Essentially split in two by the Korean War, the cinematic 50s of the country focused mostly on two themes, the liberation from the Japanese Occupation Forces and melodramas about the, highly influenced by the US, life in the country after the war. The financial progress, which was actually instigated by the war, had a number of repercussions on society, with a plethora of people getting richer, but also leaving the ones who could not keep up in the margins, a concept that became the base for many melodramas. Also of note is the fact that women had protagonist roles quite frequently, with a number of “heroines” who went against the blights of Confucianism, being the medium for intense social commentary. Lastly, the production values increased significantly, to the point that a number of titles look good visually, even to this day. Here are ten of the best among them, in chronological order.

The links below each listing lead to the YouTube channel of the Korean Film Archive, where all the movies here can be watched for free.

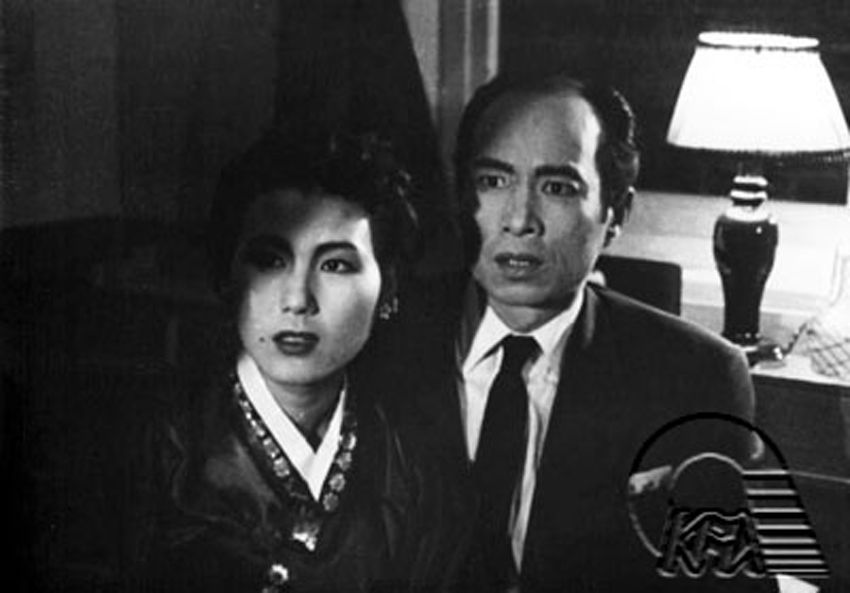

1. Hand of Destiny (Han Hyeong-mo, 1954)

One of the most interesting features in “The Hand of Destiny” is perhaps how the idea of identity unfolds within the narrative. Whereas the first part progresses like a somewhat corny romance, the revelation of the characters' true identities, their motives and essentially the conflict as a result of that, also comes as quite a surprise to the viewer. Similar to works from film noir, the notion that people and the world are not what they seem to be constitutes the foundation of Kim Seong-min's script. Security turn into paranoia, fear and uncertainty as the real instances of power and influence, symbolized by the recurring image of the hand of Jung-ae's superior, who is never seen in full until the very last moments of the film, are uncovered. (Rouven Linnarz)

2. The Widow (Lee Bo-ra, 1955)

Park Nam-ok presents a rather invigorating story, which, finally, presents women in the urban setting as in charge of their own fate and not just the recipients and/or carriers of tragedy for them and their families when they decide not to follow the rules of Confucianism. In Park's world on the contrary, the women are those who manipulate the weaves of fate, with the men, in essence, being puppets to their will.

3. The Youth (Shin Sang-ok, 1955)

The movie thrives on its individual moments. The action scenes are impeccably choreographed and brutally realistic, with the initial one, the one with the dogs and the finale one being particularly memorable, also because the “good guys” actually tend to lose in them. These scenes also showcase the excellent job done in both Yang Bo-hwan's cinematography and Kim Deok-jin's editing, that find their apogee in the action scenes. The relatively fast pace of the latter, also suits the aesthetics of the movie nicely, adding to the entertainment it offers. Excellent job has also been done to the art direction by Choe Gyeong-sun, and the costumes, with the overall presentation of the era being impressive. Kim Dong-jin's music on the other hand, particularly during the action scenes, seems completely out of place, essentially faulting the overall visual aspect in these sequences.

