That three out of the Top 13 best Filipino Films listed by Asian Movie Pulse from the period of 70s to 80s were directed by Marilou Diaz-Abaya already speaks volumes of her singularity as a filmmaker. Discomfiting, dissenting, disturbing are just some of the characteristics that could describe her body of work, but they could also just be characterized by this statement: death to the patriarchy.

This, and shame to women's own internalized misogyny. Abaya was inexorably critical of enablers even before this word became ubiquitous in contemporary online spaces, exposing the chain of relations and connections which destroy, downplay and dilute a woman's identity. Concomitant to this is her questioning of false dichotomies and relentless encouragement to go beyond convenient labels, an audacious and necessary pursuit which she did in films that pushed the Filipino to question dominant and trite narratives about his own history.

Below are just some the films that showed Abaya's voice:

1. Moral (1982)

Abaya, in the 1983 documentary “Visions: Cinema – Film In The Philippines” said that she has to give the Philippine's censorship body the master negatives of this film following objections from the Armed of the Philippines over the way they were depicted in it.

The Philippine military and just authorities in general were included in the story because one of the protagonists, Joey, falls in love with Jerry, an activist. The film effortlessly mixes the political with the personal, as it weaves issues of workers' rights, women's agency over their bodies, homosexuality with the ebb and flow of the friendship among four women, Maritess, Joey, Sylvia and Kathy. This bond remains constant and overpowers everything, even the toxic masculinity that they encounter in their lives. The women of “Moral” are unapologetically political, sexual, flawed and emotional. What makes “Moral” a cornerstone of feminist filmmaking is that even when women are romantically tied to one man, their respect for each other as a woman and as an individual is kept intact and even strengthened by the fact that they do not let this in any way turn this into a license to destroy each other; on the contrary, they lift each other up, telling the world that their identity is not and will never be shaped by a man, even the one they love.

