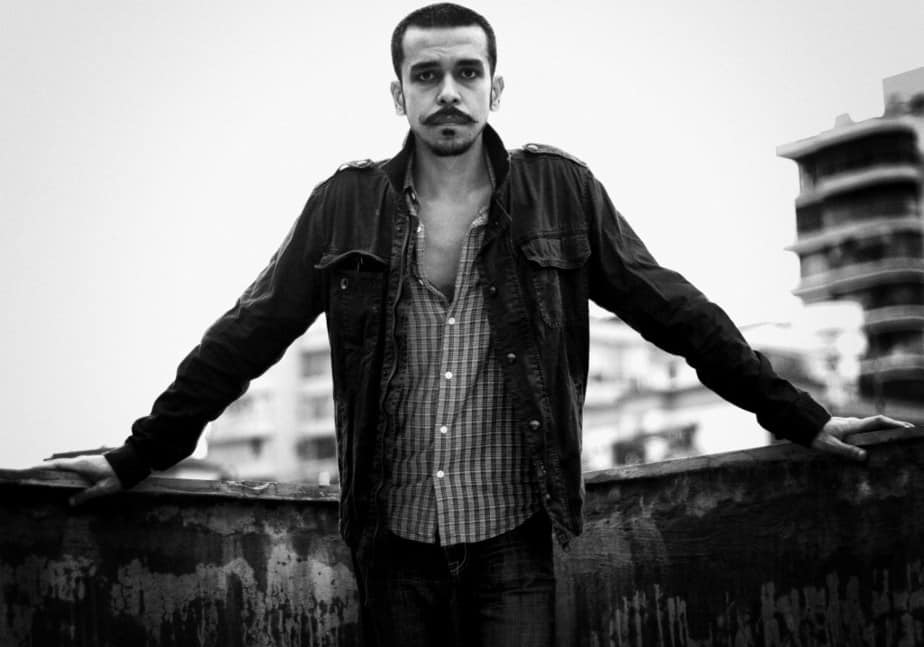

Taichi Kimura lives between two worlds. The Japanese filmmaker based in London made himself a name in the music industry by producing videos for Chemical Brothers, David Guetta, Chase & Status, and many more. Now, the 36-year-old director makes his debut on the big screen with his first feature „Afterglows“.

Director Taichi Kimura visited the Japannual Film Festival in Vienna for the international premiere of his debut film “Afterglows”. In our interview, the ambitious filmmaker reveals his vision for the Japanese film industry and gives personal insights into his career.

Let's start with the basics. Who are you? What's your background and what made you become a filmmaker?

I was born in Japan and I was raised in the middle of Tokyo. So, I was actually a city boy. I think the film that really got me was probably “Jurassic Park” (1993). I was like only five years old or something like that. The whole kind of film fascinated me and I wanted to go to America to make movies. Later, films like “Matrix” (1999) and Darren Aronofsky's “Pi” (1998) really struck me. At that time, I was having a difficult situation within the family, and film was a kind of escapism from reality. I wanted to get out of there and that's when I moved to the UK.

Although I dreamed of going to America, I went to the UK to become a film director. I couldn't speak English at all. My parents were really scared. I was always into football and I liked the vibe when I went there. So, I ended up in the UK and now I really appreciate it, because I love Europe, its people and culture.

I began studying film at university, but it was all theory and generally talk. It was not practical. After my graduation, my girlfriend broke up with me and I needed to get back on track. I didn't have any connections and applied for like 30 productions to get work for my visa, because it wasn't permanent. At that time I was partying a lot and had some DJ friends. So I was like “Let me just start filming you guys for free.” and I went on tour with them. That was my start as a filmmaker. It got bigger and bigger, and I ended up doing videos for the Chemical Brothers, Disclosure, and Fatboy Slim. My career started from doing these music videos and commercials. Three years ago, I felt like I was ready to do my first feature film.

