In celebration of our 100+1 Essential Korean Films tribute, we revisit the most scandalous film of the 50s: “Madame Freedom” (1956) directed by Han Hyeong-mo. “Madame Freedom” was massively popular at the time of its release; in fact, it ranked as one of the most popular box office films of the decade. Small wonder, too. Just like the Hollywood melodrama, “Madame Freedom” parades the comfortable lives of the Seoul elite on-screen. As if celebrity could serve as a numbing salve to bloodshed, the silver screen's star presence soothed the fresh wounds from the civil war three years earlier.

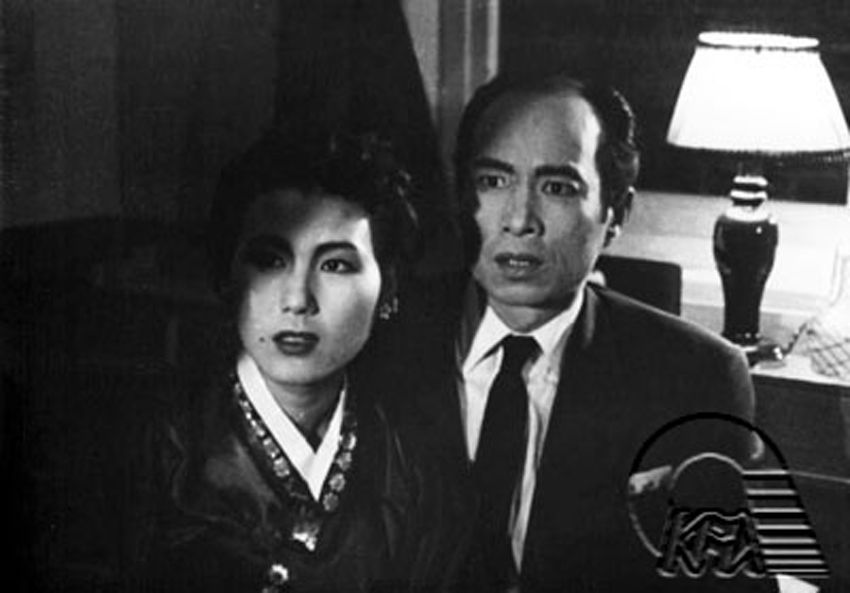

The overt salaciousness also drew audiences. Even by today's standards, “Madame Freedom” challenges moral boundaries. As the wife of the modest Professor Jang Tae-yoon (Park Am), Oh Seon-yeong (Kim Jeong-rim) starts off with a life of simple luxury. She dons luxurious hanbok and quietly raises her son, erstwhile her bejeweled friends drink alcohol and attend ballroom parties. Any sense of restraint, however, spins out of control when she begins to work at a Western boutique shop. Store owner Shin Chun-ho (Lee Min) makes advances towards her despite his marriage. At the same time, her flirtatious neighbor Choi Yun-ju (No Kyeong-hie) attempts to seduce her with jazz and dance. Amidst all this, Professor Jang merely looks the other way. During Madame Oh's nights out at the dance hall, he gladly entertains a young girl's unending flattery. As the adults go about their affairs, Professor Jang's home begins to fall apart. One fateful night, Madame Oh realizes she's indulged herself to a point of no return — but by then, it's much too late.

At first glance, Kim Jeong-rim's elegant stoicism seems off-putting. Though her stylized speech and movements capture the elegance of the upper class, they first seem awkward on film; she seems visibly uncomfortable even in her presumed everyday wear. However, as the film continues, Kim Jeong-rim visibly melts before the camera. Her stiffness translates into modesty, and her posture adopts a naturalistic bounce. Like a real lady brought down to moral havoc, her own body language unravels into that of a casual socialite.

The cinematic innovations found in “Madame Freedom” test not just ethical, but filmic propriety to the extremes. The first on-screen kiss of Korean cinema, for example, is by no means chaste. The camera swoops in on Han Hyeong-mo's custom crane, ready to capture Madame Oh's desperate intimacy up-close. After an hour and a half seeping in desire, even the act of adultery is more condoned than condemned. Indeed, like the network of taboo romance that eventually ensnares Madame Oh, each disloyal scene draws the viewer deeper into cahoots with her. In a twisted way, the film draws the viewer to cheer her blatant infidelity on. With this much emotional labor demanded from the viewer, it's little wonder that this film claims the title as the “Mother of K-Drama.”

Han Hyeong-mo's direction further accentuates the ambiguity on-screen in his masterful mimicry of the great Hollywood melodrama. Like Douglas Sirk, he carves up the mise-en-scene to indicate the characters' emotional bounds. Han does not simply copy without his own flair, however; these boundaries are aligned not with class, but on an East-West divide. The usually reserved Madame Oh, for one, bars herself off with coffee tables, countertops, and the sleeves of her elaborate hanbok. She only collapses into the arms of her lovers when they take her out for a spin in the dancehall — or in other words, when she succumbs to Western influence. Her wavering sense of self reflects that of Korean society. Like the rest of the country, she too capitulates to the imported culture of her military occupiers.

Madame Oh's vanity eventually leads to their destruction, however, or so Han Hyeong-mo warns. For each feast upon the wealthy's ostentatious lifestyle, Han Hyeong-mo adds a decaying complement. When the camera hungrily lingers over the dance hall's central mambo performer, her simpering smile recalls the hanbok-clad entertainer at Madame Oh's social club. This chanteuse warbles about innocent longing; the mambo dancer, on the other hand, silently tempts the gaze with her glittering frills. The doubles persist with each character in the film. Madame Oh's unapologetic outings clash with her husband's shamefaced secrecy; her steadfast lover overrides her flighty neighbor; and of course, with her traditional-to-modern wardrobe changes reflect Madame Oh's own changing chastity as well. In a strictly binary world where Korean is good and West is bad, Han Hyeong-mo argues that the latter could only corrupt the former. Through each character, he skillfully sets up a circle of mirrors that ultimately reveal the upper class's vanitas as much as their vanity. In this Korean society, Western pleasure is a fun, but futile pursuit.

While these conclusions may seem grave and perhaps even heavy-handed, “Madame Freedom” is still a great pleasure to watch. Like any K-drama, the narrative duly performs its duty to shock the viewer with elements of surprise peppered throughout. The Korean Film Archive's most recent restoration is also incredibly clear and high quality; nuances in the grisaille exposure still remain delightfully intact. Overall, “Madame Freedom” is still as invigorating a watch today as it was back then.