4. Piagol (Lee Kang-cheon, 1955)

The public and the authorities may have criticized the film for the humanization of the North Korean partisans, but seen in retrospective, the film is anything but pro-communist. The members of the band are portrayed as filled with faults, both as human beings and as soldiers. The love triangle (and the addition of So-joo) is probably the harshest element in that regard, particularly since General Agari is presented as a true satyr, a man who uses his authority to have sex, with the fact that he is eventually turned down by Cheol-soo being another “nail in his coffin”. Agari is actually the main source of anti-communist propaganda, since he is portrayed as overly proud, cruel, completely unforgiving, having almost no control over his troops apart from when he kills them, and in essence of being the only one who does not understand the situation. The fact that Ae-ran is portrayed as smarter, more down-to-earth and in essence more loyal, could also be perceived as a kind of mocking towards him. (Panos Kotzathanasis)

5. Madame Freedom (Han Hyeong-mo, 1956)

The cinematic innovations found in “Madame Freedom” test not just ethical, but filmic propriety to the extremes. The first on-screen kiss of Korean cinema, for example, is by no means chaste. The camera swoops in on Han Hyeong-mo's custom crane, ready to capture Madame Oh's desperate intimacy up-close. After an hour and a half seeping in desire, even the act of adultery is more condoned than condemned. Indeed, like the network of taboo romance that eventually ensnares Madame Oh, each disloyal scene draws the viewer deeper into cahoots with her. In a twisted way, the film draws the viewer to cheer her blatant infidelity on. With this much emotional labor demanded from the viewer, it's little wonder that this film claims the title as the “Mother of K-Drama.” (Grace Han)

6. Hyperbolae of Youth (Kim So-dong, 1956)

Han Myeong-mo directs a situational comedy, drawing much laughter from both Boo-nam's inability to do, well, anything and Myeong-ho's awe but also looking down on the lives of the rich. This aspect, along with the musical and the romance are responsible for the entertainment the film offers, and actually carry it from beginning to end. In that regard, the movie benefits the most by the acting, with both Hwang Hae as Myeong-ho and Yang Hun as Boo-nam giving excellent performances, which also benefit by their actual appearance. The way the romances progress are quite enjoyable to watch, and also benefit by the performances of Ji Hak-ja as Jeong-ok and Lee Bin-hwa as Mi-ja, whose metastrophe in the way they end up liking their new “guests” is one of the best parts of the narrative.

7. The Flower in Hell (Shin Sang-ok, 1958)

So despite the rather questionable buildup in places, “The Flower in Hell” is potent and mostly progressive early South Korean cinema that manages respectably level-headed examination of the society's outcasts. Furthermore, it serves as a fascinating progenitor of the genre-meshing trends that the industry would become known for worldwide today. (Wally Adams)

8. Forever With You (Park Seong-ho, 1958)

Yu Hyun-mok manages to make a number of sociopolitical comments. The financial situation of the poor, who had no way out of their poverty during the time (after the Korean War that is), is the first and most obvious, at least partially justifying Gwang-pil's actions. The penetration of western culture in all parts of Korean society is another central one, with the music, drinks and way people dress as exemplified in the hostess club highlighting the fact as much as the way Christianity has changed Sang-moon. The third one, and somewhat more subtle, is presented through Ae-ran, who finds herself in the middle of the struggle of two men, without having any choice in the matter, although her feelings are quite clear from the beginning, as much as her faith in the constitution of marriage. The fact that she is bedridden for almost the whole duration of the main timeline also functions as a metaphor for her situation. On another note, the final revelation of the child's father also seems to refer to the divine justice both her and Gwang-pil seem to suffer due to having extra-marital relations, with the fact that she has the worse fate presenting another comment about the role of women in the then society. Do Kum-bong in the part highlights all the aforementioned elements quite fittingly.

9. Nameless Stars (Choi Keum-dong, 1959)

What is impressive though, is that Kim Gang-yun's effort results in a true epic, particularly through a number of scenes that feature scores of actors clashing between them with sticks and bare hands. These sequences are quite impressive, starting with the baseball fight one, continuing to a number of others both inside the school and outside, and concluding with the final one against the authorities, where the participation of both boys and girls results in a truly extravagant spectacle. Their loud voices become the soundtrack of the title, while these sequences also highlight Kim's ability to direct many actors together on screen, DP Kim Hyung-keun's ability to capture them in the most graphic and impressive fashion, and editor Yu Jae-won to connect them in a way that retains continuity but also induces the film with an uncanny pace. At the same time, a number of them are set in a way much similar to westerns, an element that adds even more to their presentation.

10. A Female Boss (Han Hyeong-mo, 1959)

The Hollywood aesthetics, as already mentioned, are everywhere to be found. The way the people dress, the music they listen to, even the way they conduct themselves occasionally speaking in English and having adopted western names all point towards this concept, as much as the scenes in night clubs where mambo and cha-cha seem to dominate, while the customers are drinking beer. Furthermore, a rather lengthy scene of a basketball game where Yong-ho proves the ” hero ” of his team and the rest of the office's crew cheer him could easily be found in any American movie. Lastly, the way women and particularly Yoanna conduct themselves, definitely points towards western society values regarding the emancipation of women.