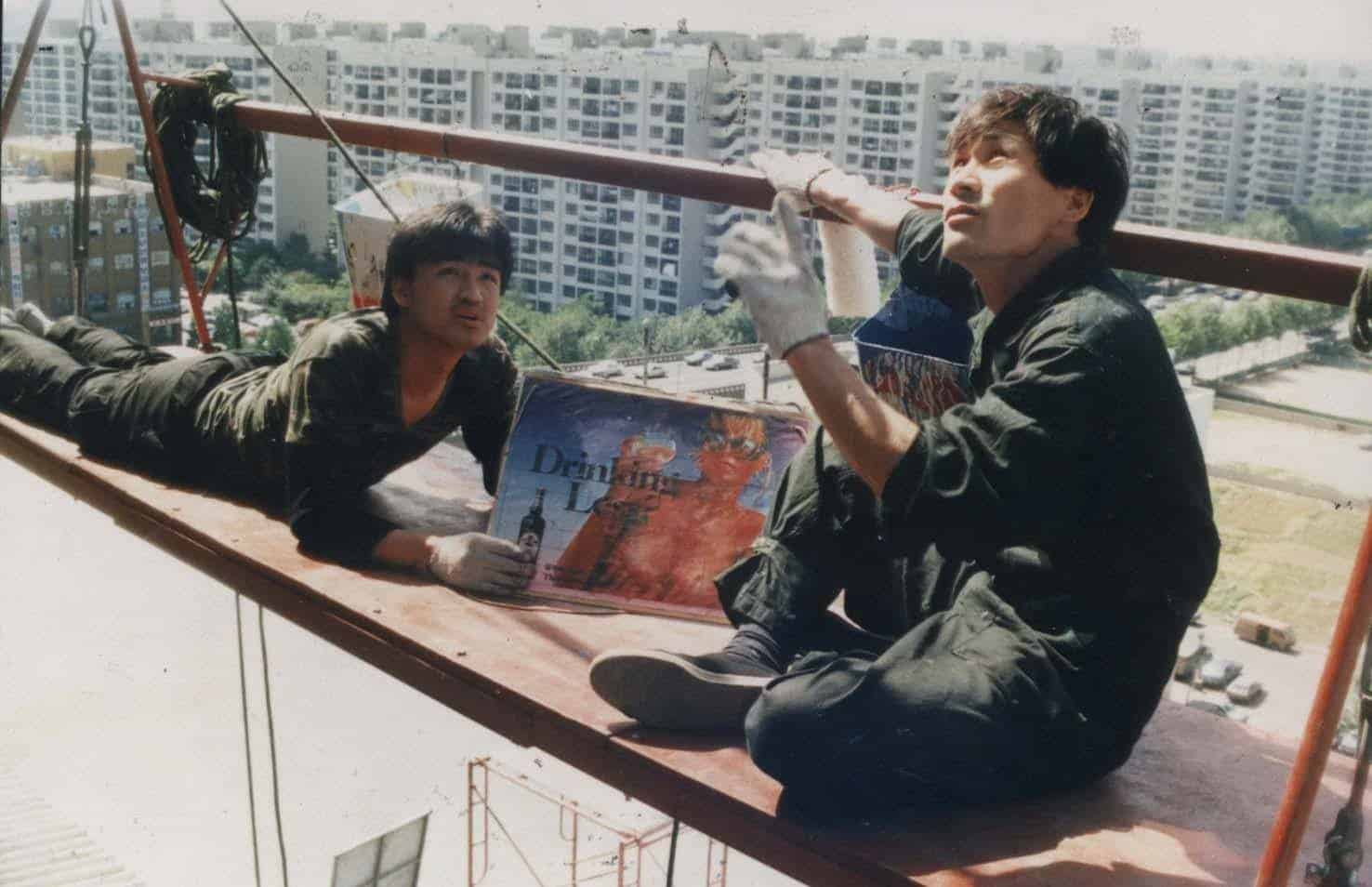

2. Brutal (1980)

The three lives of the female protagonists here – Monica Real, Cynthia and Clara Valdez are all connected by a crime. Clara, a journalist, tries to write about the killing of Monica's husband and his friends, but as she digs deeper into what really happened, she finds out that it was Monica who was proverbially killed first before the bloodshed took place. Monica already lost her self from the moment her own father and mother subjected her to sexual abuse by ordering her to marry her own rapist and to just endure the injustice she experiences in the hands of her own husband and his friends because she is a woman. The film eviscerates traditional gender roles, showing how a woman gets destroyed first and foremost inside her own home, by a family shaped by patriarchal ideals where men are god. It also, however, goes beyond depicting women as victims – on the contrary, it shows their liberation and fight for emancipation. It's a fight that is not is always won, but women will continue to wage this war nonetheless.

3. Karnal (1983)

Karnal, the third installment in Abaya's loose trilogy of films following “Brutal” and “Moral”, shows how men compete for power even within their own families, with this assertion of superiority done through devaluing a woman's worth and dictating who she should be. The men competing here are Narcing and his father Gusting, with Narcing's wife, Puring, damaged and destroyed in their tug-of-war of dominance.

While “Brutal” illustrates how a family could kill a woman, “Karnal” decodes how it takes a whole village to bring down one. Set in rural Mulawin, the film maximizes the backdrop as a breeding ground for the most backward of perceptions and expectations about women, its nook and cranny teeming with tongues which speak against them and of thoughts which justify such culture of misogyny. Puring's deviation from such culture is seen as a threat to their norm and their identity, so they become a willing tool to her dehumanization. But one thing they didn't expect is that Puring will resist and fight back.