So you always had this connection between music and film?

I was like really into music from the beginning. Thanks to my mom, who was always into Western culture. She was playing Jimi Hendrix in front of me. She was a huge inspiration and even took me to the cinema. She opened the door to these possibilities.

Any Japanese movies that inspired you in your childhood?

No, I was always into foreign stuff. Not many Japanese films at that time gave inspiration to our generation. There was anime, though. I'm still into Miyazaki, “Princess Mononoke”, and stuff like that. It's one of my biggest inspirations. But if I am honest, no live-action film really stood out to me. Later on, I started to like Japanese films a little bit more. For example, “Blue Spring” (1999) by Toshiaki Toyoda. I love it when the film gets a little edgy and has a kind of attitude. Then it's a great film.

In 2019 you did your first short movie, “MU”, which already has the same unique visual as “Afterglows”. Tell me about that short film project.

Takuma Hiramatsu produced it for me and I wasn't sure what I was going to do with it. I got the visual inspiration from the photographer Daido Moriyama. I wanted to turn his visions and subject matter into a modern film version.

What influence did Diado Moriyama have on you?

It was difficult for me to get inspired by Japanese film. Japanese photography had a big influence on me. Most of my inspiration comes from films outside of Japan.

I‘m from a documentary background and Moriyama‘s pictures are documentary. I love his pictures. There is no lie to it. As a photographer, he does not create a world, but he is invited and consumes it with a camera. His pictures and the works of Nobuyoshi Araki gave me a lot of inspiration. The whole experience of making my film was kind of reliving the experience that Daido Moriyama must have felt.

How difficult was it to recreate that style? Was it a lot of effort in the post-production?

No, no, no. It was mostly done on the set. We used filters. Nothing was post-production. It was all black and white from the beginning. We only adjusted a little bit of the brightness and contrast. That's it. When we filmed I was like “This is something special”.

How was the feedback?

We released it on the Boiler Room video platform “4:3” (Mu – 4:3 (boilerroom.tv) and it didn't have much feedback or anything like that. But somehow the only feedback I got was from Hiro Murai (“Atlanta”, 2016-2022), a guy that I really admire, who is from the music industry and also did the “This Is America” video for Childish Gambino. So, he was like “That's the best short I've ever seen”. That gave me confidence in doing a feature film version of it and six months after the release of “Mu” we started to work on “Afterglows”. It took me almost seven months to write the script and then we started shooting.

Tell me more about the shooting process. Did you have any approach in mind?

It needed to be in black and white, like Moriyama style. So it needed to be some kind of city because if you are shooting in the countryside there is no such vibe. You see, there were like a couple of rules I had from the beginning.

I wanted to use many locations. At the same time, I tried to hide the fact that we were on a low budget. That's why a city with the scale of Tokyo is perfect for that. You don't have many travel expenses. I also realised we could present this best with the figure of a taxi driver, who literally drives around. That was my first rule. The second rule was I wanted to follow just one character. I was really into “The Wrestler” (2008). I wanted to analyse the mental side of the character by focusing on the psyche of only one main protagonist. The last rule was the usage of voice-over. But I didn't want to do this kind of voice-over that you know from a Scorsese movie. Not this direct kind of thing. So I started to think about how to use this technique cleverly. We came up with the idea of the voice as a force coming from the radio. The radio is reading his voice and mind.

Those rules functioned as insurance for me. Since I felt like a rookie director compared to all those others, I knew it was not going to be perfect for me and I was scared. Once we had all the rules lined up we started to think about a precise storyline.

What was the idea behind the Doppelganger motive?

The whole feeling of the film is about obsession and how it can lead to isolation as well. I wanted to do a story about a man who is obsessed with something. I was looking back at my previous work and my wife is a big part of me. She supported me from the beginning. I am grateful for her being with me. I pictured what if she would be gone for no reason. I tried to put myself in the same situation as my main character.

