At Sundance, tender hostage drama “The Accidental Getaway Driver” was all the buzz – and director Sing J. Lee was at the center of it all. Lee's first feature was nominated for the Grand Jury Prize in the festival's US Dramatic Competition, and also scored him the prestigious Directing Award for his debut.

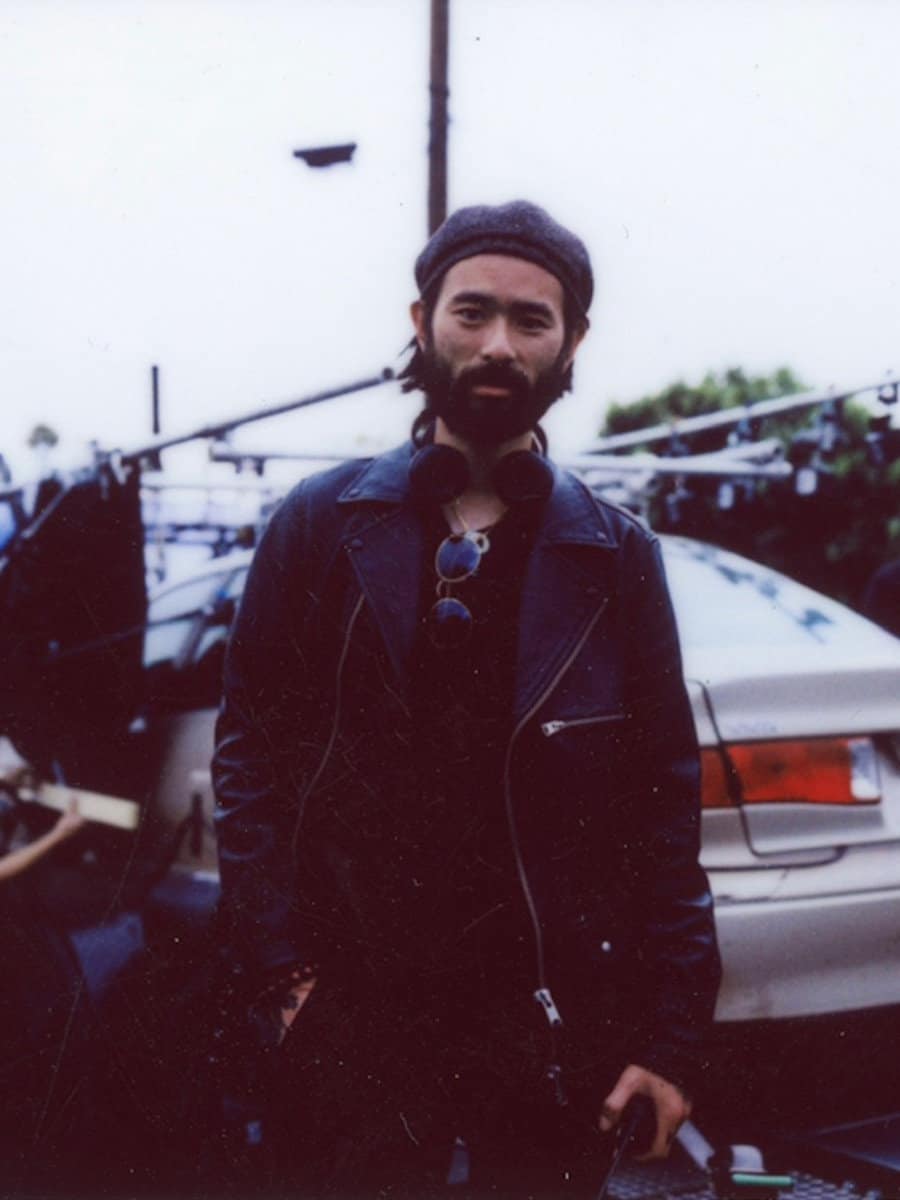

I catch him on the ground before the accolades. Amid the festival hubbub, talking to Sing J. Lee washes one over with a sense of calm. He greets us in a sharp black turtleneck, groomed beard, and a British accent — a memento of his childhood in the UK. Our allotted twenty minutes spill over into an hour as the conversation spans across continents and oceans. Over the tiny tea table between us, I realize that the complexities of his own biography is inextricably tied to the production of “The Accidental Getaway Driver.”

“I can not not be seen as the Other,” he admits. Lee's heritage is from Hong Kong, but he himself spent his earlier days in Manchester and Wrexham, UK. Now, Lee is based in Los Angeles. “This idea of being anchorless seemed like such a devastating thing when I was young. As I got older, I realized that it's a futile practice. It's a beautiful thing to float through and observe so many different places. That functions in the way that I approach cinema as well.”

“That's why you decided to make a road movie,” I quip. “The Accidental Getaway Driver” is based off a real story wherein an elderly Vietnamese cab driver, Long Mã (played by Hiep Tran Nghia here), unwillingly gets caught up in three convicts' escape plan. Lee laughs. The movie is also about the “tender story beneath the surface,” he shoots back. “It's about the fragility of longing, of feeling like not deserving love… It's this observational story of fragmented characters who are searching for the same thing in some way.”

