Born on December 11, 1991, Mikhail Red is an independent Filipino filmmaker based in Manila, the Philippines. Growing up under the guidance of his father Filipino filmmaker and Cannes Film Festival Palme d'Or winner Raymond Red, Mikhail was exposed to the cinema at an early age. He wrote and directed his first short film at 15 and immediately earned recognition in local and international film festivals. As a young up-and-coming filmmaker, he continued making short films throughout his teenage years, screening his works at film festivals in Hong Kong, New York, Berlin, Seoul, Austria, and Canada among others. At 21, he wrote and directed his first full-length feature film entitled “Recorder”, which had its international premiere at the 2013 Tokyo International Film Festival. Since 2016 and the success of “Birdshot”, he has been shooting a film a year, most of which were box office successes.

On the occasion of his presence in the International Jury if FICA Vesoul, we speak with him about his movies, his career, his upcoming collaboration with Viva, “Arisaka” his dream projects, and many other topics.

Roughly half of your movies take place in the city and the others in the country. Where do you prefer to shoot?

Now that I think about it, the reason this happens is because ‘the grass is always greener on the other side'. When I am doing a city movie, I miss the countryside, the nature, you miss doing exterior shots, since it can get suffocating in the city. When I am in the jungle or in remote areas, it is very tough facing the terrain and the weather for example, so then I start thinking, “Man, I miss shooting in the city, with air conditioning…”. That is why my filmography alternates I guess.

Regarding the logistics, though, which do you find easier to do?

They both have their own challenges, but it is usually easier in the city. When you are shooting in the country, you have to bring everyone there, you have to house everyone in hotels. And even when you are in a hotel, the actual shooting location can be hours away, and you have to bring everyone there. Also if something bad happens, during a stunt for example, the hospital can be hours away. The most annoying thing is the sun. In the Philippines, it is always so bright and then a cloud passes through, and it is overcast and you cannot continue shooting because the scene would look inconsistent. Also people are slower when it is hotter. TIme is more important when you are shooting in rural locations. On the other hand, you immediately feel that these settings are more cinematic, when you are outdoors and in nature. It is hard to make a cohesive aesthetic in the city, it is very chaotic.

You have been shooting essentially a movie per year for quite some time. Do you feel the need to maybe take a break?

Definitely, but to be honest, the reality in the Philippines, considering it is a third world country, is harsh. The budgets are smaller and the pay is smaller. It is very rare to have filmmakers that shoot exclusively feature films as a career. You make feature films and then you make commercials, you make feature films and you have a company, you make features and you also act, you make feature films and then you shoot for TV. There are only a few of us that only make feature films. Realistically, it is really hard to shoot, for example, one film every three years and that is all you do. You are not going to make rent in that way, it is almost impossible. It is not like Hollywood, where someone is in Sundance, then they make a big movie and that's it, they are made for life, they never go below a certain budget anymore. If you notice in the Philippines, you can be an A-lister festival filmmaker, and three years later, you are making movies with five days of shooting again. You are always trying to keep your head above the water, no matter how big you make it. You are always as good as your last film, always trying to prove yourself.

Check the review of the film

So it is a necessity to shoot a lot if you want to sustain yourself financially.

Just with filmmaking, yes, and if you stop, it would be hard to get back to the financing circuit. They forget you, and there is always another filmmaker who can do it. Also, I guess what happened was after “Eerie”, things picked up. “Birdshot” and “Neomanila” are films that you can go to markets with, you can get 10,000$ here, $20.000 here and it takes you three years to make a movie. But when you make that movie, you already have the support, it is easier then to get the festival traction. But after “Eerie” which was more of a financial success, it is more networks, studios and streamers that will come to you and ask if you have another idea. The process changed in a way that financing was faster but of course there is a time window, you need to deliver in a year for example. You cannot just do post-production for three years. There is a certain structure to it.

Have you now reached a point that is easier to raise money for your movies?