Check also this interview

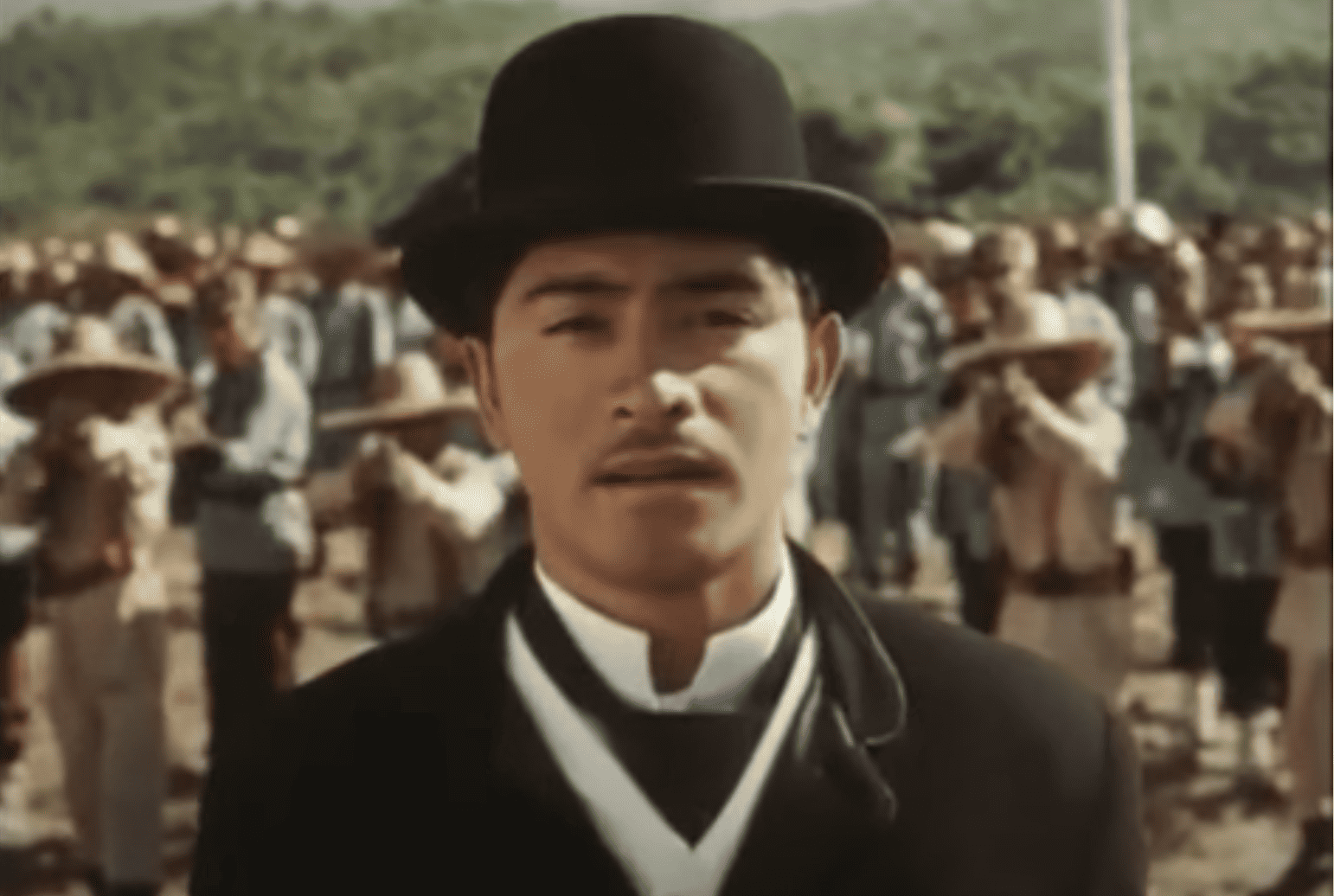

4. Jose Rizal (1998)

A masterpiece in production and storytelling, Abaya neither apotheosizes or vilifies Rizal, the Philippine's national hero. She instead tries to delve into the psyche of the man, one that is shaped by the events that changed his nation, by interspersing his motivations and humanity with the lives of the characters he formed in his literary gems “Noli Me Tangere” and “El Filibusterismo.”

The cinematography and the use of flashbacks punctuate the inflections in Rizal's personal musings as well as serve as a harbinger of the momentous developments in his novels.

As the audience gets to know who he is – a physician, a genius, an artist, a rebel – they also get to witness the unraveling of institutions such as the Catholic Church and the government. These institutions, under the 400-year Spanish regime, were the backbone of tyranny and the oppression of the Filipinos. The film emphatically and deftly tells why without being didactic, hence making “Jose Rizal” more than just a look back at history, but a convincing reminder that freedom is something people have to fight for.

5. Bagong Buwan (2001)

This film courageously invites people to understand that the Moros or Filipino Muslims have a history and identity of their own. It tells the story of Ahmad, a Moro doctor who has to go back to his birthplace in the southern region of Mindanao after his son Ibrahim dies in an attack from vigilantes. Ahmad, unlike his brother Musa, chooses not to rebel against the government and take up arms in their call for independence for the Moro people. However, various events unfold which make Ahmad see why a rebellion seems the only means they have to achieve their desired ends of secession.

The film was a call for peace, a message which is both simple and complex. It was released at a time of fraught tensions between the government of then President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo and a faction of the Moro National Liberation Front loyal to its founder Nur Misuari. While it did not wade into this issue and development, “Bagong Buwan” tries to go back to the roots of the grievances of Moros, challenging stereotypes and convenient bifurcations.