Make no mistake, however: “The Accidental Getaway Driver” shies away from the found-family dynamics of the likes of Hirokazu Koreeda (“Broker,” “Shoplifters,” “Nobody Knows”). Though the older Tây (Dustin Nguyen) and Long Mã grow closer together through their travels — developing a father-son sense of deference instead of their original captor-captive dynamic — legal circumstances keep the two apart.

“Is it alienation?” I ask. Lee pauses. “Maybe more like the impermanence of things,” he answers. He credits his parents' Buddhist roots. “There's this fleeting sense of connection that isn't infinite. These men aren't men, they're children – lost children.”

Despite the narrative themes of effervescence, Lee recounts the long-term relationship-building exercises he would conduct with his cast. He spent time with each of his actors to talk about their personal stories for a year before shooting. “I don't want [my actors] to be vessels of themes or characters,” he says. “As we went through the script, [the actors] integrated their personal stories with each other. Because everyone was coming from such a personal place, that chemistry was real.”

This seems to be a running pattern in this conversation with Lee: observation and anchoring. Lee remarks this was particularly important for him as someone who is neither Vietnamese or from Southern California to develop this story about his characters. He recalls how, a year before the project, he had visited Little Saigon daily over two weeks. There, he staked out at Chez Rose Cafe on Bolsa Avenue, where he would order tea and watch older men play Chinese chess. After a while, one of the regulars, Lee recalls, approached him and said, “Most of us aren't friends here. But we come down everyday because we know we'll be here. Perhaps we're just companions. We spend some time here and then we go home.”

“This stayed with me,” Lee confesses. “I wanted to honor these [chess-playing] men.” After finding out that the one he had been in contact with passed away, he decided to weave in chess-playing figures into Long Mã's peaceful backdrop. Literature, Lee notes, also played a big role – especially “The Gangster We Are All Looking For” by Lê Thị Diễm Thúy. The movie seems to be a collaborative effort in Lee's eyes. After extended conversations with the author, he ended the film with a line he developed with her: “Don't dance in place of your shadow. Dance with someone new.”

Even with all these cultural specifications, there are “more similarities than we think”, Lee notes, between his own background and the Vietnamese American community he interacted with and filmed. “When you've journeyed somewhere else — whatever culture that may be — you build an enclave somewhere, a time capsule of a culture. There's a tragedy to the time capsule. But the life that forms in the ashes of that — the identity and generation that arises — you beget something beautiful. [Diaspora] is an interstitial space between two hubs, something you want to retain so you don't become an abnormality.”

This approach shaped Lee's own ideas of the script, even as it was written in a different language. Keeping the time capsule idea in mind, the three generations of Vietnamese men in “The Accidental Getaway Driver” — Long Mã, Tây, and Eddie (Phi Vu) — speak with their own generational nuances. Vietnamese notes of endearment escape the English subtitling as well. Long Mã and Tây refer to each other in affectionate, father-son terms that escape translation. Long Mã struggles to speak English, but is remarkably perceptive in Vietnamese. These details, Lee remarks, go back to his own interactions with his parents and grandparents. “The language barrier constricts you from saying what you really want to say in this country. This wealth of stories, the poetry — if you just pay some attention, you will see all that remained invisible before. Every time our generations pass, we lose a bit of insight, our stories. It's a whisper and then it's gone.”

One of the few ways the stories carry on, however, are through food. When Tây swings by his home for the first time since his jailbreak, his loved ones receive him as one of their own. The camera lovingly engages in a series of extreme close-ups of chopping boards and boiling bones before it returns to the dinner table. Conversations about what they should cook, apparently, had been a hot topic of discussion. Lee describes how the Vietnamese crew members would share their own familial versions of the dish; he details how they tried to locate the Goldilocks medium of “not too humble and not too lavish.” In the end, the crew settled on a version that they thought would fit Tây's family.

For Lee, this close attention to food is personal as well. He connects the dots to his parents who ran a Chinese takeaway shop in Wrexham: “When I look back, I see the romanticism of [the takeaway they ran]. It's literal fire and food and culture that they passed on to other people, to put food on our table.” Though at first he saw cinema as a mode of “escape” from his day-to-day — engaging in cinematic movements like Taiwanese New Wave (he gushed over Edward Yang's “Taipei Story”) and British Kitchen Sink Realism — he now finds “parallels” between his life and work. “There's a beauty in the mundane and the ordinary,” he says with a sparkle in his eye. “When you can go to someone you love and have a nourishing meal – that's sustenance to the spirit. That's love.”

As our time together came to a close, Lee tells us his plans for his next two projects: exploring themes of longing and belonging. “But I feel like that's something I haven't finished exploring yet. Maybe I won't,” he finishes pensively.

“Well, maybe that's something we will never finish,” I reply.

He chuckles. “That's right. We are all on a journey and we're always discovering.”