Definitely, especially if you saw the recent news, after “Deleter”, we are setting up a production company, called Evolve Studios. I am very happy because the capital will be coming from a local studio, Viva, who is now the most active in the country, having done “Deleter” and “Buybust” among others. Especially after the government shut down ABS-CBN that did “Eerie”, there is only one top dog in terms of feature filmmaking and because of “Deleter” they want to invest more in genre cinema. The film showed that there is an audience for movies beyond romantic comedy and drama, so when they saw that horror, thriller, mystery could do well, they asked me to set up something, and it is co-ownership essentially and that is quite rare in the Philippines, to get profit share. It is not just the money, it is the idea that they believe in you, that even when they fully finance something, you co-own it. This happens very rarely, even with my earlier films, whoever financed it owns it. This really changed my perspective, I would never set up a studio, it is something of a far end game thing.

You will be producing also?

Yes, so I don't have to direct everything which is also exciting because there is this noble feeling that you have the opportunity to create a shift towards a diversity of the films being made to make sense for them to finance them. Yes, we want to be creative and push boundaries and diversify the options even for the local studios. We want to show to the people that finance these films that it makes sense, that it is sustainable. I think that is the challenge; a lot of young filmmakers of course get their name out there in festivals, but after that, it kind of slows down, people don't go after your third film. They give more opportunities to first and second time filmmakers and after that, they sort of get lost. I think it is a good start, and I think if we do it slowly, step by step, we could build the taste even for avant garde films, we could build the audience locally. And as you build that, you also have that international buffer where we make films that have the quality to go outside our borders, because horror movies can be more universally appealing. We are starting late this year and we might shoot in Australia and the Philippines.

Will you be producing or directing?

Right now it could be both but we will see, because we are still open to having other people direct.

To go back to your movies, could you tell me a bit about the inspiration behind “Arisaka”?

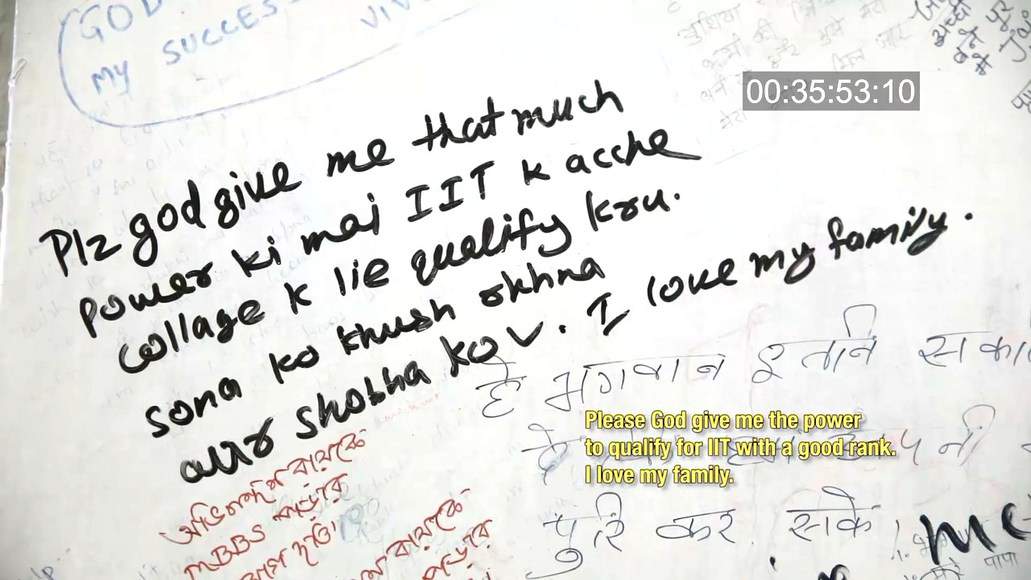

It happened during the pandemic and took us all by surprise. I really wanted to shoot a film no matter what and the people at the time were doing screen-life and Zoom movies for example, because they had this creativity they wanted to channel, and that is the only thing they could do at the time. Either small scale Boys Love (BL) stories because it is logistically easier to have two characters and rely on their love story and chemistry, while it is an interior setting in screen-life. I wanted to shoot something more ambitious and a bit bigger but still Covid-safe, outdoor, with very few characters, because there was a specific headcount. Very few dialogue also, like “Revenant”, I always wanted to do a survival thriller. One of the biggest inspirations was an article I saw during the pandemic, where the Aeta community living in Bataan would find relics from the war, old weapons from the Japanese, and they would repurpose them. Along the production designer, when we went there to cast, not actors but just people of the population, they showed us some of these relics and they had almost redesigned some of these weapons into hunting rifles for example.

