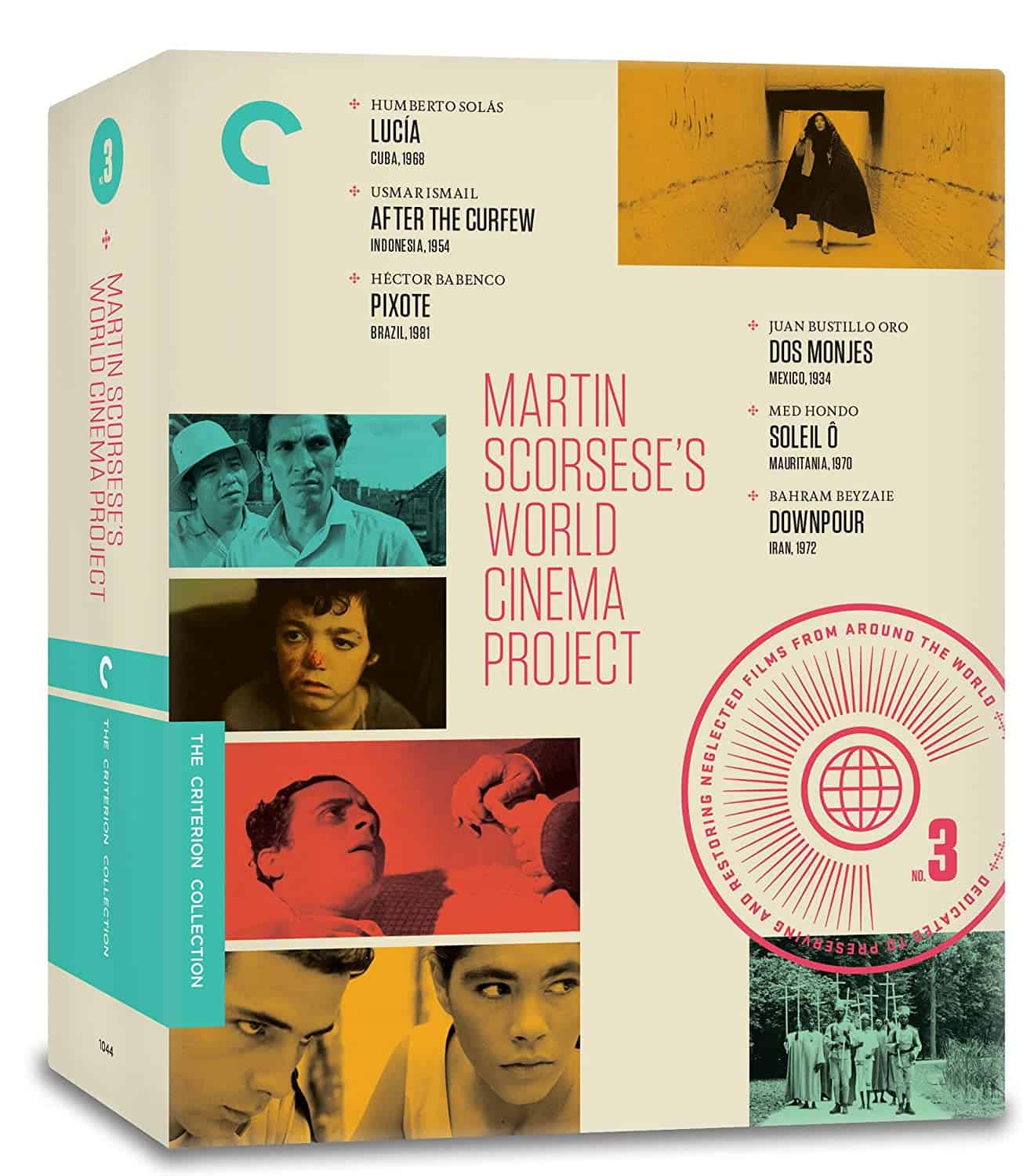

Bahram Beyzaie's 1972 “Downpour” (رگبار) paved the way for the Iranian New Wave, quickly becoming a classic within the movement. The work's original copies were largely irreparable until a 2011 restoration of the film by Martin Scorsese's World Cinema Project. Within this light-hearted but heavily themed neo-realistic drama, Beyzaie expertly explores free will, controversy, and morality within the confines of a community bound by internal sociopolitical norms.