Throughout my career, I was obsessed with becoming a film director and I realized that I've lost many friends because of that. Like Hayao Miyazaki said: “I don't like directing. Being a director means to lose friends.” Creating means that you sometimes have to sacrifice some emotions for it. You need to be tough, you need to be a bit harsh sometimes. Even though you don't want to. That's the obsession. So, I think obsession is an important emotion to drive people forward. I wanted to create a storyline along that.

You already had some screenings in Japan. How was the reaction so far?

The Japanese audience did not quite get the message. They were just shocked by how brutal my main character was. They didn't want to express their opinion about negative feelings, which led to controversial feedback. A large percentage of the Japanese audience lacks an understanding of film. Compared to the golden era of Japanese cinema, back in the times of Ozu, the audience had a better understanding of the dark side of the human being, and the films on screen also tried to express that. Today, the Japanese audience is not willing to accept these negative elements anymore. They only want to see happiness, cute girls, and stuff like that. I don't know what happened to be honest. It's just a different era now.

Are you disappointed with that?

No. At the screenings, I was surprised that a lot of youngsters came up to me and said that they liked the acceptance of the darkness within the human soul. So, I think a lot of the new generation in Japan is seeking a new art form. It's also weird that within the Japanese industry, there is a lot of praise for foreign films that have this edginess. But when it's shown in a Japanese film it is frowned upon.

You have a history with music in your career. How did you choose the music for “Afterglows”?

When I was partying in London, I met Thomas Yardley, who is a local techno producer. He is so talented and I asked him to do the soundtrack for my short “Mu”. It was amazing and so I naturally asked to do the score for my first feature, too. Considering that, partying is not that bad.

Music is also a key element in “Afterglows”. Like I said with cinematography a lot of Japanese movies do not care about music. They don't care about senses. Film is all about sensory perception. That's why I wanted the music to be very ambiant.

You had the chance of having the famous actress Megumi for your debut film. How did that come about?

It was funny. We had this cool, independent attitude that we wanted to pursue with our film and then our casting director called and said that Megumi, who is a huge actress, was interested in playing a part. Our first reaction was “Wow, that's amazing.”, but it was actually a bit contrary to our original approach to the project. I was surprised she had read the script because we didn't offer her anything. She just found it by herself and liked it. Now Megumi even produces my second movie.

Can you tell us more about this new project?

It is about my mother, who raised my older sister and me as a single parent in the 70s. Back then, Japan was even more male-dominated, but she was really tough. She had to sleep on the street and work for the Yakuza because she couldn't find a job. It is a mad story and the film will be based on her real life. I think my mother's story can be a huge inspiration to many people out there. Especially in times like now, where equality is a big thing, this could be the right moment to produce it.

Will you continue with that black-and-white style?

It won't be in the style of “Afterglows”, though. I don't want it to be a tragedy, but a hopeful portrayal of an independent woman. I want to focus my career as a director on social issues to inspire society.

That's the one thing I want to be known for. The other is a distinctive style. In Japanese cinema, there are so many great storylines, but they ruin it with cinematography. They don't understand the medium of film. You consume mostly with your eyes, which makes the visual aspect so important. There are many great aspects of the Japanese film industry (acting, marketing, etc.), but the visuals are pretty flat. If you use the potential of cinematography in the right way you can double or triple the emotional impact of your movie.

Were there some things you had to consider when you were shooting in black and white? In contrast to shooting in color?

It made me focus on the understanding of the story. Because another big thing in the film is the two sides. Man and woman. Right and wrong. Justice and injustice. There is the theme of dualism. The black and white made sense for me to underline this. When I was shooting, I was constantly thinking about how to keep the balance between these factors.

One of the most fascinating scenes was the opening scene in the bathtub. The black-and-white contrast was very surreal at this moment. When blood runs into the water, it feels like Sayumi‘s death wasn't real and it sets the tone for the whole movie. So for me, this was a premise on how to understand your film. That this is fiction and out of touch with our reality. But rather a distorted version of reality or dream that turns more and more into a nightmare.