Then there is this strange feeling of violence that has been plaguing that area for years, even until now it seemed that they were being invaded, but this time by our own authorities. There is always a land dispute going over there and they are being displaced. It almost feels timeless, this cycle of violence going on in that area. At the time, we had a very militaristic response to the pandemic and people were scared of the police and if you look at all my movies, there is always this fear of power, of authority. We wanted to do something that would be close thematically to all of those films, but at the same time, do it differently. Very minimal dialogue, more moodiness and more survival thriller, against rain, against time, against the police hunting you down and then being saved by the local Eita community.

Check the review of the film

Can you tell me a bit more about the casting?

This time I wanted a non-actor, I always do that in my films, combining an experienced veteran and a new face. We auditioned first thinking of a boy and then she, Shella Mae Romualdo, actually auditioned as one of the sisters in the family in the hut and she was so bright and charming and immediately played with us doing a scene for the camera. She mesmerized us and caught our attention so we decided to change the script for her. After the film, even Zig Dulay casted her for “Black Rainbow”; she is a natural, she could cry on queue, she was very in touch with her emotions. It was basically a miracle that we found her in that community. And we paired her with Maja Salvador whom you typically see as a pop star. She did drama, romance before and she is a dancer and singer. We thought of deglamorizing her and make her say nothing and have her be against all the elements. And pair her up with someone who would assist her, and would be from the area and know the location. But there is a language barrier so the interaction is very physical, the chemistry of the characters is very physical.

Can you give me some more details about how you shot the movie?

What I just mentioned was the objective challenge and we wanted to do everything practical as well, like with live fire. This was of course pre-Alec Baldwin scandal, now it is scary and to be honest, it was pretty risky. Even in my older films I preferred live ammunition, blanks. When we shot the car, that was real, but of course we shot everything with an armory and firearms expert. That is another thing I always do as a filmmaker, of course I want to tell a story and explore a certain theme but at the same time, on a technical level, I want to do something that I have not done. I use every opportunity I get and any project I deal with as an opportunity to learn something and try something new. In this case, I thought that we did not have many shooting days but I wanted to experience mounting a scene, the opening itself. To put more resources there and do things practically, I wanted to see how we can combine the rain, the bullets, the car getting hit, all of which were mounted practically. It was tough but I learned so much from that. The crazy thing is there was a storm, one of the biggest typhoons of the last fifty years and it hit us right in the shoot. And we had to finish because all the crew and equipment were already there so we used the weather actually. That was the challenge, I wanted to be more ambitious and do everything for real. It was tough, I don't know if I could do that again. I wanted to shoot a “Revenant” without the “Revenant” budget.

The shoot was very linear, it was like a journey, also for Sheila, in order to experience that journey with us and get to that point where her emotional release feels almost like a catharsis. By shooting it almost in a linear structure helped in that regard.

Was she ok with all that that you had her do, considering her previous works? Essentially she is close to an animal in this movie, was she ok with her image being like that?

What I always try to pursue is for any project not to only be exciting for me but also exciting for everyone else. You can really feel that on set and I think that this is what sometimes attracts these actors in my movies, people who are really big in the Philippines, people who have cell phone billboards in the highways. I think they like to do these projects because it is not their norm, it is an escape for them to try something different. It is really rare actually in the country, a polished genre movie but still have that international sensibility to travel abroad etc. They find it extreme, because it is rare for them to explore projects like that. Whenever an opportunity like that comes, they are actually pretty cool with it, they give their all, they even try to change their look for you and they are very passionate about it. I think that also contributes to its success, locally at least, because it is always a novelty, it is always fresh, this popular actress and dancer acting like an animal, it is surprising for the audience. I try to do that with my films, always trying to create something new in terms of the performance or the characters for example. We try to break the image you have in your hand and I think that always makes it exciting, that is why most of my films have almost a whole new cast every time.

