“#LookAtMe” is the sophomore feature by Singaporean director Ken Kwek, and premieres at the New York Asian Film Festival. In it, twins Sean and Ricky Marzuki (portrayed brilliantly by yao) are small-time YouTube pranksters ready to trick their mother Nancy (Pam Oei) for some views. The problem is, no one is watching. One night, Sean is invited by his girlfriend Mia (Ching Shu Yi in her feature debut) to attend her church. There, he witnesses an extremely homophobic monologue by Pastor Josiah Long (magnificently flamboyant and detestable Adrian Pang) that openly vilifies people like Sean's gay brother, Ricky. Angry at the pastor and his congregation, Sean makes a fiery YouTube video making fun of the pastor. The problem is, homophobia is somewhat permitted due to Section 377A of the Penal Code of Singapore, which criminalizes sexual relations between men, while fighting it openly is not. This brings numerous problems to Sean and his family.

“#LookAtMe” is screening at Vesoul International Film Festival of Asian Cinema

The characters inhabit a Singapore that is empty and devoid of almost any life. Its streets are deserted, the parks cold and uninviting. Even the apartment of the twins and their mother feels somewhat alien, as if not theirs, not lived-in. They are all like a set of a massive reality show. Simulacra whose aim is to betray their own unreality. This manages to convey the extreme alienation citizens, especially those who don't fit in narrowly defined identity expectations, experience in the hostile city-state.

The characters who are unlucky enough to live in this surreal Orwellian city are constantly observed by the all-seeing eyes of the state whose subject they are. Kwek makes sure to remind us that, by focusing his lens on the cameras that are everywhere in Singapore. In the empty parks, above the deserted streets, even in Sean's prison cell which feels like coming out of “Big Bang Love, Juvenile A“. The whole country is a place of absolutely no privacy and freedom, a huge prison cell with only so slightly more flexible borders.

The cameras aren't the only things that observe the country's subject for committing offenses such as gathering on the streets. The portraits of the leaders of the country that adorn the walls of every institution are much worse than that. Depicting an elderly woman and man with stern expressions, they remind the viewer of the North Korean leaders, rather than those of a free country. Their only function is subjugation through fear of authority.

This all, the alienation, cameras, and all-seeing eyes of the leader himself, create a very surreal and dystopian atmosphere. As if all the state-supported homophobia by the pastor is out of this world. And to a degree, it should be, because laws like the century-old Section 377A of the Penal Code have no place in the modern society. A part of the runtime even depicts some of the fight by Ricky and his peers against the outdated law, and even their light hopes of finally changing it. But as Hossan Leong says in a brief cameo as Sean's lawyer, there is no chance of winning. In fact, losing is a given; after all, he's lost all twenty LGBT cases he's taken. But the point is to fight against such outdated laws which normalize hatred.

What is even worse, they give power to people to use hatred and deny the victims the right to defend themselves, be it with words or actions. The law, and a big part of the society, as the movie makes clear, sees one type of actions (the dehumanization of the LGBT community) as rightful and normal, while the other (any type of standing for the rights of the same community) as a political act, and as such – illegal. This renders the victims even weaker, because it robs them of their voice and the opportunity to be heard, not to say to fight back against the attackers.

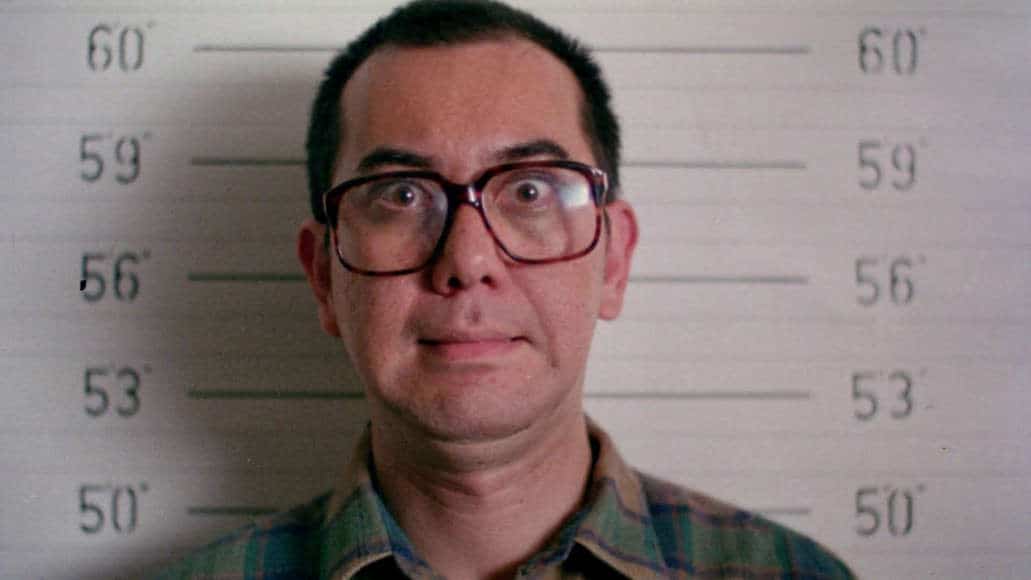

We see this best at the beginning, when Ricky and Sean visit the church together with Mia and listen to the hateful speech by the pastor. This, by the way, is the only scene devoid of the surreal atmosphere that permeates the entire film. Instead, it is grounded and insanely realistic, from the cringy music at the beginning to the passionately homophobic speech by the pastor. It's as if taken from a real video by a real church leader. Flamboyant and “cool” looking, his rhetoric is as if coming from thousands of years ago, and it sounds like it will never change. Both within this specific church, but also the church as an institution. It is difficult to watch, and the fact that he is allowed to speak like that in front of thousands of people without any repercussion is detestable.

Were “#LookAtMe” a Hollywood movie, or a cookie cutter big budgeted stuff, Sean and his family would've won at the end. They would've not only re-appealed the young man's sentence, but even manage to change the law. But this is not that type of movie, it is a tragedy, instead, in which no one wins. Not Sean and his family, not even Mia, not even the pastor. This makes it all the more worthy watch.