I think throughout the film there is the question of whether that is real or not. Is the suicide real? Is the voice-over real? I made the film very vague and did not want to give one clear answer for certain sequences. I wanted the audience to have their own space to understand and analyze it within themselves. That's why many moments make you question reality. I like a lot of action and I wanted to have that for my film as well. The violence and gore escalate towards the end. I used this escalation to entertain the audience.

Speaking of the audience, in this day and age, people have a very short attention span. How to keep the attention span of the viewer?

When it comes to the rules of filmmaking, I think, there are always certain trends. Look at “Oppenheimer” it is a long movie, but still people loved it. Japanese movies tend to be too long and there is not much happening. You could shorten them up to one hour and a half. The subject of these movies and the pacing do not match. On that matter, the Japanese film industry is still in the process of learning.

Do you wish for a more Westernised film industry in Japan?

Absolutely, 100 percent. I want them to do their own thing, but they need to understand that they have to appeal to foreign audiences as well. It's an easy thing to understand. If I open a restaurant I want also everybody to come to my place, not just a few local people.

Back in the day, there was more anarchy in the Japanese industry. Nowadays it's much more conservative. Look for example at Korea. They apply their pacing to Western habits but still show off their culture. If Korea can do it, Japan can do it easily. It is just a matter of mentality.

I don't think that Japan needs to be Westernised. Japanese film doesn't have to be Westernised. The industry just needs to understand the global scale of art and develop the will to show it to everyone in the world. Japan has amazing subjects, a great history, and culture. Every time I go there, I am overwhelmed and want to put it into a film. But Japanese people are not interested in it. Then these foreign directors come and think it's cool and turn it into a movie. Like Wim Wenders did with „Perfect Days“ and there you go, Oscar nomination. You need someone from outside to hint at these things.

There are a lot of car scenes in your movie. Did you shoot a lot on location or studio? Was it difficult to get permission to shoot?

We shot all on location but without any permission. We had a tiny camera that we already used for “Mu”. We also tried all kinds of different models, but in the end, the tiny one was the only one that was able to create the gritty look.

“Afterglows” was done undercover, guerilla style?

Yeah, when someone approached us, for example at Tokyo Station where they are strict, I just said we are shooting for a wedding or something. The only time we had to get a permit was the killing scene on the street. We tried it once without, but they stopped us and we had to get legal papers. We were also moving around a lot, with the cab scenes and everything. It was helpful because it didn't attract too much attention.

Do you want to continue shooting movies in Japan or are there any other countries that are on your bucket list?

I will shoot my third film in the UK. Eventually, I will slowly move my productions more into Europe. But I will also always come back to Japan, because that's where I'm from originally. I absolutely love the culture and I can see so much potential within the Japanese film industry.

I want to be that Japanese director with a Western vision and produce something on a global scale. Culturally, Japan is very consumed by Hollywood. There are a lot of Western movies that portray Japan in the wrong way, too. Japan needs to be protected from these bad movies and I think Westernised filmmakers like myself can jump in there and make a kind of statement and show a different view.

When shooting “Afterglows” I wasn't aiming to do a commercially successful movie. But now with my next projects, I want to make a living out of it. Directors tend to be super selfish, but I try to keep the audience in mind, too.

Is there some hope for the Japanese film industry?

Of course, there are some great filmmakers now. For example Anshul Chauhan. You need someone like him from the outside, who appreciates and respects Japanese culture.

I feel like, in their doing, a lot of Japanese directors only aim for a broader perspective in matters of film festivals like Cannes. That produces always the same subjects. I want more diversity and have those big budget productions to be seen outside of Japan, not only arthouse festival movies. I am aiming in that direction. I want to combine social issues with an entertainment aspect.

Thank you very much!