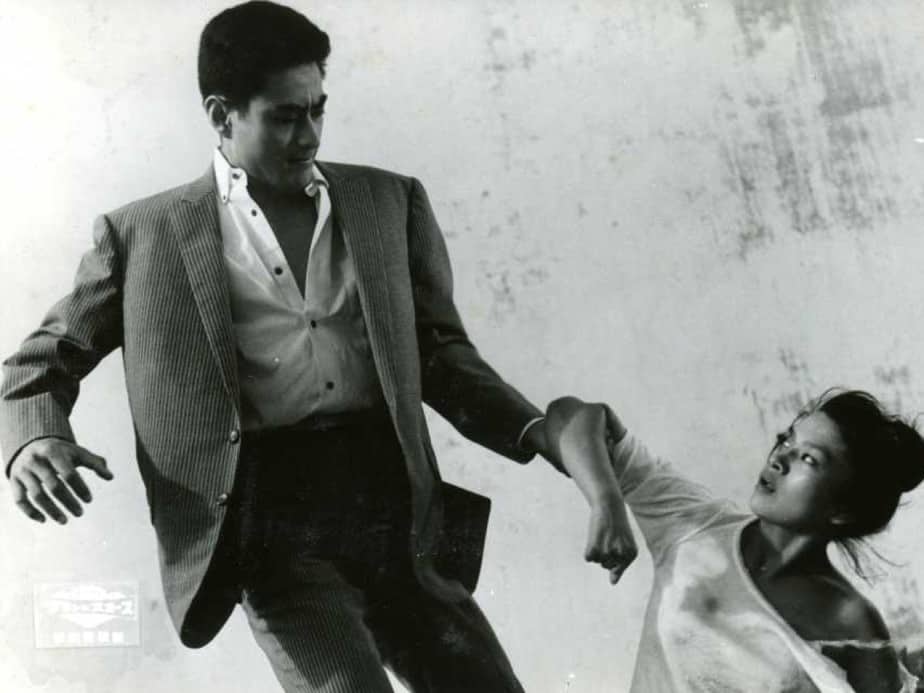

Can you tell me a bit more about the choking scene close to the end?

It is always hard to make it look real, there is a certain way you have to hold the throat in your hands (shows with his hands). I think Maja really sold it, like when we were shooting it. As I said, we shot linear, even the fight scene. We shot the whole scene bit by bit and if you pay attention to the sun, it was changing. By the time they finished, it felt as if it was already sunset. When they were fighting and choking each other, we had to do repeat takes, and she never lost her composure, maybe because she is athletic as a dancer, it worked out for her, the physicality of the role. She could really sell it with her eyes, and that was tough, I don't know how she managed to portray that pain. Maybe it was physical exhaustion from shooting 5-6 hours. We actually had to reshoot the very ending of that sequence, because it got too dark.

How many days did you shoot in total?

Around 17. During Covid, it was strictly up to 12 hours. Believe it or not, in my previous movies like “Birdshot”, we could shoot for 20 hours or more. Even though we had a few more days compared to our usual time, since average Filipino films shoot 8-12 days, it still felt very tight especially with the typhoon. It is so easy to imagine a scene, but when we got to shoot it, how do you do a second take of a scene like the first one, with the machine guns and the bullets on the ground and the holes on the vehicle? The reset takes an hour, that is what you realize. But the cool thing is that by doing films like that, it is not just me learning, you kind of get experience points for everyone on that set, in every department. You are all growing together.

And about the ending, I felt like a sequel is in the works.

Really? For me it is a finished story, you don't know if she is going to make it, if she is bleeding out. Suddenly the meaning of that landmark, the memorial stone, changes for her, now she gives her a push to move forward. WE just wanted to keep it ambiguous, almost like that cycle scene. We just lingered on that scene and just put the credits there and she just kept walking, for about 20 minutes, throughout the ending. And the rain in the end, it was not planned. It was our last day of shooting, and the idea was to have a sunset, a majestic sunset. But then it started to rain and I was thinking that the continuity was gone, since we had no time to call everyone back and redo the scene, so we just ran with it, we just added CGI lightning. That kind of sold the effect, although at first we panicked. For me it was almost poetic, like the sky is crying (laughter).