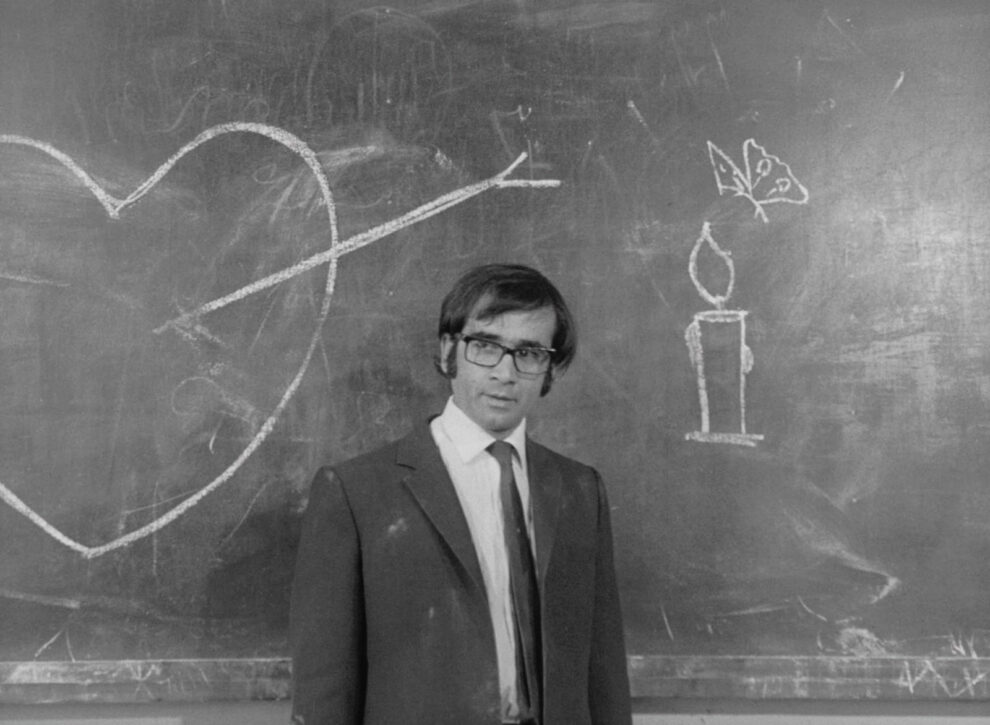

When Mr. Hekmati (Parviz Fannizadeh), a generous but hapless schoolteacher, takes a job at a new boys' primary school, he quickly learns that he has much more on his hands to handle than expected. The moment he meets the hard-working Atefeh (Parvaneh Massoumi), the older sister of a young pupil, he is consumed by a fascination with the young woman. However, he rapidly learns that she is engaged to be married to Rahim (Manuchehr Farid), a mustachioed butcher and man much larger than himself, when he is pummeled by the guffawing fiancé for spending too much time with her. As their budding romance flourishes in secret, Hekmati must navigate the students' love for him, his relationship with Atefeh, and a community that demands conformity.

The gaze of others is the primary dictator of Hekmati's behavior throughout “Downpour.” Adults whisper behind his back while staring him in the face, his students play around in front of him with little regard for his reaction, and he is constantly slapped around, literally and metaphorically, by those with whom he interacts. Atefeh's younger brother Mosayeb is the first to truly prompt and bring up the attraction between the two of them, merely speaking his mind and thinking little of it. However, the other children's mockery of his attraction to Atefeh begins to shape the schoolteacher's perception of himself, transitively accused of indiscretion, as she is to be married to Rahim.

Collectively forced into a public denial of their romantic attraction to each other, they repress their own emotions. It finally reaches them on a visceral level, transforming into a sort of “doublethink” indoctrination that makes both of them question what they actually feel and believe. This constant surveillance and oversight is also demonstrated through a motif of reflections in puddles, mirrors, and shattered mirrors. Hekmati and Atefeh's inability to see this very reflection of the truth about their fate is what ultimately dictates the outcome of their ever-so-brief relationship and co-existence in each other's lives. At least after Hekmati is drunkenly beaten up in a fight with Rahim, he picks up his last shred of dignity: His unbroken glasses that lay unharmed on the ground, representing his determination to return to teach his students.

Fannizadeh excels as the bumbling Hekmati, just naive and charming enough to catch the eye of Atefeh. However, Farid shines as the easily despicable Rahim, transforming him from the schoolteacher's simple foil and villain into one of an understandable passion and self-protection. The children steal most of the scenes at the school, acting as both mediators and a form of Greek chorus. They engage in some of the most enlightening conversations in passing while going about their games and schoolyard activities, even discussing the politics of favoritism.

Swiftly edited by Mehdi Rajaeeyan, Beyzaie makes use of this fast-pace to instill a sense of anxiety aligned with the main character's own behaviors and emotions. In particular, his relationship with Atefeh is shown to be highly governed by the people in their social spheres. They meet prior only in passing once before, but from the first moment he lays eyes on her, he knows in his heart that he has fallen for her but cannot speak, instead shattering a vase in his hands. Their first true meeting in a forest clearing begins separated on two benches, then one bench, and finally, the camera pulls back to reveal that they are in no way alone. All of the students were piled high in the tree branches behind them, listening gleefully to Hekmati professing his love to Atefeh.

In the end, it is not the fight between two men for a woman that ends the possibility of a future between the two protagonists. Rather, Hekmati is seen as a threat because his own innate generosity, optimism, and charm are too powerful for him to coexist peacefully with the politics of the school bureaucracy. But his unbridled determination to strive forward and “keep on keeping on” allows him to shine as the protagonist and the hero of the film. Despite this, the viewer is made to know, deep down, that Hekmati and Atefeh were never meant to be together, as determined by fate and society, who are, in many ways, one and the same.

“Downpour” is not only a must-watch for fans of Iranian cinema, but it is also a lesson in simplicity going a long way. Shooting in black and white, Beyzaie strips away all that is unnecessary for this story, leaving just two people in love and the tragic inevitabilities of life.