And that whole place actually has a lot of houses now, it is very populated, it does not look isolated anymore. If you pay close attention to the timeframe, it is almost 2010, if you look at the cellphones, it is loosely based on the Atimonan massacre where cops killed each other on the highway.

You are also working on the third season of “Halfwords”?

We finished post-production. It was quite an experience. The problem is that we got hit halfway by Covid so we had to do three shooting legs, it almost felt like being overseas workers. We all lived in a hotel and we had this quarantine bubble, where no one could go home because we needed to keep the immunity. We were shooting three times a week but everyone went home to that same hotel. It was tough, especially for something so ambitious with world building and swordfights. I guess the experience there was that we had to shoot almost like a film, we should have done it more linear, but Covid changed the schedule, there were supposed to be foreigners coming, so that got a bit more complicated. It was a very challenging shoot realistically due to the circumstances we could not control. I would say just with that project alone, experience points wise for everyone involved, we went to so many genre aspects we had not before, like mixing CGI set extension, big sword fights, we went to an island and all these sequences we do not normally do. We had a tournament, an underground fight, scenes that I would probably never get a chance to shoot. By doing that, I felt everyone involved now has more experience. I really hope it will get released soon.

You have already collaborated with Netflix, Amazon and HBO. Is Disney up next?

They asked me to pitch. It is interesting actually because Disney is expanding. It is funny, because the other day, I was looking at some commercials and I saw Disney+ “The Boston Strangler”, about the women who started the investigation and eventually made the breakthrough on the case. It felt weird having Disney do a serial killer story, therefore you can see that they are trying to expand, and they are doing well in the Philippines. I guess at some point they will connect with local filmmakers. Some filmmakers have this very specific identity or auteur touch, but I guess that I am always trying to do something new, and to the eyes of the streamers, this makes me as someone who can execute a certain genre. And if you have that quality, you are usually on that list. My dream is a remake of Darna, our national super heroine. It has never been a movie, even Erik Matti was supposed to do it but eventually went to TV. It is very rare even being on that list, you need to have experience as a director that can execute a certain level of genre. There is that side to it. I hope that I will have fun with all those diverse projects.

Check the review of the film

So that is your dream, shooting a superhero movie?

From our POV, there is a special feeling about this project because these productions are rare for us in the Philippines. We have a lot of commercial movies and filmmakers who are doing really well in the international circuit. But when you talk about an impressive spectacle genre like Darna, a symbol of hope and a national super hero, it is rare to do that properly. It feels like a dream, as a filmmaker. So yes, that is on the list, but I have other stuff I also wanted to do, like the one we coined as American Serial Killer in Manila. That is one of my oldest projects, it is almost the same age as “Birdshot” In fact, when we submitted it to the Doha Film Institute, that was the first one I tried, they seemed to want something less dark. That was an urban legend essentially, regarding the Black Dahlia who killed Elizabeth Short in the 40s. The prime suspect, the surgeon, went to the Philippines, stayed there even during the era of martial law, and people were disappearing at the time. There was this case of Lucila Lalu, the chop chop lady and the MO was pretty similar. The legend is that for almost three decades, an active American serial killer was in our country and we did not have that culture of serial killers and supposedly the perpetrator had a position of higher power and took advantage of the political situation and the chaos there. That was one of my dream projects and I tried looking for a budget internationally. I went to a number of film markets and tried to get all the resources. But it became more expensive because it is a period movie and it is hard to recreate the 60s and 70s. Now I adapted it and made it with a more modern POV and that being a cold case, so it is more feasible and more grounded because you don't have to recreate the specific time period, it is more like “Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” style. We try to repurpose it

Have you started pitching for that?

I don't want to go straight to the studios because I feel it is the type of film that needs a bit more help, needs more budget, it might not make sense with local financing. You have to understand that the reason that there is a ceiling to the budgets in the country is because it is mathematically almost impossible to recoup it, with the amount of actual paying audience that exist. Even if every middle class person who has the money, almost $8 for a ticket, there would not be enough people to make it make sense. You always have to partner up with someone outside of the country if you want to make it that big, three times as big as “Arisaka” for example.